Neither the Northeast or the North End

BY: Mark Spano

Memory…belongs to the same part of the soul as imagination; it’s a collection of mental pictures from sense impressions but with a time element added, for the mental images of memory are not from perception of things present but of things past. —Frances Yates from The Art of Memory

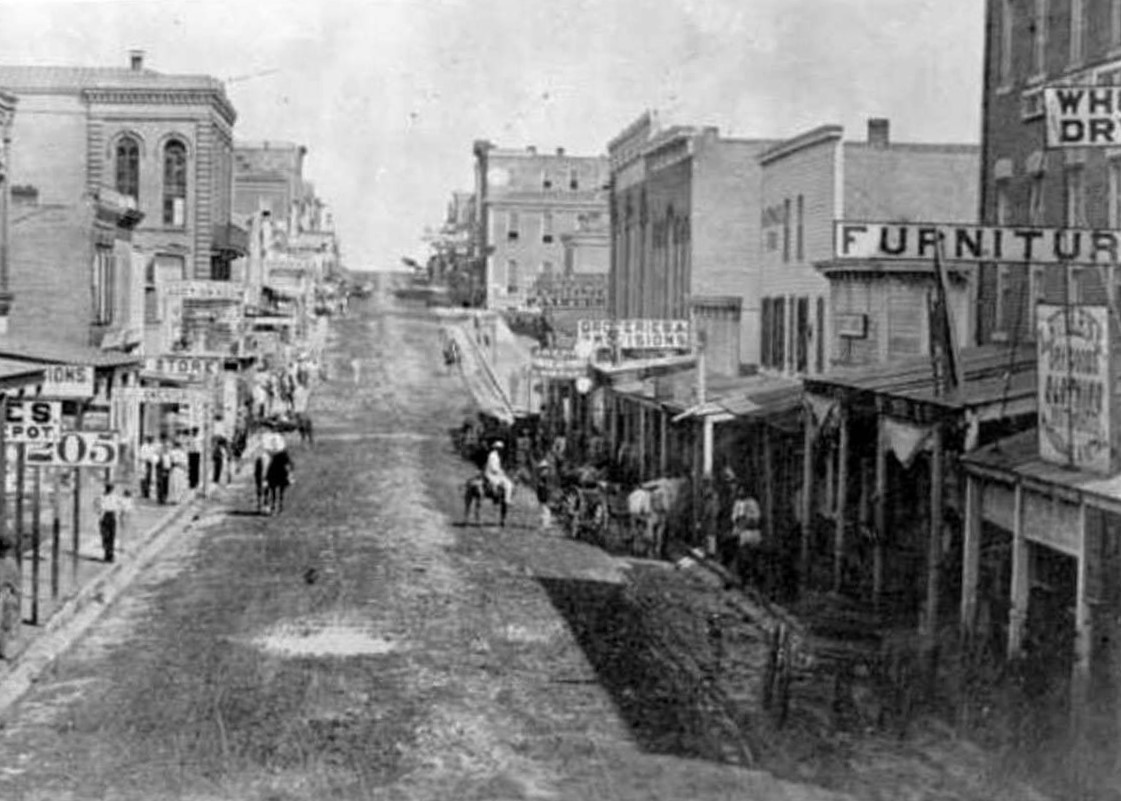

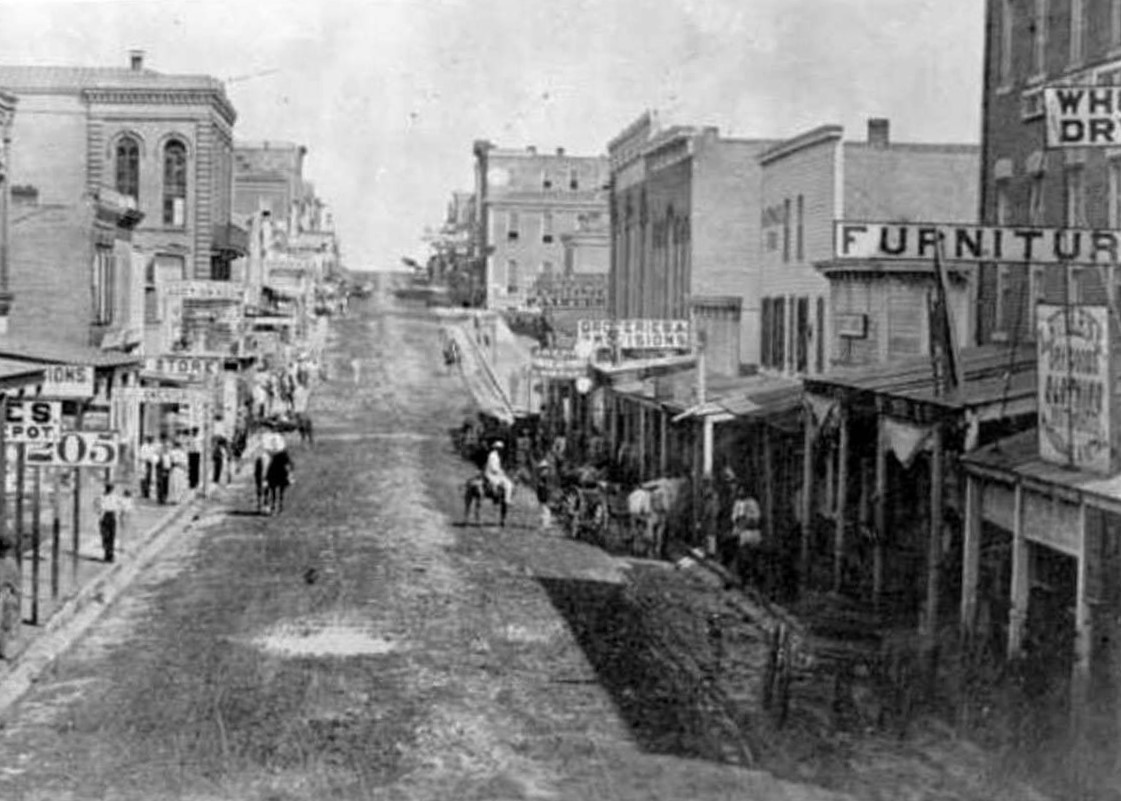

I grew up in a curious little locale hidden away on the north side of Kansas City, Missouri. The North End was west of us, and it was where the earliest arrivals from southern Italy and Sicily settled in what was called, then, the Town of Kansas. The city’s earliest founders rejected such possible names as Port Fonda, Rabbitville, and Possum Trot. The town was founded in the 1830s as a port at the confluence of the Missouri River and, what was called at that time the Kaw River.

My father’s family settled in the North End in the 1890s. It was the river market district. The Spano/Inzerillo side of my family was from the Vucciria market in Palermo. My grandpa Spano entered the United States through the port of New Orleans. He moved to a place that had much in common with the Palermo market In Kansas City he continued in the produce business, the same work he had done in the old country.

On Saturdays in the 1950s, my father used to take my brother and me to the City market. We bought produce, bread from S&A Bakery, and Italian Sausage from Scimeca’s. We stopped by to see our cousins who still had businesses in the market. I remember vividly my cousin Connie. (That’s a male cousin: Connie being a diminutive for Constantino.) Connie weighed pretty close to four hundred pounds.

"You wanna banana, Bay?” He bellowed at me in a voice like an artillery round. Italian people in Kansas City used the expression, “Bay” like it was the term “Babe” or “Baby” or maybe even “Beddu.” No one has ever explained to me convincingly the origin of the expression. Cousin Connie worked hard but never seemed to have much money due to a formidable gambling habit.

The North End was the early tenement neighborhood and the Northeast was a leafy old residential area where Italians moved when they had enough money to buy a house and leave the tenement. Our neighborhood was halfway between the two located about ten blocks south of the Missouri River. To the east, in what was called "The East Bottoms," were grain elevators, agricultural chemical plants, and railroad yards. To the west, just beyond "downtown" and the North End were the stockyards and packing houses in what was, imaginatively enough, called "The West Bottoms."

The Northeast was a leafy section of town on a bluff above the Missouri River. The Northeast had boulevards, parks, and numerous old mansions that had belonged to the earliest city founders. The Northeast was where you moved when you no longer had to live in the tenements of the North End. Italians could not really move to other parts of the city or else their prosperity would never be seen by their fellow Italian-Americans, and to be prosperous is to be observed as prosperous by those on the rungs just below you in the social hierarchy.

Our neighborhood was a no man’s land about halfway between the North End and the Northeast. It was zoned both industrial and residential. This was a variant of mixed-use you rarely see today in America. Factories and warehouses stood alongside apartment houses and shabby bungalows.

On a summer night, given the direction of the prevailing wind, there were always smells. From the west, one night, we could be ingesting the dusty sick stench of cattle and pig manure coming from the stockyards. A night later, the packing houses might be emitting the sweet rank simmering of meat by-products in the process of becoming bologna or canned chili. From the east, there were insecticides, fertilizers, and a pollen-like fog that came off the wheat pouring from the grain elevators to train cars.

These local industries of our mixed-use neighborhood required trucks and trains to do business. At every hour of the day and night, eighteen-wheelers rolled up and down Chestnut. (We called our street "Chestnut" not "Chestnut Street." This is how Kansas Citians talk.) The charcoal-colored dust from diesel exhaust covered everything, indoors and out. My mother could never stay ahead of the dusting in our apartment.

Outside, you could almost always write your name in the grime accumulated on the parked cars. There was constant noise. No place was quiet. In the deep of the night, railroad cars were assembled into long freight trains. Only blocks from my bed, freight cars crashed into one another in a nightly thunder that I nearly grew to require in order to fall asleep.

The five of us, my parents, my sister, my brother, and I lived in a four room apartment in about the same living space as double garage. We were on the first floor of a four-unit, turn-of-the-twentieth-century building. When the wind blew or when the trucks rumbled past, the windows shook in their dry rotted frames. Our apartment was located directly over the boiler for both hot water and radiator heat. We had no air conditioning. Winter and summer, our apartment was hot.

We lived in St. Aloysius parish. Many of the old people at St. Aloysius were Irish. The Irish were the original holders of the neighborhood. But, unlike the Italians who moved to the Northeast and north of the Missouri River out of the old neighborhood, the Irish who had "made it" moved south in the city. They followed the Jesuits who had founded St. Aloysius but had left St. Al ’s for the greener pastures of a prospering south Kansas City upper middle class. Having been educated by some of those very Jesuits, I later grew to realize that the Jesuits knew a deal when they saw one, and the waning fortune of crumbling St. Al’s was no deal.

A few Italian families, like my own, remained in the neighborhood, somehow stalled in the anxiously awaited ascent into the middle class. The remainder of the neighborhood was grudgingly shared by Mexicans, Blacks, and "peckerwoods." Peckerwoods were people from the country, Southern Missouri, Arkansas, and Oklahoma. They mostly drove trucks even when their jobs did not require the ownership of a truck. They also listened to "hillbilly" music. This fact alone served as irrefutable evidence that peckerwoods lacked aspirations to a better kind of life. Few peckerwoods had ever lived in the city before their arrival at the tired old brick and stone apartments lining the west side of Chestnut. Fewer still had ever resided in structures that touched adjoining residences at the top, bottom or opposing sides.

On a Friday summer evening, as most of our neighbors watched from their porches, two tattooed country boys whaled the tar out of each other over not much more than having drunk too much of their paychecks. As their wives drug them inside ending the evening's entertainment, I overheard old Mr. Fero say, "You know, you just can't stack peckerwoods."

But, their unstackability or truck-driving or "hillbilly" music or their ignorance in the ways of tenement living paled to the true offense of merely being a peckerwood. Peckerwoods were not Catholic, therefore, cultureless in the eyes of the arbiters of such things in my neighborhood. Clearly, there was a hierarchy at work here. Italians were the best because we were Italian. There was little or no argument on this point.

The Irish could be tolerated for after all they were Catholic as we were, and they aspired to some semblance of respectability. In fact, the Irish aspired to a good deal more respectability than the Italians in my neighborhood, but this was observed by my mother and her gaggle of canasta-playing neighbor ladies as social pretense.

The Mexicans were Catholics, but their respectability quotient was quite low by neighborhood standards. Their looks and possessions never glistened with the glamour that was requisite to Italians. This branded Mexican Americans with comments like, "They're God-fearing people," meaning, "They may believe like us, but they sure aren't blessed like us."

Blacks were respected though not totally included. The Italian boys respected black boys because of their toughness. Everyone of us knew that T.C. could throw further and fight harder. T.C. was clever with building things like go-carts and skateboards. He had physical prowess and strength. This was serious capital with neighborhood boys. Italian girls and women had no commerce whatsoever with Black people. It was an unwritten rule.

Orientation within Kansas City was based on the parish. It is how Catholics divided the city. The parish existed as a geographical unit just higher on the scale than the neighborhood. I learned later that Kansas City's old-time political boss, Tom Pendergast brought in the vote in our town parish by parish rather than by ward.

As I said, my family lived in St. Aloysius Parish. We were part of a ragtag mix of city dwellers who gathered on Sundays and holidays in a seventy-year-old Catholic church. The interior of St. Aloysius church suffered under the most sentimentally ornate decor, while the building itself barely survived in a state of post-blitzkrieg dilapidation. Each group that had passed through our neighborhood on that great journey to prosperity left some lasting and tasteless mark of new-gotten gains on the sad old church.

Nostalgic departing parishioners seemed always to endow St. Aloysius with gifts of dying Jesuses bloodied beyond the observability of the faint-hearted or infant Jesuses or Blessed Mothers draped, beaded and brocaded like Las Vegas showgirls. Never did these warm-hearted departing St. Aloysiusians offer a cash gift to repair boarded-over stained glass, giant doors dropping off hinges, falling plaster, or decades of accumulated pigeon droppings mounting into new spires on the church’s exterior. The St. Aloysius church building was a mess that might best be described as Western Missouri 1880’s Irish Italian Gothic Baroque Rococo.

Just down the street, not far from Saint Aloysius parish school, Italian people owned a small grocery store. They were not Catholic. Mr. Goia called them, “Mancinu,” meaning, “left-handed” or “sinestra.” They were the only Italian family we knew who were not Catholics. An aging mother and grown son and daughter ran the place. An old-timey photograph in plaster gold-painted frame of the long-departed Papa hung above the front counter. This family clearly had some disdain for the rabble of southern Italian Catholic school children who at lunchtime overran their store to buy penny candy.

All of the Italian families were from the south: Naples, Calabria, Puglia, Sicily. And, in the middle of the United States, just as in Italy, the South meant south of where your family was from. A few Lebanese families were granted free passes as honorary Italians. As neighbor children, we were like siblings living in separate apartments. Every parent in many cases functioned as the parent of all. Some number of us were not just neighbors but cousins. Most of us had relatives living within walking distance. Frequently, we all played together. We ran around like a horde of demons believing we owned the world we inhabited.

Husbands and wives both worked unless the husband gambled for a living. There were a few of those. Young people by fifteen or sixteen had some kind of work. Mothers smoked, played cards, and drank coffee.The men listened to sports on the radio.

In the early ‘60s, we listened to race music on KPRS in Kansas City, and at night when reception was good, we listened to more rhythm and blues broadcasting from KOKY out of Little Rock, Arkansas. We loved Bobby “Blue” Bland, Little Esther, James Brown, Little Milton, and Albert King.

We went to CYO dances. The girls teased their hair and wore more than ample eye makeup. In those years coral lipstick was popular. It muted their lip color to that of a corpse. We danced like Blacks. On Sunday afternoons we went to the Vista Show where the boys and girls necked. Many of these couples went on to marry. They are now grandparents.

When I went across town to a Jesuit boy’s prep school, my classmates listened to hard rock and folk music. I was raised on a strict diet of R&B, Soul, and Doo Wops. I dressed differently and liked different music. I was an alien.

Most parents may have paid some lip service to the tenets of right living, but as children, we understood that in their hearts grown-ups really knew what counted. In our dull world of school, church, and hanging out, and in our parents' even duller world of mindless physical labor, lousy living conditions, and the unending joys of child rearing, what counted was glamour. Glamour was the cause, the cure, the ultimate escape from the heavy boredom of our lives in a place that offered little else but cheap rent.

None of us knew enough of the world beyond our neighborhood to want to be lawyers or doctors or President of the United States. Few of us had met any lawyers or doctors. The ones we might have known didn't live where we lived, and the president existed only on television, no more real than Ward Cleaver. The grown-ups we knew worked in factories, tended bar, or drove trucks. Work was boring. Everyone knew that. We wanted to be Doo-Wop singers or prize fighters. We wanted cars with leather seat covers and gold watches. We wanted what the men called one another on the street as if it were a name. We wanted "Easy Money."

There were, of course, those who didn't work. Most of them gambled. Gambling as a career choice was not considered by my neighbors as a "true" involvement in crime and, was, therefore, tolerated. Other rackets, such as prostitution and drugs, might not have been.

Buying stolen merchandise was a crime. My father would have killed us if we had done such a thing. But, other of our neighbors possessed little of my father's iron on matters of honesty, and a bargain, after all, was a bargain. Few of us probed deeply as from where such bargains came.

Organized crime was given from my earliest memories. And, as I said, few considered gambling much of a crime, but we saw and heard about far more serious criminal activities. That said, most of the people who lived in our tired little quadrant of the city were law-abiding and hardworking, if not always the best-informed citizens. Gossip regarding local crime was recurrent, because we were bored. Our blue-collar enclave was low-rent, relatively safe, somewhat remote from the rest of the city, drab, and unmitigatedly dull.

The parish sponsored spaghetti dinners and ice cream socials. It was local legend that Mrs. Dana made the best pizza at the ice cream socials. Her slices sold out first.

Mr. Licata was an ancient widower who showed up at every parish function. He was a sharp dresser, especially for a man in his late eighties. He was an usher at Mass and always passed the collection basket. In the early years of his life, he was a hood and provided muscle for local gangsters. After the death of his wife, he got religion and became the pillar of our parish.

With high school, college, marriages, and deaths, we were all pulled in different directions from the neighborhood. As an undergraduate on the East Coast, my Italian-American classmates from New York and New Jersey did not believe that I grew up in an Italian neighborhood in the very center of the United States.

Of course, we all go back to the old neighborhood. Few of our haunts remain. But of course we have all matriculated to corporate jobs, to ritzy suburbs, and to country clubs to which our grandparents would have never been allowed membership. Today there is a yearly Italian Festa north of the river. Many of the ancestors of the old communities come out for the event. You may also see the well-heeled children and grandchildren and great grandchildren of the biggest mobsters posturing to one another that their extraordinarily visible signs of affluence did not come from ill-gotten gains.

We understood that we would all move on from the neighborhood one way or another. What we did not understand what we could not have ever understood was that neighborhood life, with all of its challenges and all its flaws, gave an experience of food, family, and the closeness of truly beloved neighbors. We could never have imagined that matriculating up the social ladder would cost us community as we had once lived it in this neighborhood that was not the North End or the Northeast.

You may be interested

-

“The Hill” St. Louis’ Little Italy

When the fire hydrants begin to look like Italian flags with green, red and white stripes,...

-

'Genealogy Roadshow' enters second season on...

"Genealogy Roadshow" returns Jan. 13 for its second season on PBS, and it will feature a g...

-

'I've enjoyed every moment' - USMNT's Gianluc...

Busio moved to Venezia in August 2021, with the club breaking its own transfer record to s...

-

'Impractical Jokers' comedian coming to Sprin...

One of the original "Impractical Jokers" will stop at Springfield's historic Gillioz Theat...

-

'St. Louis Square Off' Vows to Determine the...

If your dream pizza comes with a cracker-thin crust, a mound of gooey Provel and, yes, squ...

-

‘Boy, did I dream big with the sandwiches!’ |...

If there would ever be a Walk of Fame down the streets of The Hill, you can bet Marjorie A...

-

‘Call it the broken table’: Big Belly’s Itali...

A hot meal and warm place to rest are that much more important as Kansas City, Missouri, c...

-

‘It’s time’: ‘Viviano Variety Show’ to have o...

For 37 years, the annual “Viviano Variety Show” benefit has operated by the theatrical cre...