One of the most important and powerful fields of the American society, what we can generally call "the judiciary system", has seen and sees a very large number of successful Italian Americans. This is very important, because it means that not only they were able to reach economic success and make money, as we've already seen; but that they also gained the trust of the American people, being lawyers or prosecutors or judges, from the local level up to the Supreme Court.

To address this topic we're meeting one of those successful Italian Americans: Francis Donnarumma is a lawyer, the Secretary of the National Italian American Bar Association and Past President of the Connecticut Italian American Bar Association

Fran, what's the story of your Italian family, and when did it become an Italian American story?

My family's story really began on one mountain top, in Italy, in the province of Avellino. It is a typical story. Francesco Donnarumma, my grandfather, was born in the town of Frigento and my other grandfather, Michele Giordano, was born on the very same mountain top, in the town called Sturno. The two young men – twelve and fourteen years old – left Italy and came to US around 1910. They had not known know each other in Italy. Each arrived in Waterbury, Connecticut. Serendipity: Francesco's son, my father, Carmine, met Michele's daughter, Louise, my mother, and they married.

All came to Waterbury because of the factories that were begging for workers at that time. Waterbury's population total was maybe 30,000 people. In the course of twenty to thirty years about 10,000 emigrants came from Italy, just to Waterbury. It was a phenomenal attraction here, perhaps, led by poverty in southern Italy and emerging industry here in the States. Francesco became a butcher, Michele became a school custodian, and they had their children, my mother and father.

My father, Carmine, was an academic natural. He studied in New York and was hired with the initial faculty at the Jesuit Fairfield University. He enjoyed his whole career there, until he retired. Upon retirement, the University memorialized him, naming "Donnarumma Hall", the faculty office building. Almost all the other buildings are named after saints, so it was really a wonderful honor.

The coincidence is, again, Giordano and Donnarumma were from the same little mountain top: in Italy, they did not know each other and, yet, their lives intersected, somehow.

At the beginning of the mass emigration, Americans had a very low consideration of the Italians immigrated to the US. Now we have two Italian Americans Judges in the Supreme Court, and other important Italian Americans all over the US are successful judges, prosecutors and lawyers. How did this 180-degree turn happen? How did those people realized and succeeded to become that important and recognized?

I was given a great book about the earliest Italians in Boston, "The Boston Italians". The author is Stephen Puleo. He tracks another Italian who arrived from Salerno before 1900, James Donnarumma, who founded a newspaper called "La Gazzetta" which is still published by his granddaughter, Pamela Donnarumma. The author chronicles the abusive rhetoric directed to our ancestors, upon arrival in the States. Newspapers described them as similar to monkeys and chimpanzees. Public officials of the time spoke about their propensity to violence. In response, I believe, the Italians who came in that generation were driven to work harder than anybody, to preserve cohesive families, and to be assimilated into the US. During World War II, Italian Americans proportionally served in the US armed forces in far greater numbers than any other immigrant group. After the war, the young men who survived spread out all over the US and became successful in every field of endeavor.

My grandfather, Michele Giordano, fought in the World War I in the US Army. He was driven by the will to become American. He did not lose his Italian identity, but was driven to serve his new land. Later he became a national leader among Italian American war veterans as the vice president of the National Association of Italian American War Veterans.

Is there an Italian American who - according to you - can perfectly represent the contribution of the Italian Americans to the American judiciary system?

There is a quality of humanness and openness which I think is really distinctive among Italian American judges. Here, in Connecticut, in our own CIABA organization, we have several judges; Richard Marano, Salvatore Agati and Alice Bruno. I think that their Italian heritage gives them a great opportunity to identify with the litigants who are before them. There is the willingness to see the reality beyond the facts represented, obviously applying the law to the facts before them, but, also, seeing into someone's soul a little bit.

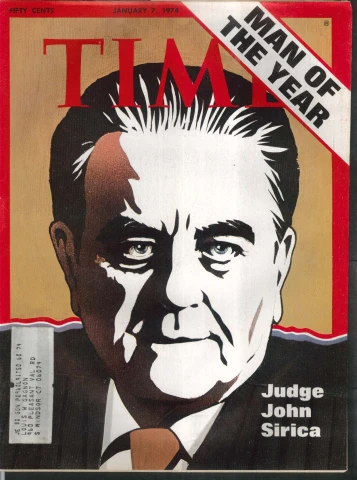

There is one historical figure, to answer your question: Honorable John Sirica. He was born in 1906, in my town, Waterbury, Connecticut. In those years, there were not many Italians able to study and, then, to become lawyers. He became an attorney and, later, was appointed as a United States District Court Judge in Washington, DC. He handled criminal matters. When President Richard M. Nixon engaged in what everyone ultimately recognized as grossly illegal conduct, some of the earliest associates of Nixon were presented before Judge Sirica. He was much criticized for his very aggressive questioning of the witnesses.

From my understanding, it was akin to the inquisitorial style of the Italian judiciary, where the judges were very active at examining witnesses. That was not the norm here, so Judge Sirica would often be criticized for stepping too far and being too involved. In the Watergate criminal trials he was very aggressive, as was his typical manner, because he knew the truth was not being revealed. Ultimately, he made the critical decision in the case known as United States v Nixon, wherein he ordered the White House, the Nixon White House, to turn over the secret tapes that ultimately broke open the case. His decision was immediately appealed to the United States Supreme Court, which upheld Judge Sirica's courageous decision. This is the beauty of the Italian history on the United States: the Sirica family from Italy arrives in Waterbury, Connecticut, their son goes to school, does good honest work, and finds himself in a political and legal storm that consumed our country. He acted boldly and successfully asserted the law against the most powerful man in the nation. He is really a heroic figure.

You are the Secretary of the National Italian American Bar Association. How many Italian American lawyers are members of this institution, and which are your main activities? Do you have local committees?

NIABA has existed for more than 30 years now. Our numbers are changing, what I can say is that the people with whom we are regularly communicating certainly are at least five thousand. We have wonderful constituencies all over the country. It was designed to be a freestanding association. We do not have branches throughout the country, but, we coordinate with other associations: the CIABA in Connecticut; the Italian Lawyers of Los Angeles in Southern California, and we are going to meet soon with an association in the San Francisco area, and another in Orange County, California.

Our directors come from the US - California, Florida, New England, Illinois, from many cities – but, also, Canada and Italy. What we do is promote Italian American lawyers: networking is our most direct benefit. We work with law schools, we publish a newsletter that gives information about Italian American lawyers and judges. We have a scholarly publication called "The Digest", published with the assistance of Professor Robin Malloy at the Syracuse Law School in New York.

We bring lawyers together. We move our board meetings around the country. We had our first seminar in Rome in October this year, and there were 25 American and 18 Italian lawyers present.

You also are Past President of the Connecticut Italian American Bar Association, CIABA. Are there many Italian judges, prosecutors and lawyers in the Constitution State?

I was president for three years recently. I am the first lawyer from Connecticut to become one of the four national officers, so I left being president in Connecticut. It is not only the law, not only the business networking opportunities: it is the kinship among the participants, what really is unique.

In Connecticut, among our directors is a lawyer, Louis Pepe, a very distinguished lawyer in our State, amongst our highest regarded lawyers. He is a past president of the Connecticut Bar Association and a member of 9 different lawyer associations. He always tells us: "No matter how many associations I am part of, the most fun is being part of CIABA." It is not just a professional association where you get seminars, knowledge, improve your particular skills, do what you have to do to move up the legal ladder of success: it is really more about coming together in a safe, relaxed environment, not competitive with the other members. During our meetings, there is something that has become a tradition. The first time it happened we did not know that it would become a tradition. One of our members, Mark Iannone, put a brown paper bag on the table and said "I'd like to discuss something with the board". I had no idea what he was getting at, and I said "Sure, Mark". He opened the bag and took out beautiful garlic, which he grows, a particular kind of garlic and he shared it, and somehow we look forward it year after year: "When is Mark bringing the garlic?"

And I am not saying it to play any stereotype, of course ... but we do not only talk about law, we talk about food, we have wonderful meetings all focused around food and wine, who is travelling to Italy, and we develop so many wonderful relations. In Italy, I visited the family of one of our members, Lorenzo Agnoloni, in Tuscany, and it was fantastic. I, also, went to Naples and met with the Neapolitan lawyer Giancarlo Pezzuti: he cleared his schedule and spent the whole day bringing us through Naples, and it was tremendous.

If you should mention one aspect of the American judiciary system that you'd like to bring into the Italian one, what would it be?

I confess I do not know so much about the Italian system. I do know that many Americans were perplexed about the Italian criminal system as we observed it through the eyes of American reporters in the Amanda Knox case. Then, I talked to Italian lawyers who spend work, as well, in the US, like Valerio Spinaci and Giancarlo Pezzuti. Both of them are sure we had a misimpression of the judicial system in Italy, because again, our knowledge comes through the glasses of American journalists reporting.

What I should emphasize is that in the American criminal justice system, the overarching goal is to protect the individual, at the expense of law enforcement, at the expense of the system. The protection of the individual rights is supreme, not to say that it is not in Italy. We have a much spoken explanation that "it is better that ten guilty persons go free than one innocent person being wrongly convicted". I think that is the trait of the American system. Certainly, in our system, we have many people who have been wrongly convicted; but the nature of the system is to focus on the individual and his rights. This emphasis sometimes causes public upset and, even, outrage; nonetheless, as lawyers, we must do as Judge Sirica did before us and follow the law as it leads us.

Uno dei campi più importanti e potenti della società americana, il sistema giudiziario, ha visto e vede un numero molto elevato di italoamericani di successo. Questo è molto importante, perché significa che non solo sono stati in grado di raggiungere il successo economico e fare molti soldi, come abbiamo già visto; ma che hanno anche guadagnato la fiducia del popolo americano, essendo avvocati o pubblici ministeri o giudici, dal livello locale fino alla Corte Suprema.

Per affrontare questo argomento incontriamo uno di questi italoamericani di successo: Francis Donnarumma è un avvocato, il Segretario Generale del National Italian American Bar Association e Past President del Connecticut Italian American Bar Association

Fran, qual è la storia della tua famiglia italiana, e quando diventa una storia italoamericana?

La storia della mia famiglia inizia sulla cima di una montagna, in Italia, in provincia di Avellino. Si tratta di una tipica storia. Francesco Donnarumma, mio nonno, nacque nella città di Frigento e l'altro mio nonno, Michele Giordano, nacque sulla cima della stessa montagna, nella città di Sturno. I due giovani – avevano dodici e quattordici anni - lasciarono l'Italia e vennero negli Stati Uniti intorno al 1910. Non si conoscevano, in Italia, e arrivarono entrambi a Waterbury, Connecticut. Il caso volle che il figlio di Francesco, mio padre Carmine, incontrò la figlia di Michele, mia madre Louise, e si sposarono.

Molti italiani arrivarono a Waterbury perché in quel momento le fabbriche cercavano disperatamente manodopera. La popolazione totale della città era di circa 30.000 persone, e nel corso di venti o trent'anni furono circa 10.000 gli emigrati provenienti dall'Italia che arrivarono a Waterbury, spinti dalla povertà nell'Italia meridionale e dall'economia che cresceva invece qui negli Stati Uniti. Mio nonno Francesco divenne un macellaio, mio nonno Michele divenne custode della scuola, e così nacquero i loro figli, mia madre e mio padre.

Mio padre, Carmine, studiò a New York e poi iniziò la carriera accademica alla Fairfield University, un'istituzione gesuita. Fece tutta la sua carriera lì, e al momento del suo pensionamento, l'Università ne riconobbe le doti nominando "Donnarumma Hall" il palazzo degli uffici della facoltà. Quasi tutti gli altri edifici hanno il nome di alcuni santi, quindi fu davvero un grande onore.

All'inizio dell'emigrazione di massa, gli americani avevano una bassissima considerazione degli italiani emigrati negli Stati Uniti. Ora abbiamo due italoamericani giudici della Corte Suprema, e altri importanti italoamericani in tutti gli Stati Uniti sono giudici di successo, pubblici ministeri e avvocati. Come hanno fatto queste persone a diventare così importanti e stimate?

Ho letto un gran bel libro sui primi italiani a Boston, "The Boston Italians". L'autore è Stephen Puleo. Tra gli altri, rintraccia un italiano che arrivò da Salerno prima del 1900, James Donnarumma, che poi fondò un giornale chiamato "La Gazzetta", ancora oggi pubblicato dalla nipote, Pamela Donnarumma. L'autore racconta degli abusi e degli stereotipi negativi diretti verso i nostri antenati, al momento dell'arrivo negli Stati Uniti. I giornali li descrivevano come simili a scimmie o scimpanzé. I funzionari pubblici dell'epoca davano per scontato che tutti loro avessero una naturale propensione alla violenza. In risposta, credo, gli italiani di quella generazione che arrivarono qui furono spinti a lavorare di più di chiunque altro, per preservare le famiglie coese, ed essere assimilati nella società americana. Durante la seconda guerra mondiale, gli italoamericani si arruolarono e combatterono nelle forze armate americane in numero proporzionalmente molto maggiore rispetto a qualsiasi altro gruppo di immigrati. Dopo la guerra, i giovani sopravvissuti, sparsi in tutti gli Stati Uniti, raggiunsero il successo in ogni campo di attività.

Mio nonno, Michele Giordano, combatté nella prima guerra mondiale nell'esercito degli Stati Uniti. Era guidato dalla volontà di diventare americano. Non aveva perso la sua identità italiana, ma voleva servire il suo nuovo Paese. Più tardi divenne un leader nazionale tra i veterani di guerra italoamericani, fino ad essere nominato Vice Presidente della loro Associazione Nazionale.

C'è un italoamericano che secondo te può rappresentare perfettamente il contributo degli italoamericani al sistema giudiziario americano?

C'è una qualità di umanità e di apertura che credo sia davvero distintiva tra i giudici italoamericani. Qui nel Connecticut, nella nostra organizzazione Connecticut Italian American Bar Association (CIABA), abbiamo diversi giudici: Richard Marano, Salvatore Agati e Alice Bruno. Credo che la loro origine italiana dia loro una grande capacità di identificarsi con le parti in causa nei confronti delle quali devono decidere. C'è la volontà di vedere la realtà al di là dei fatti rappresentati, ovviamente applicando la legge ai fatti, ma anche cercando di comprendere le persone per chi sono.

Effettivamente c'è una figura storica, per rispondere alla tua domanda: Sua Eccellenza John Sirica. Sirica nacque nel 1906 nella mia città, Waterbury, nel Connecticut. In quegli anni non molti italiani erano in grado di studiare e, quindi, in seguito diventare avvocati. Lui ci riuscì e, in seguito, fu nominato giudice della Corte Distrettuale di Washington, DC. Si occupava di giustizia penale. Quando il presidente Richard M. Nixon fu coinvolto in quello che ormai tutti riconoscono come un comportamento gravemente illegale, alcuni dei collaboratori del Presidente Nixon furono chiamati a deporre dal giudice Sirica. Egli fu molto criticato per l'aggressività dello stile che tenne nel suo interrogatorio. Per quanto io abbia compreso, era uno stile simile a quello inquisitorio della magistratura italiana, dove i giudici sono molto attivi nell'esaminare i testimoni. Qui la consuetudine era un po' diversa, così il giudice Sirica fu spesso criticato e incolpato di aver esagerato e di essere troppo coinvolto. In realtà, nel corso del Watergate Sirica fu molto aggressivo, seguendo quello che era sempre stato il suo stile, perché sapeva che la verità non era ancora stata rivelato. Alla fine, prese la decisione critica - nel caso noto come Stati Uniti contro Nixon – di ordinare all'Amministrazione Nixon di consegnare i nastri segreti, che alla fine risolsero il caso. La sua decisione fu immediatamente oggetto di appello alla Corte Suprema degli Stati Uniti, che però confermò la giustezza della coraggiosa decisione del giudice Sirica. Questa è la bellezza della storia degli italiani negli Stati Uniti: la famiglia Sirica arriva dall'Italia a Waterbury, Connecticut; il loro figlio va a scuola, fa un buon lavoro bene e onestamente, e si ritrova in una tempesta politica e giuridica che ha consumato il nostro Paese; e lui agisce con coraggio e afferma con successo il primato della legge sull'uomo più potente della nazione. Sirica è davvero una figura eroica.

Tu sei il Segretario Generale del National Italian American Bar Association, NIABA. Quanti sono gli avvocati italoamericani membri di questa istituzione, e quali sono le vostre principali attività? Esistono comitati locali?

NIABA esiste da più di 30 anni ormai. I nostri numeri stanno cambiando, quello che posso dire è che le persone con cui stiamo comunicando regolarmente certamente sono almeno cinquemila, e sono distribuiti in tutto il paese. NIABA è stata progettata per essere una associazione indipendente, non abbiamo filiali in tutto il paese ma ci coordiniamo con le altre associazioni: il CIABA nel Connecticut; gli Italian Lawyers of Los Angeles nella California del Sud; e presto incontreremo un'associazione simile nella zona di San Francisco, e un'altra a Orange County, in California.

I nostri vertici provengono dagli Stati Uniti - California, Florida, New England, Illinois e molte altre città - ma anche dal Canada e dall'Italia. Quello che facciamo è promuovere gli avvocati italoamericani: fare networking è il nostro più diretto beneficio. Lavoriamo con le facoltà di legge, pubblichiamo un bollettino che fornisce informazioni su avvocati e giudici italoamericani. Abbiamo una pubblicazione accademica chiamato "The Digest", pubblicata con l'aiuto del professor Robin Malloy della Syracuse Law School di New York.

Ci muoviamo: riuniamo i nostri consigli di amministrazione in varie parti del paese. Abbiamo avuto il nostro primo seminario a Roma nel mese di ottobre di quest'anno, e c'erano 25 americani e 18 avvocati italiani presenti.

Tu sei anche Past President del Connecticut Italian American Bar Association, CIABA. Ci sono molti giudici, pubblici ministeri e avvocati italoamericani nel Constitution State?

Sono stato presidente di recente, per tre anni. Sono il primo avvocato del Connecticut eletto ad una delle quattro cariche nazionali, così ho lasciato la presidenza della CIABA. L'importanza delle nostre riunioni non sta solo nel fatto che siamo tutti uomini di legge, e nemmeno se ci aggiungiamo le opportunità di networking abbiamo spiegato tutto: è il sentimento di fraternità tra i partecipanti, quello che è davvero unico.

Tra i nostri direttori nel Connecticut c'è un avvocato, Louis Pepe, molto apprezzato nel nostro Stato, tra i nostri membri più riconosciuti. Lui è un ex presidente del Connecticut Bar Association ed è membro di 9 diverse associazioni di avvocati. E ci dice sempre: "Non importa di quante associazioni io faccia parte, la cosa più divertente per me è essere parte della CIABA". Non è solo un'associazione professionale in cui si organizzano seminari, si fanno nuovi incontri, si migliorano le proprie abilità e conoscenze, si conduce l'attività che ci permette di crescere e avere sempre più successo nel mondo legale: la realtà è che altrettanto importante e forse anche di più è il fatto di riunirci in un ambiente rilassato e sicuro, non competitivo con gli altri membri. Durante i nostri incontri, c'è una cosa che è diventata una tradizione. Naturalmente, la prima volta che accadde non sapevamo che sarebbe diventata una tradizione: uno dei nostri membri, Mark Iannone, mise un sacchetto di carta marrone sul tavolo e disse "mi piacerebbe discutere di una cosa con il consiglio". Io non avevo idea di dove volesse arrivare, così gli dissi "Certo, Mark". Aprì la borsa e tirò fuori un bellissimo spicchio d'aglio, un particolare tipo di aglio che coltiva lui stesso, e lo distribuì a tutti noi ... e adesso ogni volta non vediamo l'ora che lo faccia di nuovo, anno dopo anno: "Quand'è che Mark porta l'aglio?".

E non voglio cadere in alcuno stereotipo, certo ... ma nelle nostre riunioni non si parla solo di legge, ma anche di cibo e di vino, di chi ha recentemente viaggiato in Italia, e sviluppiamo tante relazioni meravigliose. Ad esempio, io in Italia ho visitato la famiglia di uno dei nostri membri, Lorenzo Agnoloni, in Toscana, ed è stato fantastico. Inoltre sono andato a Napoli a trovare il mio amico Giancarlo Pezzuti, avvocato napoletano: ha cancellato tutti i sui impegni e ha passato tutto il giorno facendomi visitare Napoli, ed è stato meraviglioso.

C'è un aspetto del sistema giudiziario americano che consiglieresti di inserire anche in nel sistema giudiziario italiano?

Confesso che non conosco benissimo il sistema italiano. So che molti americani sono rimasti perplessi sul sistema penale italiano, conoscendolo attraverso gli occhi dei giornalisti americani, in occasione del caso di Amanda Knox. Poi, ho parlato con avvocati italiani che sono spesso in America, come Valerio Spinaci e Giancarlo Pezzuti. Entrambi mi hanno assicurato che è stata data un'impressione sbagliata del sistema giudiziario in Italia, perché la nostra conoscenza passa attraverso i racconti e i servizi dei giornalisti americani.

Quello che tengo a sottolineare è che nel sistema di giustizia penale americano l'obiettivo generale è quello di proteggere l'individuo, a scapito delle forze dell'ordine e del sistema. La protezione dei diritti individuali è suprema, ma non sto dicendo che non sia così anche in Italia. Qui in America abbiamo un detto: "è meglio che dieci colpevoli siano in libertà piuttosto che un'innocente in carcere ingiustamente condannato". Credo che questo sia la sintesi del sistema americano. Certo, nel nostro sistema, abbiamo molte persone che sono state condannate ingiustamente; ma la natura del sistema è quella di concentrarsi sulla persona e i suoi diritti. Questa enfasi a volte sconvolge e fa arrabbiare molti; tuttavia, come avvocati, dobbiamo comportarci come si comportò il giudice John Sirica e seguire sempre la legge.