I have always thought, perhaps driven by my love for the Italian American community and the history of its achievements, that the greatest American athlete of all time is Joe DiMaggio, who belonged to that community. There is obviously no official ranking, everybody has their own, mine sees there at the top a very great Italian American.

Someone who knows much, but much more about it than I do is Prof. Lawrence Baldassaro, who on baseball and Italian Americans has written volumes unbeatable in style, detail and content. It is a privilege and honor for me to be able to interview him.

Prof. Baldassaro, welcome to We the Italians. Please tell us something about your Italian heritage and your passion for baseball

I’ve been passionate about baseball for as long as I can remember, but there was a time when I couldn’t have imagined writing a book about Italian American ballplayers, or even about anything Italian.

I had the good fortune to grow up in a home with a second- generation Italian American father and an Italian-born mother and grandmother. But as a child I didn’t fully appreciate my Italian heritage. For those of us growing up in the 1950s, there was little incentive to be ethnic. We all wanted to assimilate, even if we didn’t know what that meant. That’s why when my grandmother spoke to me in her Abruzzese dialect, which I understood, I would answer in English.

But then I went to Italy in the summer between my junior and senior years in college, and that changed everything. First, I discovered my cultural roots when I saw the magnificent art and architecture in Florence and Rome. Then I discovered my personal roots when I visited my mother’s family in Abruzzo, most of whom still lived in the farm compound where my mother was born 55 years earlier. All they knew about me was that I was my mother’s son, but they welcomed me not as a stranger, but as a long-lost son returning home.

That’s when I finally understood and embraced my ethnic heritage. And that’s when I decided to dedicate my professional life to studying and teaching Italian language and literature.

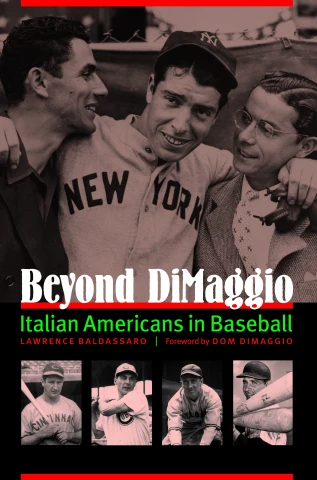

Your first book I would like to ask you about is from 2011: “Beyond DiMaggio: Italian Americans in Baseball”. Leaving aside for a moment the protagonist of your latest book and of a subsequent question in this interview, what are the most important Italian American names that represent this legacy?

Beyond DiMaggio is the first extensive history of Italian Americans in baseball. I wrote the book to preserve the legacy of those who not only made great contributions to baseball, but whose success and dignity countered negative stereotypes and enhanced the public perception of Italian Americans.

Athletes of Italian descent have achieved distinction in virtually every American sport. But in no sport has their success been more enduring or more socially significant than it has in baseball. While doing the research for Beyond DiMaggio I discovered that, in many ways, the history of Italian American involvement in baseball mirrors the experience of Americans of Italian descent. The early players encountered prejudice, expressed primarily through ethnic slurs and stereotypical portrayal by the media. Later came greater acceptance, especially in the years following World War II. In the following decades there were fewer players of Italian descent, but there was upward mobility from labor to management.

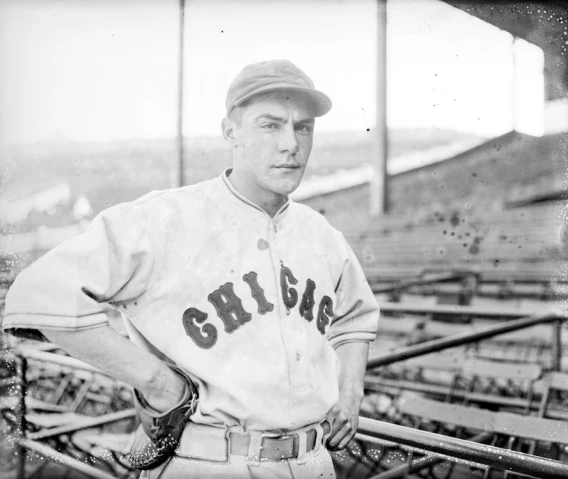

At the end of the 19th century, when baseball was dominated by Anglo, German and Irish Americans, Italian American ballplayers were not welcome. The first major league player clearly identifiable as Italian American was Ed Abbaticchio, who enjoyed a successful nine-year career between 1897 and 1910. But he would prove to be an anomaly. By the mid-1920s only 15 players of Italian descent had played in the major leagues, most of those for brief periods, and some had changed their names to hide their ethnic identity.

Ethnic bias was not the only impediment faced by ballplayers hoping to play professionally. Most immigrant parents considered baseball to be a waste of time. Dario Lodigiani, a San Francisco native who would spend six years in the major leagues between 1938 and 1946, told me that his father was initially opposed to his son’s wishes. “You want to become a ballplayer? You’ll become a bum,” he said. But when Dario was playing for the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League in his first year out of high school and was making more than his dad at $150 a month, his father said: “Boy, you’ve got a good job.”

At one point his father, who knew almost nothing about baseball, even gave him a batting tip. Having heard a radio announcer say during a game that Dario had hit a popup, he asked his son what that meant. “That’s when I hit the ball under the center and it goes straight up into the air,” Dario explained. “I know what you do,” his father replied. “Put one of those inner soles in your shoe, then you’ll be taller and you’ll hit the ball in the middle.”

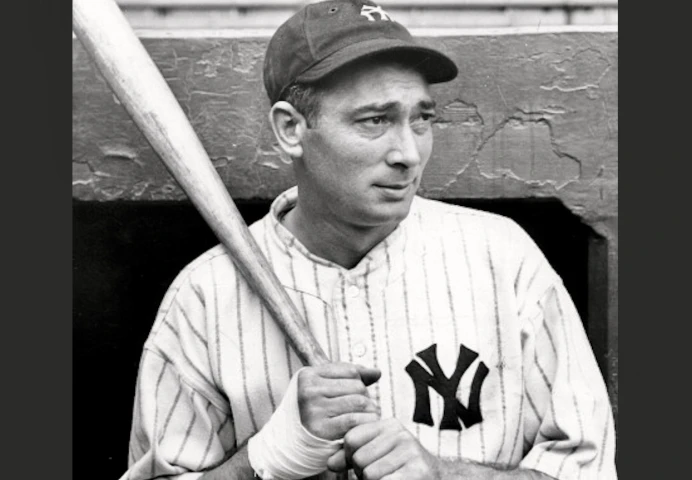

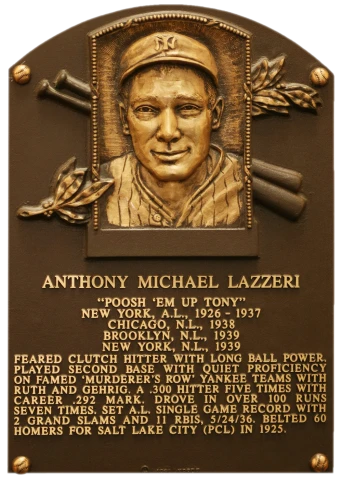

The first major star of Italian descent was Tony Lazzeri, another native of San Francisco and the son of immigrants. From 1926-37, he was the starting second baseman for the great New York Yankees teams that won five World Series, and one of the most popular players in baseball. More will be said about Lazzeri later.

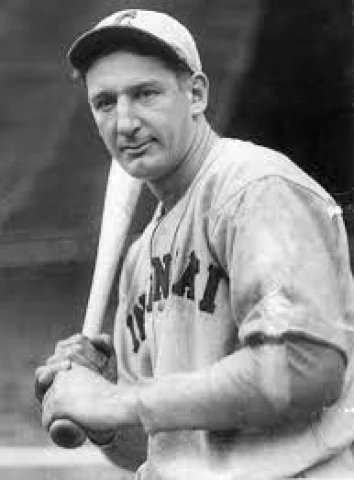

In the 1930s Italian American participation in the major leagues increased dramatically with at least 54 making their debut. Some made brief appearances, but many enjoyed lengthy careers and two - Joe DiMaggio and Ernie Lombardi - would be enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

This unprecedented influx triggered an equally unprecedented response from the media, which treated their arrival with an ambiguous attitude not unlike that which had greeted Italian immigrants since the late nineteenth century. Some saw the growing number of Italian players as a threat to the traditional domination of Irish players, thus invoking the ethnic tensions that had existed for so long between these two groups.

In 1934 Boston Globe sports columnist Gene Mack wrote that “spaghetti may soon become the national dish of the national game. Cuccinello, Puccinelli, Crosetti, Lazzeri, Bonura, Orsatti, DiMaggio and a host of other ‘walloping Wops’ can’t be wrong. The Italians are in this business to stay.” His accompanying illustration depicted 13 ballplayers seated around a table featuring a large bowl labeled “spaghetti.”

Of the players who made their debut in the 1930s, Lombardi, DiMaggio, Dolph Camilli and Phil Cavarretta became the first Italian Americans to win a Most Valuable Player Award.

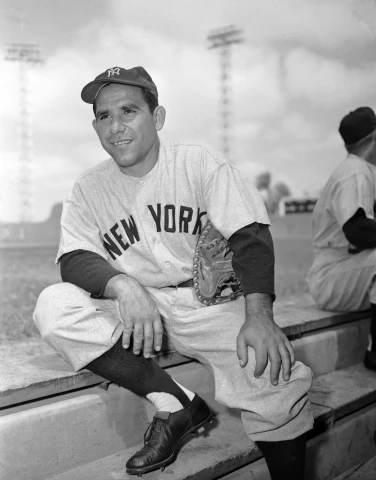

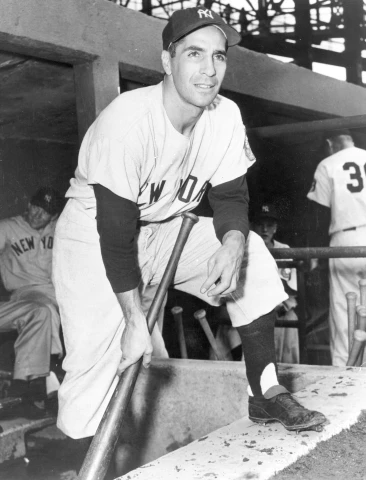

It was during the years following World War II that Italian Americans reached the pinnacle of their success in baseball. At that time New York City was the center of the baseball universe. Between 1947 and 1958, the Yankees won ten pennants and eight World Series, the Dodgers six pennants and one Series, while the Giants won two pennants and one Series.

Players of Italian descent played key roles on all three New York teams, achieving unprecedented visibility and prominence. They included: Joe DiMaggio, Yogi Berra, Phil Rizzuto, Vic Raschi and Billy Martin (Yankees); Roy Campanella, Carl Furillo and Ralph Branca (Dodgers); Sal Maglie and Johnny Antonelli (Giants). DiMaggio, Rizzuto, Berra and Campanella won MVP awards and ended up in the Hall of Fame.

In the years following World War II, the open use of ethnic epithets gradually decreased. But that didn’t mean there was no more prejudice. Hall of Famer Joe Torre, born in 1940, told me: “When I was growing up I asked my mom, ‘What nationality are we?’ She’d say, ‘You’re American.’ I sensed that unless you were an American, you had something to be ashamed of in those days.

As the years passed, second- and third-generation players of Italian descent were increasingly likely to be the offspring of mixed marriages, to have little or no familiarity with the Italian language, and to consider themselves, first and foremost, “American.”

This is not to say that Italian American fans did not recognize and celebrate stars such as Rocky Colavito, Tony Conigliaro, Rico Petrocelli, Joe Torre and Ron Santo. However, the media were much less likely to take note of a player’s ethnic background and, as time went on, the players were less likely to identify themselves as Italian Americans.

In addition to the ten individuals identified above as members of the Baseball Hall of Fame, there are three other more recent inductees.

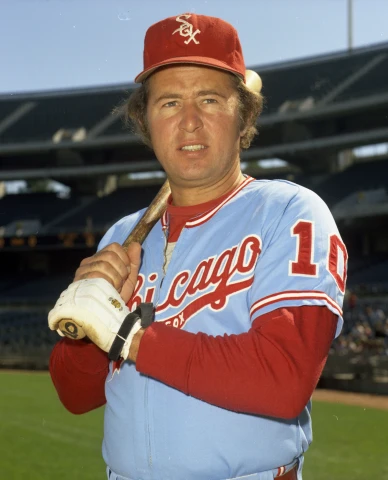

A native of Seattle, Ron Santo overcame numerous challenges, including being diagnosed with diabetes at the age of 18, to forge a Hall of Fame career. In his 14 years (1960-73) as the slugging third baseman for the Chicago Cubs, he was a nine-time All-Star. Following his retirement, in 1990 he became the color analyst for the Cubs radio broadcasts, a position he held until his death in 2010 at the age of 70. In 2003 the Cubs retired his uniform number 10, and in 2011 they erected a statue of him outside Wrigley Field.

Complications from diabetes led to several medical procedures over the last decade of his life, including amputation of both legs below the knees. During those years we would often meet when the Cubs came to Milwaukee and, despite his many afflictions, he never lost his positive attitude and his self-deprecating sense of humor. In 2012 he was posthumously elected to the Hall of Fame.

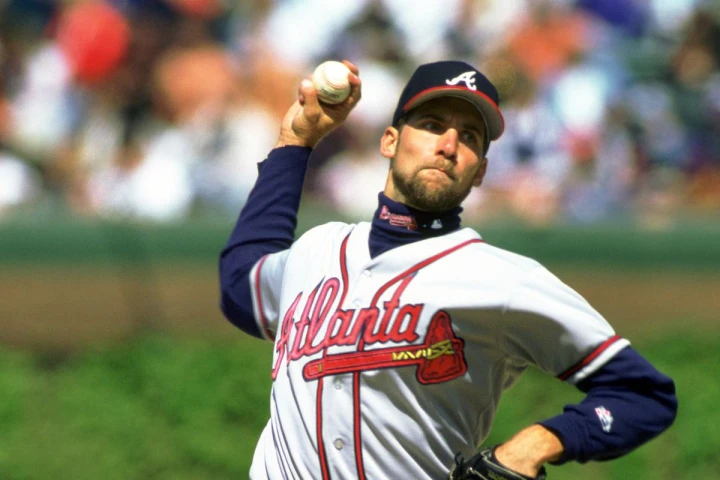

The other two Hall of Famers of Italian descent (John Smoltz and Craig Biggio) were both inducted in 2015.

John Smoltz was one of those rare pitchers who excelled both as a starter and as a reliever. He was with the Atlanta Braves for the first 20 years of his 21-year career (1988-2008). In his first 12 years he was a starter, winning the Cy Young Award as best pitcher in the National League in 1996. In 2002 he became the Braves “closer,” leading the league with 55 “saves.” He returned to the starting rotation in 2005, compiling a record of 44-24 over the next three seasons. An eight-time All-Star, he twice led the league in wins.

Of Italian heritage on his mother’s side, he said of his maternal grandmother, who lit candles and prayed every time he pitched: “She was a full-blooded Italian, the greatest cook in the world, and I loved her to death.”

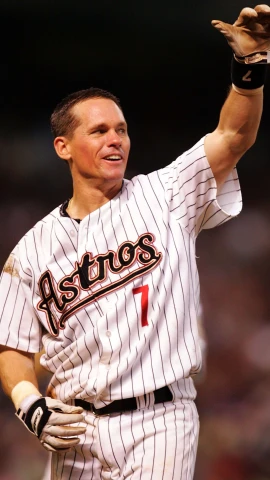

Craig Biggio was an anomaly in the free-agent era of baseball, spending his entire 20-year career (1988-2007) with one team, the Houston Astros. But within that one team he was an extraordinarily multi-talented player. In his first four seasons, he was a two-time All-Star as a catcher. He then moved to second base, where he was an All-Star in five of his first six seasons and won four Gold Glove Awards. Then, after 11 years at second, he made yet another smooth transition by playing center field.

His hitting was no less impressive than his fielding. In 2007 he became the 27th player in major league history to record 3,000 hits, and he is the only player to reach all these milestones: 600 doubles, 250 home runs, and 400 stolen bases. The Astros erected a statue of him outside Minute Maid Park in 2003 and retired his uniform number 7 in 2008.

When I spoke with Biggio in 2005, I asked what motivated him to continue playing after 18 seasons. “Just the game itself,” he said. “You get to compete against the best players in the world, and I cherish that.”

Italian Americans have gained prominence off the field as well…

Yes. While it is true that in the latter decades of the 20th century fewer players of Italian descent were entering the big leagues, at the same time they were experiencing upward mobility in baseball, moving into management positions, as on-field managers, front office executives, and owners. Since 1981, for example, ten managers, three of whom (Tommy Lasorda, Tony La Russa and Joe Torre) are in the Hall of Fame, have taken their teams to a total of 24 World Series, winning 15 of them. Torre was also a nine-time All-Star as a player and served as Major League Baseball’s chief operating officer from 2011 to 2020. And, in 1989, an Italian American was named to the game’s highest post, Commissioner of Baseball.

No one, I think, better epitomizes the evolution, and social significance, of Italian Americans in baseball, or in American society, for that matter, than A. Bartlett (“Bart”) Giamatti. His father, the son of immigrants, earned a PhD at Harvard and was a professor of Italian at Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, Massachusetts. Born in 1938, Bart was passionate about baseball and was a lifelong Boston Red Sox fan.

After attaining a PhD, he taught comparative literature at Yale, where he established a solid reputation both as a teacher and a scholar of Renaissance literature, focusing on the influence of Italian Renaissance writers on English literature. Then, in 1978, in the same city where his immigrant grandfather had worked in a factory, he was named president of Yale at the age of 39, the youngest ever to hold that post.

In 1986 he gave up that position at one of America’s most prestigious universities to become president of Major League Baseball’s National League. He had captured the attention major league officials by writing eloquently about baseball’s role as the quintessential American game.

Then, on April 1, 1989, he was named seventh Commissioner of Major League Baseball. Within two generations, the grandson of an Italian immigrant had risen to the pinnacle of America’s national game. Not gifted with the talent to play the game, Giamatti found another way to realize the dream of becoming a major leaguer that he shared with so many of his generation.

Sadly, he died six months later, victim of a heart attack at the age of 51. But even though he had little chance to prove what he might have accomplished, his love of the game, demonstrated both in his defense of its traditions and his eloquent celebrations of its meaning, were enough to convince many of his unique status in the game. New York Times columnist Ira Berkow speculated that Giamatti, “this most cultured and civilized and warm and generous and witty man... might have become the best baseball commissioner we’ve ever had. He had brains, sinew, and the best wishes of the game.”

For Giamatti, the ultimate fan who saw in the game he loved a clear expression of the national psyche, baseball became a metaphorical expression of the American Dream, not as material fulfillment but as a spiritual quest for home. In fact, the significance of his impact on baseball is not just that he rose to its highest office, but that he was also one of its most passionate and articulate exponents. He understood better than most the nature and significance of the immigrant experience, and he wrote about it eloquently. “The basic rhythm of baseball,” he wrote, “the going out and the subsequent quest to return home, is part of the plot of the story of our national life, the story of how difficult it is to find the origins one so deeply needs to find. The concept of home has a particular resonance for a nation of immigrants, all of whom left one home to seek another.”

A few of the individuals portrayed in Beyond DiMaggio found unimaginable fame and fortune by playing baseball. Most found more modest success. But they all had one thing in common, in addition to their ethnic heritage; they all made a living playing the quintessential American game, a game that for many was the very symbol of the values and promises of the country to which their forebears had immigrated.

Why Joe DiMaggio, more than any other, has become the symbol of these talented Italian American baseball players?

One of the most recognizable and popular men in mid-20th century America, Joe DiMaggio was celebrated in song and literature as an iconic hero. Following his death in 1999, the US House of Representatives passed a resolution honoring him “for his storied baseball career; for his many contributions to the nation throughout his lifetime; and for transcending baseball and becoming a symbol for the ages of talent, commitment and achievement.”

But first and foremost, Joe DiMaggio was a ballplayer. He was the undisputed leader of New York Yankees teams that won nine World Series titles in his 13-year career that ran from 1936 to 1951, with three years lost to military duty in World War II. He was three times the American League’s Most Valuable Player, and he holds what many consider to be the most remarkable baseball record of all, a 56-game hitting streak in 1941. As the son of immigrants, he was the embodiment of the American Dream.

In the eyes of his contemporaries, Joe DiMaggio was universally considered the best player they had ever seen. Even his arch-rival, Ted Williams, said “he was the greatest baseball player of our time. He could do it all.” For former New York Governor Mario Cuomo, DiMaggio’s life “demonstrated to all the strivers and seekers - like me - that America would make a place for true excellence whatever its color or accent or origin.”

One of those rare athletes who transcended the world of sport, DiMaggio has been called by more than one writer the last American hero. When he died, his enduring status as a cultural icon was confirmed by an outpouring of adulation which few public figures, in any walk of life, could evoke. His death was front-page news in every major newspaper and was covered extensively on television newscasts and specials. As one Brooklyn native put it, DiMaggio “epitomized an era when, for a lot of us, baseball was the most important thing in life.”

Two of Joe’s brothers also had impressive major-league records. Vince, the oldest of the three and, like Joe, a center fielder, was a two-time All-Star in a ten-year career. Dom, the youngest, was a seven-time All-Star center fielder for the Boston Red Sox. I had the opportunity to meet Dom in 2002 when he was an invited guest at the All-Star Game in Milwaukee. Not only did he accept my request to interview him, he even invited me to sit with him in the VIP section at the All-Star Game. Of all the major leaguers I have met over the years, none was more engaging, intelligent, or eloquent than Dom. I will forever be grateful that he agreed to write the Foreword to Beyond DiMaggio.

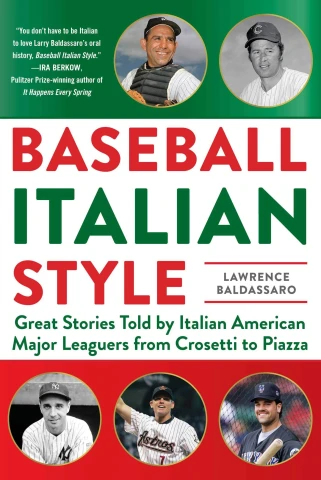

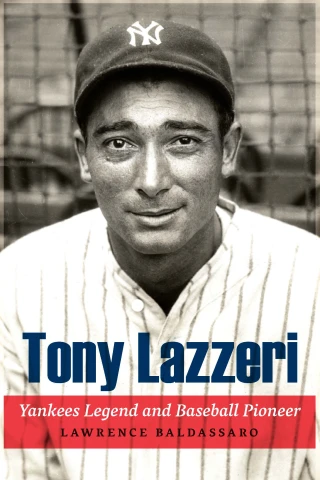

Before there was Joe DiMaggio, there was Tony Lazzeri, as your latest book says: “Tony Lazzeri: Yankees Legend and Baseball Pioneer”. Please tell us about him

I admit that until I was working on Beyond DiMaggio I knew very little about Tony Lazzeri other than that he was a Hall of Fame second baseman for the great Yankees teams of the 1920s and 30s. When I learned that he was one of the most celebrated ballplayers of his era, I felt like I had discovered a buried treasure and decided to make an effort to restore him to his rightful place in baseball history.

In the 12 years that he played for the New York Yankees (1926-37), at a time when baseball ruled the world of sports and was a major social institution, Tony Lazzeri was one of the game’s biggest stars. A key member of the Yankee dynasty that won six pennants and five World Series over that span, he was lauded by his peers and the press as one of the best and smartest players of his era. Legendary sports columnist Red Smith called him “as great a player as ever lived. In all his time with the Yankees there was no one whose hitting and fielding and hustle and fire and brilliantly swift thinking meant more to any team.”

A San Francisco native born to Italian immigrants, Lazzeri was signed by the Yankees after he hit 60 home runs in 1925 for the Salt Lake City Bees of the Pacific Coast League, the first time that number had been reached in the history of organized baseball. The next season the 22-year-old rookie second baseman was in the Yankees starting lineup alongside Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. He immediately emerged as a star, finishing second to Ruth in RBIs and third in home runs in the American League.

One of the first middle infielders to hit with power, during his time with the Yankees he was the third most productive hitter (after Ruth and Gehrig) in their legendary lineup, driving in more runs than all but five American League players and hitting more home runs than all but six. He also set marks that neither Ruth nor Gehrig reached; he still holds the American League record for RBIs in a single game (11) and was the first player (and one of only 13) to hit two grand slams in one game.

In addition, Lazzeri was recognized by his peers and the press as a natural leader who possessed one of the keenest baseball minds of his era. Even as a rookie, he was acknowledged as the de facto captain of the team. Frank Crosetti, his teammate from 1932 to 1937, said: “He not only was a great ballplayer, he was a great man. He was a leader. He was like a manager on the field.” And while Lazzeri was notoriously quiet, he had a keen sense of humor; his locker-room pranks endeared him to his teammates. His hitting, leadership ability and modest demeanor also made him a favorite of Yankee fans, second in popularity only to Babe Ruth.

What makes his accomplishments even more remarkable is that he played his entire career while afflicted with epilepsy, a condition so stigmatized at the time that it was kept a secret from fans. But over time his achievements would be overshadowed by those of his iconic teammates Ruth and Gehrig and he became an overlooked figure.

But to my mind, even more than for his baseball heroics, Lazzeri deserves to be remembered for his social impact as the first major star of Italian descent in Major League Baseball. His fame and popularity in the national pastime instilled in his fellow Italian Americans a newfound sense of pride. A symbol of their own hopes of finding a home in a new land that was not always welcoming, he quickly became a hero who was honored at banquets in several cities. Following a 1927 banquet in New York City attended by more than 1,000 people, the New York Times reported that “speeches lauding the brilliant work of the popular infielder and his exemplary conduct off and on the field rang through the grand ballroom.”

Such was his appeal that he inspired a generation of previously skeptical and uninterested immigrants to connect with baseball. For the first time Italian Americans flocked to ballparks, some waving Italian flags, to cheer for the young star.

It is difficult, I believe, to overestimate Lazzeri’s impact in countering negative images of Italians. With his modest demeanor, strong work ethic and quiet leadership, he was the antithesis of all the stereotypes that had been lodged in the public consciousness for decades. It may well be that at a time of unprecedented nationwide media coverage of baseball, he did more than anyone before him to enhance the public perception of Italian Americans. Given his modest, unassuming nature, that was clearly not a role he sought, but he proved to be the right person at the right time to fill it.

Italian baseball has been back in the spotlight lately, thanks to Mike Piazza, one of the greatest champions in recent baseball history, who now coaches the Italian national team and has brought several Italian American players and prospects with the Italian national team's blue jersey. We the Italians is a media partner of the Federazione Italiana Baseball e Softball and we also had the honor of awarding Mike with our "Two Flags One Heart award" at our 2022 gala...

Not surprisingly, the further removed they are from the immigrant generation, the less likely individuals are to have a strong sense of ethnic identity. Players whose careers began in the 1970s and later still expressed pride in their Italian heritage, and some expressed regret that they had not learned to speak Italian, but they were more likely to think of themselves as “American.” But there are those who do maintain a strong sense of ethnic identity.

None of the younger players I have met impressed me more than Mike Piazza. A 12-time All-Star in his 16-year career, he holds the record for most home runs by a catcher (396) and hit over .300 ten times. Widely considered to be the best offensive catcher ever, he was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2016. Yet for all he has achieved, I found him to be remarkably humble. I was also impressed by his awareness of, and genuine commitment to, his Italian heritage.

Piazza has long been involved with efforts to promote the development of baseball in Italy. He was part of Team Italy in the first three World Baseball Classics, as a player and coach, and he is now the manager of the Italian national team. I first met him in 2006 when he was the star of Team Italy in the inaugural World Baseball Classic. Seeing him play with such enthusiasm and joy, it was obvious he was not there for personal glory, but for the pride of representing the country where his grandparents were born. “I wouldn’t have missed this for the world,” he told me at the time. “It’s important to reconnect with your roots.”

I had the chance to talk with him several more times when his team would come to Milwaukee to play the Brewers. Each time he impressed me with his knowledge of the history of Italian Americans in baseball. In 1997 he had a career-high average of .362. Amazingly, that was only good enough for third place in the league. “I really wanted to be the first catcher since Ernie Lombardi to win the batting title [in 1938 and 1942],” he told me.

In 2002 he made his first trip to Italy, where, as part of Major League Baseball’s effort to internationalize the game, he conducted clinics for young Italian players. “I’ve been back several times since,” he told me. “I’ve always looked for a bridge between the Italians who stayed and the people who migrated here. We grew up in the United States and we love this country, but we’re very proud of our ancestry, the fact that Italy is a country of historical tradition. That’s what I find fascinating.”

Ho sempre pensato, forse spinto dal mio amore per la comunità italoamericana e la storia dei suoi successi, che il più grande atleta americano di tutti i tempi sia stato Joe DiMaggio, che a quella comunità apparteneva. Non c’è ovviamente una classifica ufficiale, ognuno ne ha una tutta sua, la mia vede lì in cima un grandissimo italoamericano.

Qualcuno che ne sa molto, ma molto più di me è il Prof. Lawrence Baldassaro, che sul baseball e gli italoamericani ha scritto volumi imbattibili per stile, dettagli e contenuti. E’ un privilegio e un onore per me poterlo intervistare.

Prof. Baldassaro, benvenuto su We the Italians. Ci parla delle sue origini italiane e della sua passione per il baseball?

Sono appassionato di baseball da sempre, ma un tempo non avrei mai immaginato di scrivere un libro sui giocatori di baseball italoamericani, o addirittura su qualcosa di italiano.

Ho avuto la fortuna di crescere in una casa con un padre italoamericano di seconda generazione e una madre e una nonna di origine italiana. Ma da bambino non apprezzavo appieno la mie origini italiane. Per quelli di noi che sono cresciuti negli anni Cinquanta, c'erano pochi incentivi a essere etnici. Volevamo tutti assimilarci, anche se non sapevamo cosa significasse. Ecco perché quando mia nonna mi parlava nel suo dialetto abruzzese, che io capivo, rispondevo in inglese.

Ma poi sono andato in Italia nell'estate tra il terzo e l'ultimo anno di università e questo ha cambiato tutto. Innanzitutto, ho scoperto le mie radici culturali quando ho visto la magnifica arte e architettura di Firenze e Roma. Poi ho scoperto le mie radici personali quando ho visitato la famiglia di mia madre in Abruzzo, la maggior parte della quale viveva ancora nella fattoria dove mia madre era nata 55 anni prima. Tutto ciò che sapevano di me era che ero il figlio di mia madre, ma mi hanno accolto non come un estraneo, ma come un figlio perduto da tempo che tornava a casa.

È stato allora che ho finalmente capito e abbracciato le mie radici. Ed è stato allora che ho deciso di dedicare la mia vita professionale allo studio e all'insegnamento della lingua e della letteratura italiana.

Il primo libro di cui vorrei chiederle è del 2011: "Beyond DiMaggio: Italian Americans in Baseball". Tralasciando per un momento il protagonista del suo ultimo libro e di una domanda successiva, quali sono i nomi italoamericani più importanti che rappresentano questa eredità?

Beyond DiMaggio è la prima storia approfondita degli italoamericani nel baseball. Ho scritto questo libro per preservare l'eredità di coloro che non solo hanno dato un grande contributo al baseball, ma il cui successo e la cui dignità hanno contrastato gli stereotipi negativi e migliorato la percezione pubblica degli italoamericani.

Gli atleti di origine italiana si sono distinti in quasi tutti gli sport americani. Ma in nessuno sport il loro successo è stato più duraturo e socialmente più significativo come nel baseball. Durante le ricerche per Beyond DiMaggio ho scoperto che, per molti versi, la storia del coinvolgimento degli italoamericani nel baseball rispecchia l'esperienza degli americani di origine italiana. I primi giocatori hanno incontrato pregiudizi, espressi principalmente attraverso insulti etnici e ritratti stereotipati da parte dei media. In seguito è arrivata una maggiore accettazione, soprattutto negli anni successivi alla Seconda guerra mondiale. Nei decenni successivi i giocatori di origine italiana sono diminuiti, ma c'è stata una mobilità verso l'alto dal lavoro ai dirigenti.

Alla fine del XIX secolo, quando il baseball era dominato da angloamericani, tedeschi e irlandesi, i giocatori italoamericani non erano ben accetti. Il primo giocatore della Major League chiaramente identificabile come italoamericano fu Ed Abbaticchio, che ebbe una carriera di successo di nove anni tra il 1897 e il 1910. Ma si sarebbe rivelato un'eccezione. A metà degli anni Venti solo 15 giocatori di origine italiana avevano giocato nelle Major League, la maggior parte per brevi periodi, e alcuni avevano cambiato nome per nascondere la propria identità etnica.

I pregiudizi etnici non erano l'unico ostacolo affrontato dai giocatori di baseball che speravano di giocare a livello professionale. La maggior parte dei genitori immigrati considerava il baseball una perdita di tempo. Dario Lodigiani, un nativo di San Francisco che avrebbe trascorso sei anni nelle Major League tra il 1938 e il 1946, mi ha raccontato che suo padre inizialmente era contrario ai desideri del figlio. "Vuoi diventare un giocatore di baseball? Diventerai un barbone", mi disse. Ma quando Dario giocava per gli Oakland Oaks della Pacific Coast League nel suo primo anno di scuola superiore e guadagnava più di suo padre con 150 dollari al mese, suo padre disse: "Ragazzo, hai un buon lavoro".

A un certo punto il padre, che non sapeva quasi nulla di baseball, gli diede persino un consiglio di battuta. Avendo sentito uno speaker radiofonico dire durante una partita che Dario aveva colpito un popup, chiese al figlio cosa significasse. "È quando colpisco la palla sotto il centro e questa va dritta in aria", spiegò Dario. "So cosa devi fare", rispose il padre. "Metti una di quelle suole interne nelle scarpe, così sarai più alto e colpirai la palla al centro".

La prima grande star di origine italiana fu Tony Lazzeri, altro nativo di San Francisco e figlio di immigrati. Dal 1926 al 1937 fu il seconda base titolare dei grandi New York Yankees, che vinsero cinque World Series, e uno dei giocatori più popolari del baseball. Di Lazzeri si parlerà più avanti.

Negli anni Trenta la partecipazione degli italoamericani alle Major League aumentò vertiginosamente, con almeno 54 debuttanti. Alcuni fecero brevi apparizioni, ma molti ebbero una lunga carriera e due - Joe DiMaggio ed Ernie Lombardi - sarebbero stati inseriti nella Hall of Fame del baseball.

Questo afflusso senza precedenti scatenò una risposta altrettanto senza precedenti da parte dei media, che trattarono il loro arrivo con un atteggiamento ambiguo, non diverso da quello che aveva accolto gli immigrati italiani dalla fine del XIX secolo. Alcuni videro il crescente numero di giocatori italiani come una minaccia al tradizionale dominio dei giocatori irlandesi, richiamando così le tensioni etniche che erano esistite a lungo tra questi due gruppi.

Nel 1934 l'editorialista sportivo del Boston Globe Gene Mack scrisse che "gli spaghetti potrebbero presto diventare il piatto nazionale del gioco nazionale. Cuccinello, Puccinelli, Crosetti, Lazzeri, Bonura, Orsatti, DiMaggio e una miriade di altri "Wops che spaccano" non possono sbagliarsi. Gli italiani sono in questo settore per restare". L'illustrazione di accompagnamento raffigurava 13 giocatori di baseball seduti attorno a un tavolo con una grande ciotola con la scritta "spaghetti".

Tra i giocatori che esordirono negli anni Trenta, Lombardi, DiMaggio, Dolph Camilli e Phil Cavarretta furono i primi italoamericani a vincere il Most Valuable Player Award.

Fu negli anni successivi alla Seconda Guerra Mondiale che gli italoamericani raggiunsero l'apice del successo nel baseball. A quel tempo New York City era il centro dell'universo del baseball. Tra il 1947 e il 1958, gli Yankees vinsero dieci campionati e otto World Series, i Dodgers sei campionati e una Series, mentre i Giants vinsero due campionati e una Series.

I giocatori di origine italiana ricoprirono ruoli chiave in tutte e tre le squadre di New York, raggiungendo una visibilità e un'importanza senza precedenti. Tra questi ci sono: Joe DiMaggio, Yogi Berra, Phil Rizzuto, Vic Raschi e Billy Martin (Yankees); Roy Campanella, Carl Furillo e Ralph Branca (Dodgers); Sal Maglie e Johnny Antonelli (Giants). DiMaggio, Rizzuto, Berra e Campanella vinsero il premio MVP e finirono nella Hall of Fame.

Negli anni successivi alla Seconda Guerra Mondiale, l'uso di epiteti etnici è gradualmente diminuito. Ma questo non significava che non ci fossero più pregiudizi. L'Hall of Famer Joe Torre, nato nel 1940, mi ha raccontato: "Quando stavo crescendo chiedevo a mia madre: "Di che nazionalità siamo?". Lei mi rispondeva: "Sei americano". Ho percepito che a quei tempi, se non eri americano, avevi qualcosa di cui vergognarti".

Con il passare degli anni, i giocatori di seconda e terza generazione di origine italiana avevano sempre più probabilità di essere figli di matrimoni misti, di avere poca o nessuna familiarità con la lingua italiana e di considerarsi, prima di tutto, "americani".

Questo non significa che i tifosi italoamericani non riconoscessero e non celebrassero stelle come Rocky Colavito, Tony Conigliaro, Rico Petrocelli, Joe Torre e Ron Santo. Tuttavia, i media erano molto meno propensi a prendere nota dell'origine etnica di un giocatore e, col passare del tempo, i giocatori erano meno propensi a identificarsi come italoamericani.

Oltre alle dieci persone identificate sopra come membri della Hall of Fame del baseball, ci sono altre tre persone inserite più di recente.

Nativo di Seattle, Ron Santo ha superato numerose sfide, tra cui la diagnosi di diabete all'età di 18 anni, per forgiare una carriera da Hall of Fame. Nei suoi 14 anni (1960-73) come terza base dei Chicago Cubs, è stato nove volte All-Star. Dopo il suo ritiro, nel 1990 divenne un'analista per le trasmissioni radiofoniche dei Cubs, posizione che mantenne fino alla sua morte, avvenuta nel 2010 all'età di 70 anni. Nel 2003 i Cubs hanno ritirato il suo numero di uniforme 10 e nel 2011 hanno eretto una sua statua fuori dal Wrigley Field.

Le complicazioni del diabete hanno portato a diversi interventi medici nell'ultimo decennio della sua vita, tra cui l'amputazione di entrambe le gambe sotto le ginocchia. In quegli anni ci incontravamo spesso quando i Cubs venivano a Milwaukee e, nonostante le sue numerose afflizioni, non ha mai perso il suo atteggiamento positivo e il suo senso dell'umorismo autoironico. Nel 2012 è stato eletto postumo nella Hall of Fame.

Gli altri due Hall of Famers di origine italiana (John Smoltz e Craig Biggio) sono stati entrambi inseriti nel 2015.

John Smoltz è stato uno di quei rari lanciatori che hanno eccelso sia come titolare che come sostituto. Ha militato negli Atlanta Braves per i primi 20 anni dei suoi 21 anni di carriera (1988-2008). Nei primi 12 anni è stato titolare, vincendo il Cy Young Award come miglior lanciatore della National League nel 1996. Nel 2002 è diventato il "closer" dei Braves, guidando la lega con 55 "salvezze". Nel 2005 è tornato alla rotazione dei lanciatori titolari, ottenendo un record di 44-24 nelle tre stagioni successive. Otto volte All-Star, ha guidato due volte il campionato in vittorie.

Di origini italiane da parte di madre, ha raccontato della nonna materna, che accendeva candele e pregava ogni volta che lanciava: "Era un'italiana purosangue, la più grande cuoca del mondo, e le volevo un bene dell'anima".

Craig Biggio è stato un'anomalia nell'era dei free agent del baseball, avendo trascorso la sua intera carriera ventennale (1988-2007) con una sola squadra, gli Houston Astros. Ma all'interno di quella squadra è stato un giocatore straordinariamente polivalente. Nelle prime quattro stagioni è stato due volte All-Star come ricevitore. Passò poi alla seconda base, dove fu All-Star in cinque delle sue prime sei stagioni e vinse quattro Gold Glove Award. Poi, dopo 11 anni in seconda base, ha fatto un'altra transizione senza problemi giocando a centrocampo.

I suoi colpi non sono stati meno impressionanti delle sue prestazioni in campo. Nel 2007 è diventato il 27° giocatore nella storia della Major League a registrare 3.000 battute, ed è l'unico a raggiungere tutti questi traguardi: 600 doppi, 250 fuoricampo e 400 basi rubate. Gli Astros gli hanno eretto una statua fuori dal Minute Maid Park nel 2003 e hanno ritirato il suo numero di uniforme 7 nel 2008.

Quando parlai con Biggio nel 2005, gli chiesi cosa lo spingesse a continuare a giocare dopo 18 stagioni. "Solo il gioco in sé", mi disse. "Si può competere con i migliori giocatori del mondo, e questo mi sta molto a cuore".

Gli italoamericani del baseball si sono fatti notare anche fuori dal campo...

Sì. Se è vero che negli ultimi decenni del XX secolo un numero minore di giocatori di origine italiana entrava in serie A, allo stesso tempo si assisteva a una mobilità ascendente nel baseball, con l'ingresso in posizioni dirigenziali, come manager sul campo, dirigenti del front office e proprietari. Dal 1981, ad esempio, dieci manager, tre dei quali (Tommy Lasorda, Tony La Russa e Joe Torre) sono nella Hall of Fame, hanno portato le loro squadre a un totale di 24 World Series, vincendone 15. Torre è stato anche nove volte All-Star come giocatore e ha ricoperto il ruolo di direttore operativo della Major League Baseball dal 2011 al 2020. Inoltre, nel 1989, un italoamericano è stato nominato alla massima carica del gioco, quella di Commissario del Baseball.

Credo che nessuno meglio di A. Bartlett ("Bart") Giamatti incarni l'evoluzione e l'importanza sociale degli italoamericani nel baseball e nella società americana. Suo padre, figlio di immigrati, ha conseguito un dottorato di ricerca ad Harvard ed è stato professore di italiano al Mount Holyoke College di South Hadley, Massachusetts. Nato nel 1938, Bart era appassionato di baseball e ha tifato per tutta la vita per i Boston Red Sox.

Dopo aver conseguito il dottorato, ha insegnato letteratura comparata a Yale, dove si è fatto una solida reputazione sia come insegnante che come studioso di letteratura rinascimentale, concentrandosi sull'influenza degli scrittori italiani del Rinascimento sulla letteratura inglese. Poi, nel 1978, nella stessa città in cui il nonno immigrato aveva lavorato in una fabbrica, è stato nominato presidente di Yale all'età di 39 anni, il più giovane ad aver mai ricoperto tale carica.

Nel 1986 lasciò l'incarico in una delle più prestigiose università americane per diventare presidente della Major League Baseball. Aveva catturato l'attenzione dei dirigenti della Major League scrivendo in modo eloquente sul ruolo del baseball come gioco americano per eccellenza.

Poi, il 1° aprile 1989, fu nominato settimo commissario della Major League Baseball. Nel giro di due generazioni, il nipote di un immigrato italiano era salito al vertice del gioco nazionale americano. Non avendo il talento per giocare, Giamatti trovò un altro modo per realizzare il sogno di diventare un giocatore della Major League che condivideva con molti della sua generazione.

Purtroppo morì sei mesi dopo, vittima di un attacco cardiaco all'età di 51 anni. Ma anche se ebbe poche possibilità di dimostrare ciò che avrebbe potuto realizzare, il suo amore per il gioco, dimostrato sia nella difesa delle sue tradizioni sia nelle sue eloquenti celebrazioni del suo significato, fu sufficiente a convincere molti del suo status. L'editorialista del New York Times Ira Berkow ha ipotizzato che Giamatti, "quest'uomo coltissimo e civile, caloroso e generoso e spiritoso... sarebbe potuto diventare il miglior commissario di baseball che abbiamo mai avuto. Aveva cervello, forza d'animo e i migliori desideri del gioco".

Per Giamatti, il fan per eccellenza che vedeva nel gioco che amava una chiara espressione dello spirito nazionale, il baseball divenne un'espressione metaforica del Sogno Americano, non come appagamento materiale ma come ricerca spirituale della casa. In effetti, il significato del suo impatto sul baseball non è solo quello di essere salito alla massima carica, ma anche quello di esserne stato uno degli esponenti più appassionati e articolati. Capì meglio di molti altri la natura e il significato dell'esperienza degli immigrati e ne scrisse in modo eloquente. "Il ritmo di base del baseball", scrisse, "l'uscita e la successiva ricerca del ritorno a casa, fa parte della trama della storia della nostra vita nazionale, la storia di quanto sia difficile trovare le origini di cui si ha tanto bisogno. Il concetto di casa ha una risonanza particolare per una nazione di immigrati, che hanno tutti lasciato una casa per cercarne un'altra".

Alcuni degli individui ritratti in Beyond DiMaggio hanno trovato fama e fortuna inimmaginabili giocando a baseball. La maggior parte ha trovato un successo più modesto. Ma tutti avevano una cosa in comune, oltre al loro retaggio etnico: si guadagnavano da vivere praticando la quintessenza del gioco americano, un gioco che per molti era il simbolo stesso dei valori e delle promesse del Paese in cui i loro antenati erano immigrati.

Perché Joe DiMaggio, più di ogni altro, è diventato il simbolo di questi talentuosi giocatori di baseball italoamericani?

Uno degli uomini più riconoscibili e popolari dell'America della metà del XX secolo, Joe DiMaggio è stato celebrato nella musica e nella letteratura come un eroe iconico. Dopo la sua morte, avvenuta nel 1999, la Camera dei Rappresentanti degli Stati Uniti ha approvato una risoluzione che lo onora "per la sua storica carriera nel baseball; per i suoi numerosi contributi alla nazione durante la sua vita; e per aver trasceso il baseball ed essere diventato un simbolo per i secoli del talento, dell'impegno e dei risultati".

Ma prima di tutto Joe DiMaggio era un giocatore di baseball. È stato il leader indiscusso delle squadre dei New York Yankees che hanno vinto nove titoli delle World Series nei suoi 13 anni di carriera, dal 1936 al 1951, con tre anni persi per il servizio militare nella Seconda Guerra Mondiale. È stato tre volte il Most Valuable Player dell'American League e detiene quello che molti considerano il record più notevole di tutto il baseball, una striscia di battute di 56 partite nel 1941. Figlio di immigrati, era l'incarnazione del sogno americano.

Agli occhi dei suoi contemporanei, Joe DiMaggio era universalmente considerato il miglior giocatore che avessero mai visto. Persino il suo acerrimo rivale, Ted Williams, disse che "era il più grande giocatore di baseball del nostro tempo. Poteva fare tutto". Per l'ex governatore di New York Mario Cuomo, la vita di DiMaggio "ha dimostrato a tutti i lottatori e i esploratori, come me, che l'America avrebbe dato spazio alla vera eccellenza, indipendentemente dal colore, dall'accento o dall'origine".

Uno di quei rari atleti che trascendono il mondo dello sport, DiMaggio è stato definito da più di uno scrittore l'ultimo eroe americano. Quando morì, il suo status duraturo di icona culturale fu confermato da un'ondata di adulazione che poche figure pubbliche, in qualsiasi ambito della vita, erano in grado di evocare. La sua morte finì in prima pagina su tutti i principali quotidiani e fu ampiamente trattata nei telegiornali e negli speciali televisivi. Come ha detto un abitante di Brooklyn, DiMaggio "ha incarnato un'epoca in cui, per molti di noi, il baseball era la cosa più importante della vita".

Anche due dei fratelli di Joe hanno ottenuto record impressionanti nella Major League. Vince, il più grande dei tre e, come Joe, un esterno centro, è stato due volte All-Star in dieci anni di carriera. Dom, il più giovane, è stato sette volte All-Star come esterno centro per i Boston Red Sox. Ho avuto l'opportunità di incontrare Dom nel 2002, quando è stato invitato all'All-Star Game di Milwaukee. Non solo ha accettato la mia richiesta di intervistarlo, ma mi ha anche invitato a sedermi con lui nel settore VIP dell'All-Star Game. Di tutti i giocatori della Major League che ho incontrato nel corso degli anni, nessuno è stato più coinvolgente, intelligente ed eloquente di Dom. Gli sarò sempre grato per aver accettato di scrivere la prefazione di Beyond DiMaggio.

Prima di Joe DiMaggio, c'era Tony Lazzeri, come dice il suo ultimo libro: "Tony Lazzeri: Yankees Legend and Baseball Pioneer". Ci parli di lui, per cortesia

Ammetto che prima di lavorare a Beyond DiMaggio sapevo ben poco di Tony Lazzeri, se non che era un seconda base della Hall of Fame nelle grandi squadre degli Yankees degli anni Venti e Trenta. Quando ho saputo che era uno dei più celebri giocatori di baseball della sua epoca, mi sono sentito come se avessi scoperto un tesoro sepolto e ho deciso di impegnarmi per restituirgli il posto che gli spetta nella storia del baseball.

Nei 12 anni in cui giocò per i New York Yankees (1926-37), in un'epoca in cui il baseball dominava il mondo dello sport ed era un'importante istituzione sociale, Tony Lazzeri ne fu una delle più grandi stelle. Membro chiave della dinastia degli Yankees, che in quell'arco di tempo vinse sei campionati e cinque World Series, fu lodato dai suoi colleghi e dalla stampa come uno dei migliori e più intelligenti giocatori della sua epoca. Il leggendario editorialista sportivo Red Smith lo definì "il più grande giocatore mai esistito". In tutto il periodo trascorso con gli Yankees non c'è stato nessuno che abbia avuto più importanza per la squadra in termini di battute e di gioco, di impegno e di idee brillanti e rapide".

Originario di San Francisco e nato da immigrati italiani, Lazzeri fu ingaggiato dagli Yankees dopo aver realizzato 60 fuoricampo nel 1925 per i Salt Lake City Bees della Pacific Coast League, la prima volta che tale numero era stato raggiunto nella storia del baseball organizzato. La stagione successiva, il ventiduenne seconda base esordiente fu inserito nel lineup iniziale degli Yankees insieme a Babe Ruth e Lou Gehrig. Si affermò immediatamente come una stella, arrivando secondo a Ruth in RBI (punto battuto a casa - run batted in - una statistica accreditata al battitore quando la sua azione alla battuta consente alla squadra di realizzare uno o più punti ) e terzo in fuoricampo nell'American League.

Uno dei primi middle infielders a colpire con potenza, durante la sua permanenza negli Yankees è stato il terzo battitore più produttivo (dopo Ruth e Gehrig) della loro leggendaria formazione, con più punti segnati di tutti i giocatori dell'American League, tranne cinque, e più fuoricampo di tutti, tranne sei. Ha anche stabilito dei record che né Ruth né Gehrig hanno raggiunto; detiene ancora il record dell'American League per gli RBI in una singola partita (11) ed è stato il primo giocatore (e uno dei soli 13) a realizzare due grand slam in una sola partita.

Inoltre, Lazzeri fu riconosciuto dai suoi colleghi e dalla stampa come un leader naturale che possedeva una delle più acute menti di baseball della sua epoca. Anche da esordiente, fu riconosciuto come il capitano de facto della squadra. Frank Crosetti, suo compagno di squadra dal 1932 al 1937, disse: "Non era solo un grande giocatore, era un grande uomo. Era un leader. Era come un manager sul campo". Sebbene Lazzeri fosse notoriamente silenzioso, aveva uno spiccato senso dell'umorismo; i suoi scherzi negli spogliatoi lo rendevano simpatico ai compagni di squadra. I suoi colpi, la sua capacità di leadership e il suo atteggiamento modesto lo resero anche uno dei preferiti dai tifosi degli Yankee, secondo per popolarità solo a Babe Ruth.

Ciò che rende i suoi risultati ancora più notevoli è che giocò per tutta la carriera mentre era affetto da epilessia, una condizione talmente stigmatizzata all'epoca da essere tenuta segreta ai fan. Con il tempo, però, i suoi successi furono oscurati da quelli dei suoi iconici compagni di squadra Ruth e Gehrig e divenne una figura trascurata.

Ma a mio avviso, ancor più che per le sue imprese di baseball, Lazzeri merita di essere ricordato per il suo impatto sociale come prima grande star di origine italiana nella Major League Baseball. La sua fama e la sua popolarità nel passatempo nazionale instillarono nei suoi connazionali un ritrovato senso di orgoglio. Simbolo delle loro speranze di trovare una casa in una nuova terra non sempre accogliente, divenne rapidamente un eroe che fu onorato in diverse città. A seguito di un evento del 1927 a New York, a cui parteciparono più di 1.000 persone, il New York Times riportò che "nella grande sala da ballo risuonavano discorsi che lodavano il brillante lavoro del popolare infielder e la sua condotta esemplare fuori e dentro il campo".

Il suo fascino fu tale da ispirare una generazione di immigrati precedentemente scettici e disinteressati a legarsi al baseball. Per la prima volta gli italoamericani si affollarono nei campi da gioco, alcuni sventolando bandiere italiane, per fare il tifo per la giovane stella.

È difficile, credo, sopravvalutare l'impatto di Lazzeri nel contrastare le immagini negative degli italiani. Con il suo atteggiamento modesto, la sua forte etica del lavoro e la sua leadership silenziosa, era l'antitesi di tutti gli stereotipi che si erano radicati nella coscienza pubblica per decenni. È possibile che, in un periodo di copertura mediatica del baseball senza precedenti a livello nazionale, abbia fatto più di chiunque altro prima di lui per migliorare la percezione pubblica degli italoamericani. Data la sua natura modesta e senza pretese, questo non era chiaramente un ruolo che cercava, ma ha dimostrato di essere la persona giusta al momento giusto per ricoprirlo.

Ultimamente il baseball italiano è tornato sotto i riflettori grazie a Mike Piazza, uno dei più grandi campioni della storia recente del baseball, che ora allena la Nazionale italiana e ha portato diversi giocatori e prospetti italoamericani con la maglia azzurra della Nazionale. We the Italians è media partner della Federazione Italiana Baseball e Softball e abbiamo avuto l'onore di assegnare a Mike il premio "Two Flags One Heart" in occasione del nostro gala del 2022...

Non sorprende che più ci si allontana dalla generazione degli immigrati, meno è probabile che gli individui abbiano un forte senso di identità etnica. I giocatori la cui carriera è iniziata negli anni Settanta e oltre hanno espresso ancora orgoglio per le loro origini italiane e alcuni hanno espresso rammarico per non aver imparato a parlare italiano, ma è più probabile che si considerino "americani". Ma c'è anche chi mantiene un forte senso di identità etnica.

Nessuno dei giocatori più giovani che ho incontrato mi ha colpito più di Mike Piazza. 12 volte All-Star in 16 anni di carriera, detiene il record del maggior numero di fuoricampo per un ricevitore (396) e per dieci volte ha superato i 300 punti. Ampiamente considerato il miglior catcher offensivo di sempre, è stato inserito nella Hall of Fame nel 2016. Eppure, per tutti i risultati raggiunti, l'ho trovato straordinariamente umile. Mi ha colpito anche la sua consapevolezza e il suo impegno genuino nei confronti delle sue origini italiane.

Piazza è stato a lungo coinvolto negli sforzi per promuovere lo sviluppo del baseball in Italia. Ha fatto parte del Team Italia nei primi tre World Baseball Classics, come giocatore e allenatore, e ora è il manager della nazionale italiana. L'ho incontrato per la prima volta nel 2006, quando era la stella della Squadra Italia nel World Baseball Classic inaugurale. Vedendolo giocare con tanto entusiasmo e gioia, era evidente che non era lì per la gloria personale, ma per l'orgoglio di rappresentare il Paese in cui sono nati i suoi nonni. "Non me lo sarei perso per nulla al mondo", mi disse all'epoca. "È importante ricollegarsi alle proprie radici".

Ho avuto modo di parlare con lui altre volte quando la sua squadra veniva a Milwaukee per giocare contro i Brewers. Ogni volta mi ha impressionato per la sua conoscenza della storia degli italoamericani nel baseball. Nel 1997 ebbe una media battuta di .362, il suo massimo in carriera. Incredibilmente, fu sufficiente per il terzo posto nella lega. "Volevo davvero essere il primo catcher dopo Ernie Lombardi a vincere il titolo di battitore [nel 1938 e nel 1942]", mi ha detto.

Nel 2002 ha fatto il suo primo viaggio in Italia, dove, nell'ambito dello sforzo della Major League Baseball di internazionalizzare il gioco, ha condotto degli stage per i giovani giocatori italiani. "Da allora sono tornato diverse volte", mi ha detto. "Ho sempre cercato un ponte tra gli italiani che sono rimasti e quelli che sono emigrati qui. Siamo cresciuti negli Stati Uniti e amiamo questo Paese, ma siamo molto orgogliosi delle nostre origini, del fatto che l'Italia è un Paese di tradizione storica. È questo che trovo affascinante".