There is an extraordinary description of Made in Italy as seen from the perspective of design in the book “Il design e l'invenzione del Made in Italy” (Design and the Invention of Made in Italy) by Professor Elena Dellapiana.

It is a theme that intersects with the United States several times, even in the introduction of the "Made in Italy" brand, which before being made official in Italy was requested to Italian manufacturers by American department stores, aware of its strength and importance. We are pleased and grateful to Prof. Dellapiana to be able to offer our readers this interview.

Dear Professor, thank you for agreeing to be our guest on We the Italians. Your book is enlightening. I would propose for our interview to follow at least part of its table of contents. The first chapter is entitled "Alle origini dell'identità nazionale: Rinascimento e artigianato” (At the origins of national identity: Renaissance and craftsmanship)...

The first thing concerns chronology, because when talking about Design and Made in Italy, the one most agreed upon refers to the postwar period, that is, the 1950s, with a few exceptions regarding the interwar period.

I wanted to try to shift my focus to the moment of the formation of the nation-state, and so I also tried to explore how, before Italian political unity, the various states that made up Italian culture measured themselves against the theme of product, both high craft and initially industrial, and how these were presented on international stages, the great expositions, starting with the most important being the Great Exhibition in London in 1851.

In this context, I verified that the most recurring key words are two terms that then recur throughout the narrative until the late 1980s. The first word is "Renaissance," which is somewhat the blanket under which almost all Western or Westernized countries position themselves, sharing the idea that it is a period of reference above all for the interpretation of that phase, not so much as a moment of the great Renaissance geniuses, but as a moment of great diffusion and fortune of the so-called artistic workshops. This corresponds to a historiographical invention, because the term "Renaissance" is precisely a historiographical invention of the first half of the nineteenth century, which is due to art historians such as Michelet and Burckardt.

It is a time when creativity takes over a little bit in all areas, not only those of high art but also those of applied art, decorative arts and therefore as close to our themes, that is, those of the product, of commodities: because we must not forget that in universal exhibitions, commodities are exhibited, with all that euphoria typical of the second industrial revolution.

The other word, which is more specifically Italian, because all historians agree in identifying Italy and especially the Florence of the Medici as the cradle of this phenomenon, is "craftsmanship."

Handicrafts, from the quality of materials to semi-finished and then finished products, is the sector that both international critics and those in the various national delegations place the most in the Italian peninsula.

And so that formula of “bello, buono e ben fatto” (beautiful, good and well made), which is a very contemporary formula of the rhetoric of promoting Made in Italy, is found in an absolutely fulfilled way as early as the second half of the 1800s.

Continuing the historical journey, we come to the 20th century... “L'italianità costruita dall'interno: gli anni del regime, la retorica del fatto a mano”(Italian-ness built from within: the years of the regime, the rhetoric of the handmade)

The fascist regime has always played on certain ambiguities consciously and with communication skills as exceptional as they are disturbing. In its multi-facetedness, it inherits the formula of "handmade" from the late nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, and applies this same formula with a series of equations, whereby from the artistic Renaissance through the Risorgimento it moves to the process of Italian Unification and then to Fascism. Fascist intellectuals supported by the regime argue that there is this sequence of historical and cultural periods worthy of unification, and from there the promotion of production in Italy develops.

During the twenty years of Fascism, on the one hand there is a great promotion with very important state financial interventions for a very small number of large industrial enterprises with family-run characteristics, and on the other hand there is the promotion of production districts with an artisan or semi-mechanized character.

This is the period of origin of many Italian institutions, which are still in existence, set up for the promotion of handicrafts and small and medium-sized enterprises, such as the Istituto per il Commercio Estero (Institute for Foreign Trade), and the Ente Nazionale delle Piccole Imprese, which then in fact became the Confederazione Nazionale dell'Artigianato e della piccola e media impresa (National Confederation of Handicrafts and Small and Medium Enterprises). These institutions carry out propagandistic promotion by always linking the formula of "beautiful, good and well made," the legacy of Italy's glorious artistic tradition (especially applied decorative arts) to the policies on corporatism that affected the entire professional world, not just the manufacturing world, during Fascism.

It was in these years that the idea of Made in Italy began to develop, especially from the request of external buyers. Some privileged channels, the most important of which is the United States of America, see buyers in department stores asking manufacturers, although there is no specific legislation yet, to brand their products “Made in Italy”.

And so the phase of Fascism is the one that reinforces from a regulatory and promotional point of view what Made in Italy is today, and Design enters this field in a timely way. The promotion is in some cases aimed at what is in the field of mass production in Italy at that time, so the micromechanical companies, such as typewriters. Olivetti is promoted so much abroad, and the exhibitions promoted during Fascism are interesting because they present families of objects: typewriters and calculating machines, or Lenci dolls, which are then the ancestors of Barbie dolls, or even everything related to preserved food, wines, oil.

Let me please interrupt the thread of the book's chapters for a moment. Please help our readers understand even better two relationships you describe: that between folklore and local tradition of the many different areas that make up Italy and the international context; and that between entrepreneurship and culture, which is particularly strong in our country.

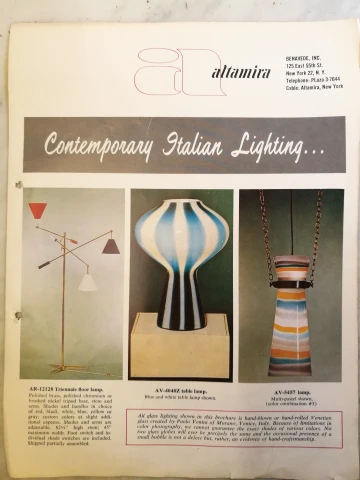

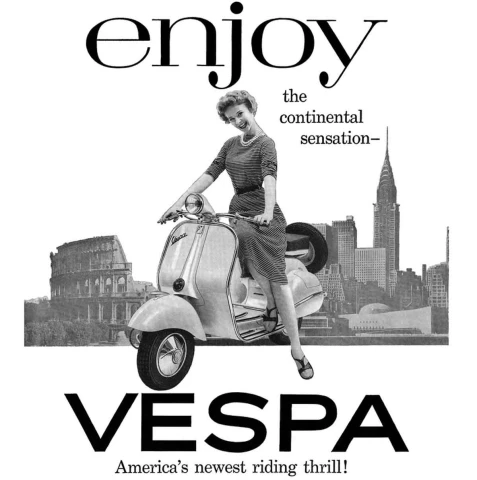

In the international context, it is above all America that sees privileged relations with Italy, also little conditioned by political events. During the years of Fascism, there is a strong community of Italians, naturalized or in the process of naturalization or exiles, who obviously promote a politically very different idea of Italy, also through its cultural products. I am thinking of Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti and the group that would later go on to found the House of Italian Handicrafts in New York, an entity active since 1943, which brought to the United States a new image of Italy and its artistic culture and explored all its sectors. In the exhibits at the House of Italian Handicrafts and in the spinoffs in the department stores there are references to the craftsmanship of the Mediterranean and thus to this very powerful and very seductive category that serves to revive the transatlantic shipping lines, and to this perception that is la bella vita, what will then quickly become la dolce vita, which by the way is a concept that the ancient Romans invented.

There is also the presentation of products that are closer to North American production, so furniture, glass, textiles, but different because the Italian ones respond to a similar taste but are much more handmade, are much more accurate, and are customizable.

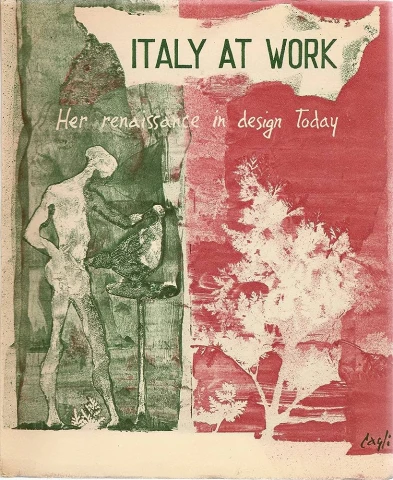

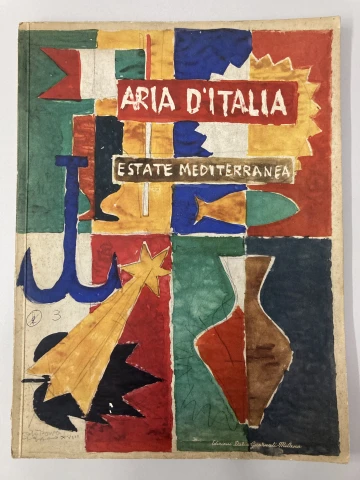

So the choice is precisely a path that pursues a strong Italian-ness, and this in some cases is promoted by local communities. The typical example is the very famous exhibition "Italy at Work: her Renaissance in Design Today," which tours 13 museums in the United States between 1950 and 1953: it is organized by the Brooklyn Museum, home to a sizeable Italian American community, financed through crowdfunding, and promoted through theatrical performances, including Pirandello's last play, then mixing, in a typically North American formula, benefit galas with high culture events and trade fairs.

Italian Americans take this North American formula and use it to promote Italy with a certain language that strikes a balance between what the foreign buying public expects and what can be given, so there are minor adjustments depending on the context. Italian Americans are a very powerful means of amplification.

Please remind us about the great impact on Made in Italy of the three events held in the United States in 1972, 1981 and 1989

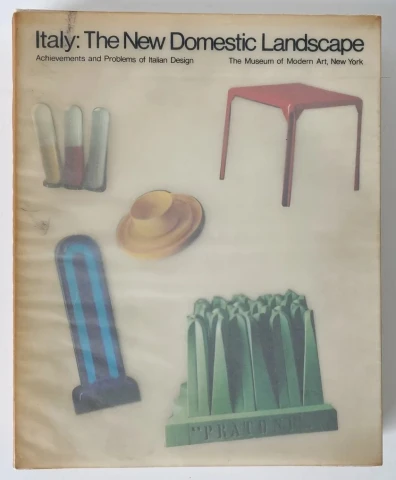

The 1972 exhibition promoted by MOMA is still to this day the most expensive ever organized by this institution, and the largest in terms of financial investment, almost all of which came from Italy and from very important institutions and companies ranging from the Foreign Trade Institute to Alitalia, from FIAT to IRI, and then a whole series of entrepreneurs in the furniture, food, and mechanical industries. So there is a lot of financial commitment on the part of all the players on the Italian scene and a lot of curatorial commitment that is due to a young Argentine architect who was the new head of the architecture and design department at Moma, Emilio Ambasz.

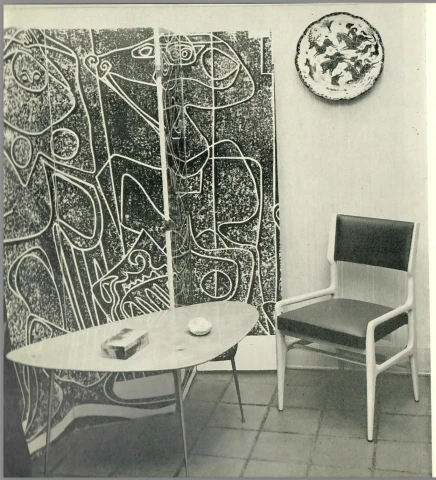

This exhibition is a huge success with the public and also arouses much controversy. It contains a collection of about 250 pieces of Italian design since the 1950s under the title "The New Italian Landscape: Problems and Achievements of new Italian Design": all the companies are presented in showroom form, there are showcases on the MOMA terrace.

And then instead, there are 11 environments, as if they were period rooms, entrusted to architects and designers (at that time the division was not so clear-cut in Italy) who belong to various categories. Some propose living systems related to themes such as transformability and nomadism, very American themes that here in Italy was actually heard very little but instead found much favor with the American public. Then there is a group of young designers who belong to the radical culture of '68, which obviously influences all of Italy and the whole world, who instead propose very political positions, very related to the struggle for housing and employment.

The exhibition catalog also has a series of essays that touch on the issues of economics and politics, but the American public especially picks up on the great fascination with imaginative objects, off the beaten path compared to the North American mainstream, and there is a consecration of this cliché of the creativity of sprezzatura, a term little used in Italy but very much in vogue in America, just with the word in Italian. The American public is enthusiastic, and there is a great consecration of Made in Italy that can also be traced back to the overlap between architecture and design, which was a much less common thing in the United States.

Aspen, on the other hand, has been a series of conferences devoted to design since 1951 that aims to bring business and creativity together. In the 1980s it was decided to dedicate "monographic" conferences to certain countries: Italy is the only one to which two editions are dedicated, in 1981 and 1989. In the first edition of 1981 there is already an opening to many disciplines not strictly related to design as we understand it, that is, to the object, because we already start talking about cinema, music, cooking. The difference between the '81 conference and the '89 conference is the world political and economic conjuncture. In '89 the picture is of a world in which the Cold War ends and Reaganomics begins : food is already glocal, then there is fashion, all the designers, all the architects. The conference has a huge success, although of course Aspen in Colorado is much less reachable and attended than MOMA in New York.

Aspen enshrines the evolution of Made in Italy that is no longer only related to the brand, but that conveys atmospheres, philosophies of life, categories that are much less palpable, but perhaps even more powerful in some ways, and is very successful especially in the North American market, because there are the possible buyers who also have the means to buy expensive things, before the advent of the Middle East and the Far East. Moreover, the American one is the market most ready to absorb foreign traditions, which in our case anyway belong to the DNA of a long migratory flow and also of great fortunes of Italian American communities. In this sphere, another word that goes so much to describe Italy in America is "cordial": for example, the beauty of Italian ladies is cordial, less algid than French ladies, it is refined but not distant.

The expression "Made in Italy" describes Italy without using Italian language... still speaking of Made in Italy, please tell us from a historical, cultural and business perspective, the specific relationship with the United States, the subject of the chapter “Italy Creates: gli Stati Uniti dal Piano Marshall a Italy at Work” (Italy Creates: the United States from the Marshall Plan to Italy at Work)…

The Marshall Plan helps Made in Italy just as it helps Made in Germany, Made in France, Made in Japan, and in this sense the kind of policy is equivalent; from the technical point of view it is the same a little bit for all of them, also because the goal is to provide financial and organizational tools especially in terms of defense against the red danger.

What has happened for Made in Italy compared to other countries is again the ability of Italians to adapt the environment more in their favor, moreover not in all sectors. Evidently this goal in Italian heavy enterprise has not materialized in an obvious way, however, it has done so in the world of design, traditional production centers and medium-sized enterprises, which are favored by the Marshall Plan because they do not compete with American big business in the field of goods production.

Well, in this field, this magical alchemy (which has never been repeated) of alliance between designers and industrialists, who are willing to experiment a great deal even taking risks, has the ability to obliterate to some extent the ideological-political component that is clear in North American programs, and to restore something that continues to be the dolce vita, the ability to make do.

It is a bit like the formula coined by a very important American designer, George Nelson, who had been in Italy with a fellowship precisely related to the exchanges, including cultural ones, of the Marshall Plan: "Blessed are the poor," which recounts a poetics in which the money of the Marshall Plan is used with great communicative ability and without flattening itself to what was being configured as the "irresistible empire," according to the happy definition of historian Victoria de Grazia.

Made in Italy is reinforced because the Marshall Plan interventions, especially in the field of small and medium enterprises, are declined in a way that pleases everyone, they are not highly politicized, they are de-ideologized. This is the winning formula so that later we can get to the MOMA exhibition, -where political content comes in, but that definitely takes a back seat.

The next chapter of his book also has to do (also) with the United States: it is titled “La terza via del Made in Italy: il caso Olivetti” (The third way of Made in Italy: the Olivetti case)...

The Olivetti case is a subject on which thousands of pages continue to be written because it is a case study of extraordinary interest in many different aspects. From as early as Camillo Olivetti's legendary trip to the United States to visit Henry Ford's factory, the company imported North American production models and began to compete with the large typewriter and computing machine manufacturers.

Dino Olivetti, Adriano's younger brother, spent his entire life in the United States. In the early 1950s, first with the headquarters, then with the showroom in New York and later in Chicago and other North American cities, typewriters were proposed, with a method that was very much praised by the Americans for both formal and organizational aspects. In Aspen it is said that "IBM should learn from the Olivetti business model, because of welfare, because of the inclusion of designers, because of communication."

However, when Olivetti then tries to enter the U.S. electronics market, problems begin, because after some time it is now fairly well established that failure in this area, despite the installation of Olivetti study and information centers in the U.S., depended heavily on interference from large American electronics companies.

Also in this sense there is a very interesting exchange among collectors, enthusiasts. Owning an Olivetti letter 22 is still a status symbol, because it represents that quality of the Italian product that is at the same time technological but looks like a sculpture: this is the word that recurs most frequently in North American reviews of Olivetti production.

Finally, I ask your opinion on a curious circumstance, which I believe is unmatched anywhere else in the world. Taking for granted the cultural and anthropological difference of the two peoples, what do you think about the fact that in America the expression "Italian style" very often has a positive meaning, referring to luxury, attention to detail and talent, while we in Italy use the equivalent "all’italiana" almost always with a negative and opposite value to that used in America?

I try to give an answer as a historian, albeit at the risk of generalizing. In the many, many articles devoted to Italy especially in the immediate post-World War II period by the American press, one thing that is always evoked - in addition to the already mentioned "Blessed are the Poor" - is that Italians have a big ability to make do, and to achieve excellent results with little from the point of view of resources but with a little cunning and with adaptability, with creativity being recounted as a dowry, a quality.

The line between quality and negativity is wafer-thin, so viewed from afar Americans say, "look how they managed to get by and get great results," sometimes not knowing exactly what is behind it. Those of us who are more inside and therefore know more about the mechanisms and how those clevernesses often mean circumventing norms, if not outright breaking them, give a different description, perhaps exaggerating the negative aspects.

So it seems quite obvious to me that the ability to be reborn (there is an article by an American writer who says that Italians are like a phoenix, always capable of rebirth from their own ashes), seen from afar has one flavor, a bit heroic, seen from the inside can have a whole other flavor.

E’ una straordinaria descrizione del Made in Italy visto dal punto di vista del design, quella contenuta nel libro “Il design e l'invenzione del Made in Italy” della Professoressa Elena Dellapiana.

E’ un tema che si incrocia più volte con gli Stati Uniti, persino nell’introduzione del brand “Made in Italy”, che prima di essere reso ufficiale in Italia viene richiesto ai produttori italiani dai department stores americani, consapevoli della sua forza e della sua importanza. Siamo lieti e grati alla Prof.ssa Dellapiana di offrire ai nostri lettori questa intervista.

Gentile Professoressa, la ringrazio per aver accettato di essere ospite di We the Italians. Il suo libro è illuminante. Proporrei per la nostra intervista di seguirne almeno in parte l’indice. Il primo capitolo si intitola “Alle origini dell'identità nazionale: Rinascimento e artigianato”…

La prima cosa riguarda la cronologia perché parlando di Design e Made in Italy, quella più condivisa fa riferimento al dopoguerra, cioè agli anni ‘50, con qualche eccezione relativamente al periodo fra le due guerre.

Io ho voluto provare a spostare il mio focus sul momento della formazione dello Stato Nazionale, e quindi ho cercato di esplorare anche come prima dell’unità politica italiana i vari stati che componevano la cultura italiana si sono misurati con il tema del prodotto, sia di alto artigianato sia inizialmente industriale, e come questi siano stati presentati sui palcoscenici internazionali, le grandi esposizioni, partendo dalla più importante che è la Great Exhibition di Londra del 1851.

In questo contesto ho verificato che le parole chiave più ricorrenti sono due termini che poi si ritrovano nel corso di tutta la narrazione fino alla fine degli anni ‘80 del secolo scorso. La prima parola è “Rinascimento” che è un po’ la coperta sotto la quale si posizionano quasi tutti i Paesi occidentali o occidentalizzati, condividendo l’idea che sia un periodo di riferimento soprattutto per l’interpretazione di quella fase, non tanto come momento dei grandi geni rinascimentali, quanto come momento di grande diffusione e fortuna delle cosiddette botteghe artistiche. Questo corrisponde a una invenzione storiografica - perché il termine “Rinascimento” è appunto un’invenzione storiografica della prima metà dell’Ottocento, che si deve a storici dell’arte come Michelet e Burckardt.

È un momento in cui la creatività prende il sopravvento un po’ in tutti i settori, non soltanto quelli dell’arte alta ma anche quelli dell’arte applicata, delle arti decorative e quindi quanto di più vicino ai nostri temi, cioè quelli del prodotto, delle merci: perché non bisogna dimenticarsi che nelle esibizioni universali si espongono merci, con tutta quella euforia tipica della seconda rivoluzione industriale.

L’altra parola, che è più specificamente italiana, perché tutti gli storici concordano nell’individuare l’Italia e soprattutto la Firenze dei Medici come la culla di questo fenomeno, è invece “artigianato”.

L’artigianato, dalla qualità dei materiali ai semi-lavorati e poi ai prodotti finiti, è il settore che sia i critici internazionali sia gli addetti delle varie delegazioni nazionali collocano maggiormente nella penisola italiana.

E quindi quella formula di “bello, buono e ben fatto”, che è una formula molto contemporanea della retorica della promozione del Made in Italy, si ritrova in maniera assolutamente compiuta già nella seconda metà dell’800.

Proseguendo nel percorso storico, si arriva al XX secolo… “L'italianità costruita dall'interno: gli anni del regime, la retorica del fatto a mano”

Il regime fascista ha giocato sempre su alcune ambiguità in maniera consapevole e con capacità di comunicazione eccezionale quanto inquietante. Nella sua multi-sfaccettatura, eredita la formula del “fatto a mano” dal tardo diciannovesimo secolo e dall’avvio del ventesimo, e applica questa stessa formula con una serie di equazioni, per cui dal Rinascimento artistico attraverso il Risorgimento si passa al processo dell’Unità d’Italia e poi al Fascismo. Gli intellettuali fascisti appoggiati dal regime sostengono che ci sia questa sequenza di periodi storici e culturali meritevoli di essere accomunati, e da qui si sviluppa la promozione della produzione in Italia.

Durante il Ventennio da una parte c’è una grande promozione con interventi finanziari statali molto importanti per un numero molto ristretto di grandi imprese industriali con caratteristiche di gestione familiare, e dall’altra c’è la promozione dei distretti produttivi a carattere artigianale o semi-meccanizzato. Questo è il periodo di origine di molte istituzioni italiane, ancora esistenti, nate per la promozione dell’artigianato e della piccola media impresa, come ad esempio l’Istituto per il Commercio Estero, e l’Ente Nazionale delle Piccole Imprese, che poi di fatto diventa la Confederazione Nazionale dell'Artigianato e della piccola e media impresa. Queste istituzioni effettuano un’azione di promozione propagandistica legando sempre la formula del “bello, buono e ben fatto”, dell’eredità della gloriosa tradizione artistica italiana (soprattutto delle arti decorative applicate) alle politiche sul corporativismo che investono tutto il mondo professionale, non soltanto quello produttivo, durante il Fascismo.

E’ in questi anni che si inizia a sviluppare l’idea del Made in Italy, soprattutto a partire dalla richiesta dei committenti esterni. Alcuni canali privilegiati, il più importante dei quali sono gli Stati Uniti d’America, vedono i buyers dei department stores che chiedono ai produttori, anche se non c’è ancora una normativa specifica, di marchiare “Made in Italy” i loro prodotti.

E quindi la fase del Fascismo è quella che rinforza da un punto di vista normativo e promozionale quello che è oggi il Made in Italy, e il Design entra in maniera puntuale in questo ambito. La promozione è in alcuni casi mirata a quello che c’è in quel momento in Italia nel campo della produzione di serie, quindi le aziende della micromeccanica, come le macchine per scrivere. Olivetti viene promosso tantissimo all’estero, e le mostre promosse durante il Fascismo sono interessanti perché presentano delle famiglie di oggetti: le macchine per scrivere e da calcolo, oppure le bambole Lenci, che sono poi le antenate delle Barbie dolls, o anche tutto quello che riguarda il cibo conservato, i vini, l’olio.

Interrompo per un attimo il filo dei capitoli del libro. Le chiedo di aiutare i nostri lettori a capire ancora meglio due relazioni da lei descritte: quella tra folklore e tradizione locale delle tante diverse zone che formano l’Italia e il contesto internazionale; e quella tra imprenditorialità e cultura, così forte e particolare nel nostro Paese.

Nel contesto internazionale è soprattutto proprio l’America che vede rapporti privilegiati con l’Italia, anche poco condizionati dalle vicende politiche. Durante gli anni del Fascismo c’è una forte comunità di italiani, naturalizzati o in via di naturalizzazione oppure esuli, che promuovono ovviamente un’idea politicamente molto diversa di Italia, anche attraverso i suoi prodotti culturali: penso a Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti e al gruppo che poi andrà a fondare l’House of Italian Handicrafts a New York, un ente attivo fin dal 1943, che porta negli Stati Uniti una nuova immagine dell’Italia e della sua cultura artistica e che ne esplora tutti i settori. Nelle mostre all’House of Italian Handicrafts e negli spinoff nei department stores ci sono riferimenti all’artigianato del Mediterraneo e quindi a questa categoria potentissima e molto seducente che serve a rilanciare le linee di navigazione transatlantica, e a questa percezione che è la bella vita - quella che diventerà poi rapidamente la dolce vita- che per altro è un concetto che si sono inventati gli antichi romani.

C’è inoltre la presentazione di prodotti che sono più vicini alla produzione nordamericana, quindi gli arredi, i vetri, i tessuti, ma che si differenziano perché rispondono a un gusto simile ma sono fatti molto più a mano, sono molto più accurati, e sono customizzabili.

Quindi si sceglie proprio una via che insegue una forte italianità, e questo in alcuni casi è promosso dalle comunità locali. L’esempio tipico è la famosissima mostra “Italy at Work: her Renaissance in Design Today” che gira 13 musei degli Stati Uniti tra il 1950 e il 1953: è organizzata dal Museo di Brooklyn, sede di una cospicua comunità italoamericana, finanziata attraverso un crowdfunding, e promossa attraverso rappresentazioni teatrali, tra le quali l’ultima opera di Pirandello, quindi mescolando, con una formula tipicamente nordamericana, i gala benefici a eventi di cultura alta e a fiere commerciali.

Gli italoamericani prendono questa formula nordamericana e la usano per promuovere l’Italia con un certo linguaggio che trova un punto di equilibrio tra quello che si aspetta il pubblico straniero di compratori e quello che si può dare, quindi a seconda dell’interlocutore ci sono dei piccoli aggiustamenti. Gli italoamericani sono un mezzo potentissimo di amplificazione.

Le chiedo di ricordarci il grande impatto sul Made in Italy dei tre eventi organizzati negli Stati Uniti nel 1972, nel 1981 e nel 1989

La mostra del 1972 promossa dal MOMA è ancora ad oggi la più costosa mai organizzata da questa istituzione, e la più grande in termini di investimenti finanziari, provenienti quasi tutti dall’Italia e da istituzioni e aziende molto importanti che vanno dall’Istituto del Commercio Estero ad Alitalia, dalla FIAT all’IRI, e poi tutta una serie di imprenditori dell’arredo, del cibo, della meccanica. C’è dunque un grandissimo impegno finanziario da parte di tutti gli attori della scena italiana e un grandissimo impegno curatoriale che si deve a un giovane architetto argentino che era il nuovo responsabile del dipartimento di architettura e design del Moma, Emilio Ambasz.

Questa mostra ha un enorme successo di pubblico e desta anche molte polemiche. Contiene una ricognizione su circa 250 pezzi del design italiano a partire dagli anni ‘50 con il titolo “The New Italian Landscape: Problems and Achievements of new Italian Design”: tutte le aziende sono presentate in forma di show-room, ci sono delle bacheche sulla terrazza del MOMA.

E poi invece ci sono 11 environment, come fossero delle period room, affidate a degli architetti e designer (allora la divisione non era così netta in Italia) che appartengono a varie categorie. Alcuni propongono sistemi abitativi legati a temi come la trasformabilità e il nomadismo, temi molto americani che qui in Italia in realtà si sentiva pochissimo ma che invece trovò molto favore nel pubblico americano. Poi c’è un gruppo di giovani progettisti che appartengono alla cultura radical del ’68 che influenza ovviamente tutta Italia e tutto il mondo, che invece propongono delle posizioni molto politiche, molto legate alla lotta per la casa e per l’occupazione.

Il catalogo della mostra ha anche una serie di saggi che toccano i temi dell’economia e della politica, ma il pubblico americano recepisce soprattutto questo grande fascino per gli oggetti fantasiosi, fuori via rispetto al mainstream nordamericano, e c’è una consacrazione di questo cliché della creatività della sprezzatura, un termine poco usato in Italia ma molto in voga in America, proprio con la parola in italiano. Il pubblico americano è entusiasta, e c’è una grande consacrazione del Made in Italy riconducibile anche alla sovrapposizione tra architettura e design, che era una cosa molto meno comune negli Stati Uniti.

Aspen, invece, è una serie di conferenze dedicate al design fin dal 1951 che ha l’obiettivo di mettere insieme il business e la creatività. Negli anni ‘80 si decise di dedicare conferenze “monografiche” ad alcuni Paesi: l’Italia è la sola a cui vengono dedicate due edizioni, nel 1981 e nel 1989. Nella prima edizione del 1981 c’è già un’apertura a molte discipline non strettamente legate al design così come lo intendiamo, cioè all’oggetto, perché si inizia già a parlare di cinema, musica, cucina. La differenza tra la conferenza dell’81 e quella dell’89 è la congiuntura politica ed economica mondiale. Nell’89 il quadro è quello di un mondo in cui finisce la guerra fredda e si avvia la reaganomics : il cibo è già glocal, poi c’è la moda, tutti i designer, tutti gli architetti. La conferenza ha una risonanza pazzesca, nonostante naturalmente Aspen in Colorado sia molto meno raggiungibile e frequentato del MOMA a New York.

Aspen sancisce l’evoluzione del Made in Italy non più solo legata al marchio, ma che veicola delle atmosfere, filosofie di vita, categorie molto meno palpabili, ma forse perfino più potenti per certi versi, e ha molto successo soprattutto nel mercato nordamericano, perché ci sono gli acquirenti possibili che hanno anche i mezzi per comprare cose costose, prima dell’avvento del Medio Oriente e dell’estremo Oriente. Inoltre, quello americano è il mercato più pronto ad assorbire tradizioni estere, che nel nostro caso comunque appartengono al DNA di un lungo flusso migratorio e anche di grandi fortune delle comunità italoamericane. In quest’ambito, un’altra parola che va tantissimo a descrizione dell’Italia in America è “cordiale”: ad esempio, la bellezza delle signore italiane è cordiale, meno algida di quelle francesi, è raffinata ma non distante.

L’espressione “Made in Italy” descrive l’Italia senza usare l’italiano… sempre parlando di Made in Italy, ci racconta dal punto di vista storico, culturale e imprenditoriale, lo specifico rapporto con gli Stati Uniti, oggetto del capitolo “Italy Creates: gli Stati Uniti dal Piano Marshall a Italy at Work”?

Il Piano Marshall aiuta il Made in Italy come aiuta il Made in Germany, il Made in France, il Made in Japan e in questo senso il tipo di politica è equivalente; dal punto di vista tecnico è uguale un po’ per tutti, anche perché l’obiettivo è quello di fornire degli strumenti finanziari e organizzativi soprattutto in chiave di difesa dal pericolo rosso.

Quello che è successo per il Made in Italy rispetto ad altri paesi è di nuovo la capacità degli italiani di adattare il contesto più a proprio favore, peraltro non in tutti i settori. Evidentemente questo obbiettivo nell’impresa pesante italiana non si è concretizzato in modo evidente, però lo ha fatto nel mondo del progetto, dei centri produttivi tradizionali e della media impresa, privilegiata dal Piano Marshall perché non fa concorrenza alla grande impresa americana nel campo della produzione di merci.

Ebbene in questo campo questa alchimia magica (che non si è mai più ripetuta) di alleanza tra i progettisti e gli industriali, che sono disposti a sperimentare tantissimo anche correndo dei rischi, ha la capacità di obliterare in qualche maniera la componente ideologico-politica che è chiara nei programmi nordamericani, e di restituire un qualcosa che continua a essere la dolce vita, la capacità di arrangiarsi. E’ un po’ la formula che conia un importantissimo designer americano, George Nelson, che era stato in Italia con una fellowship proprio legata agli scambi anche culturali del Piano Marshall: “Blessed are the poor”, che racconta una poetica in cui i soldi del piano Marshall vengono utilizzati con grande capacità comunicativa e senza appiattirsi a quello che si stava configurando come l’”impero irresistibile”, secondo la felice definizione della storica Victoria de Grazia.

Il Made in Italy viene rinforzato perché gli interventi del piano Marshall, soprattutto nel campo della piccola e media impresa, vengono declinati in modo da accontentare tutti, non sono fortemente politicizzati, sono de-ideologizzati: questa è la formula vincente per cui in seguito si può arrivare alla mostra del MOMA - dove arrivano contenuti politici, ma che passano decisamente in secondo piano.

Anche il successivo capitolo del suo libro ha a che fare (anche) con gli Stati Uniti: si intitola “La terza via del Made in Italy: il caso Olivetti”…

Il caso Olivetti è un tema su cui si continuano a scrivere migliaia di pagine perché è un caso studio di straordinario interesse per molti diversi aspetti. Sin da subito, già dal leggendario viaggio negli Stati Uniti di Camillo Olivetti per visitare a visitare la fabbrica di Henry Ford, l’azienda importa modelli produttivi nordamericani iniziando a fare concorrenza ai grandi produttori di macchine per scrivere e da calcolo.

Dino Olivetti, il fratello piccolo di Adriano, passa tutta la sua vita negli Stati Uniti. Nei primi anni ’50, prima con la sede, poi con lo showroom a New York e successivamente a Chicago e altre città nordamericane, vengono proposte le macchine per scrivere, con un metodo che viene lodato tantissimo dagli americani sia per gli aspetti formali sia per gli aspetti organizzativi. Ad Aspen viene detto che “IBM dovrebbe imparare dal modello aziendale Olivetti, per via del welfare, per via dell’inclusione dei progettisti, per la comunicazione”.

Quando però poi Olivetti prova a entrare nel mercato americano dell’elettronica iniziano i problemi, perché a distanza di tempo è abbastanza assodato che il fallimento in quest’ambito, nonostante l’installazione di centri di studio e di informazione Olivetti negli Stati Uniti, dipenda molto dalle ingerenze delle grandi compagnie americane dell’elettronica.

Anche in questo senso c’è uno scambio molto interessante tra i collezionisti, gli appassionati. Possedere una lettera 22 Olivetti è ancora uno status symbol, perché rappresenta quel pregio del prodotto italiano che è al tempo stesso tecnologico ma sembra una scultura: questa è la parola che ricorre più frequentemente nelle recensioni nordamericane della produzione Olivetti.

Infine le chiedo la sua opinione su una curiosa circostanza, che credo non trovi pari in nessuna altra parte del mondo. Dando per scontata la differenza culturale e antropologica dei due popoli, cosa pensa del fatto che in America l’espressione “Italian style” abbia un significato molto spesso positivo, che si riferisce al lusso, alla cura dei dettagli e al talento, mentre noi in Italia usiamo il corrispettivo “all’Italiana” quasi sempre con un valore negativo e contrario a quello usato in America?

Provo a dare una risposta da storica, pur con il rischio di generalizzare. Nei moltissimi articoli dedicati all’Italia soprattutto nell’immediato secondo dopoguerra da parte della stampa americana, una cosa che viene sempre evocata - oltre al già menzionato “Blessed are the Poor” - è che gli italiani hanno questa capacità di arrangiarsi, e di raggiungere dei risultati eccellenti con poco dal punto di vista delle risorse ma con un po’ di furbizia e con l’adattabilità, con la creatività che viene raccontata come una dote, una qualità.

Il confine tra qualità e negatività è sottilissimo, per cui vista da lontano gli americani dicono “guarda come sono riusciti ad arrangiarsi e ad ottenere ottimi risultati”, a volte non sapendo esattamente cosa c’è dietro. Noi che siamo più dentro e quindi conosciamo di più i meccanismi e come quelle furbizie spesso significhino aggirare le norme, se non infrangerle apertamente, ne diamo una descrizione diversa, magari esagerandone gli aspetti negativi.

Per cui mi sembra abbastanza evidente che la capacità di rinascere (c’è un articolo di uno scrittore americano che dice che gli italiani sono come una fenice, sempre capaci di rinascere dalle proprie ceneri), vista da lontano ha un sapore, un po’ eroico, visto dall’interno può averne tutto un altro.