How many times have you looked at Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper? It’s one of the most studied and admired works of art in history. But there’s a detail that most people miss. Right at the center of the table, beneath the hands of Christ and his disciples, lies a white tablecloth adorned with delicate geometric patterns.

While it might seem like a simple decorative touch, that cloth actually holds centuries of Italian heritage. It’s a reflection of a rich textile tradition from Umbria dating back to the 14th century—the famous tovaglie perugine, or “Perugian tablecloths,” recognizable by their blue diamond motifs woven into a white linen background.

Far from being a relic of the past, this unique craft still lives on today in Umbria. Master weavers continue to handcraft these textiles using the same medieval techniques, blending linen and cotton on traditional looms. Think about it—Leonardo chose to represent this very fabric in what is arguably the world’s most iconic painting, offering a subtle tribute to the artistry of his homeland. And seven centuries later, that same craftsmanship is still practiced by skilled artisans.

Textile production in Umbria dates back to at least the 12th century. It was heavily influenced by French traditions, especially by the weavers of Lille and the teachings of Giacomo Bergierès. Over time, Perugia developed its own distinctive style, creating fabrics like the tovaglie perugine, typically woven in a “partridge-eye” pattern in white linen with indigo cotton bands. These fabrics were used both in churches and noble households, and you can still see them depicted in numerous medieval and Renaissance paintings housed in churches and museums throughout Umbria.

The patterns often feature stylized flora, fauna, and abstract geometric designs, sometimes even inscriptions or blessings. Their aesthetic owes much to Middle Eastern influence, which filtered into Italy through centuries of trade. By the 1800s and early 1900s, interest in traditional textile work was revived through the use of hand-powered Jacquard looms, leading to a rebirth of artisanal weaving in the region.

In different towns across Umbria, local styles flourished. Perugia produced a flame-patterned fabric known as fiamma di Perugia. In Assisi and Città di Castello, the Renaissance-style “double cross stitch” known as Punto Assisi came back into favor. On Isola Maggiore in Lake Trasimeno and at the Ars Panicalensis workshop, Irish crochet lace—known locally as pizzo d’Irlanda—made a comeback. Orvieto, meanwhile, gained international renown for its exquisite Ars Wetana lace, another intricate Irish-inspired tradition.

The 14th and 15th centuries marked the golden age of the tovaglie perugine. These table linens were made with a partridge-eye weave of white linen and decorated with indigo-dyed cotton, often sourced from the guado plant, also known as woad. The blue patterns, usually confined to horizontal bands at the ends of the cloth, were thought to resemble the movement of waves, and in Perugian dialect, the stylized design was affectionately called “belige,” referencing the rocking motion of the loom pedals used during weaving.

Originally used as altar cloths in medieval churches, these textiles quickly gained popularity among the aristocracy. By the 15th century, they were considered luxury items and were found throughout central Italy, from Tuscany to the Marches, and even as far as northern Europe—Trentino, Friuli, Carnia, and Sicily. There, educated and elite buyers adopted them as a symbol of social status. The cloths became prized components of dowries and were later repurposed into curtains, cushion covers, shawls, or even headscarves. In more practical settings, they were rolled up to support baskets carried on women’s heads, or worn as belts, bags, banners, or tournament prizes.

Today, traditional Umbrian weaving is still part of the region’s cultural and economic identity. Several family-run workshops continue to use 18th- and 19th-century foot-powered looms to create textiles in the same way they’ve been made for hundreds of years. The patterns—ranging from stylized humans and animals to good-luck phrases—are carefully woven with supplemental weft threads in cotton or linen blends. The blue bands alternating with ivory ones remain the signature of this historic fabric. Every piece is handmade, and crafting a single tablecloth can take up to 20 days.

Leonardo’s Last Supper might be the most famous example, but these tablecloths appear in numerous works of art. Late medieval and Renaissance painters often included them in depictions of the Last Supper, alongside other fine textiles like silk from Lucca, Sicily, or the Far East—fabrics reserved for churches and royal garments. One example is a painting by the Maestro delle Palazze, dated to the late 13th century and now housed at the Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts, which shows a long table draped with a classic Perugian cloth. Giotto immortalized them in his fresco The Dinner at the House of the Knight of Celano, part of the vast cycle of the Life of St. Francis in the Basilica of Assisi. Other noteworthy appearances include Pinturicchio’s frescoes in the Baglioni Chapel in Spello, and the Last Supper by Perugino in Foligno.

Through all these examples, the tovaglie perugine have woven their way into art, history, and daily life—enduring symbols of Umbria’s extraordinary textile legacy.

You may be interested

-

'Fairytale' Italian village loved by celebrit...

Nestled in the heart of Italy's Umbria is a village that is often referred to as being amo...

-

'In the US you could never do this': How an A...

When life hands you grapes, you make wine. Writer John Henderson meets a Californian-Sicil...

-

'Mechanic' of music Da Vinci's organ reconstr...

No one had ever heard its "voice" before: a warm, ancient sound similar to that of a flute...

-

'Mona Lisa's' identity could be revealed thro...

By Jamie Wetherbe The mystery of "Mona Lisa's" real-life muse, which has spawned centurie...

-

'Stanley Tucci: Searching for Italy': What's...

Umbria is "the green heart of Italy. Not a jealous heart, but a fertile one," Stanley Tucc...

-

'Truffle tourism' worth 63 million euros in I...

Truffle fairs and truffle hunting tours have attracted some 120,000 visitors to Italy this...

-

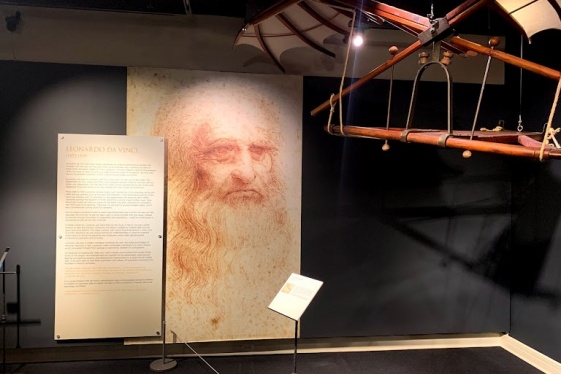

'We have Leonardo's among us': DaVinci exhibi...

A global exhibit showcasing newly-built works based mostly on the sketches of Leonardo DaV...

-

‘Da Vinci & Michelangelo’ return to Manatee P...

“Da Vinci & Michelangelo: The Titans Experience”: 7:30 p.m. Dec. 28, 8 p.m. Dec. 29 and 2...