The stories of the successful Italians in Silicon Valley have a meaning that goes far beyond the simple yet wonderful description of our compatriots who see their talent recognized in the most innovative and competitive environment in the world. These stories convey that innovation and competition are perfectly combined with Italianism, and for this reason they should be pursued and supported much more than what is done in Italy.

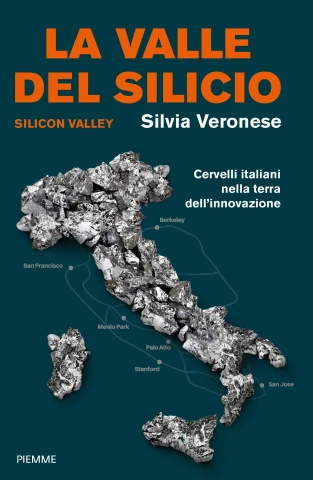

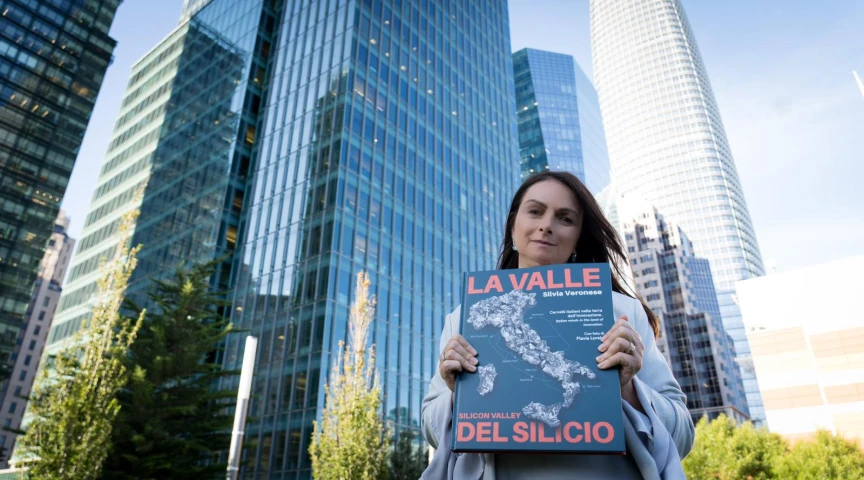

That's why we are grateful to Silvia Veronese for writing the beautiful book "La valle del silicio" and for being the protagonist of this interview on We the Italians, which we are particularly pleased about.

Silvia, first of all, tell us something about you. Where were you born, what brought you to Silicon Valley, and what do you do now?

My family is from Verona, and that's where I was born not too many years ago, but I've been around a lot. Ten years in Brescia, then near Piacenza and Aosta Valley, study in Pavia, first job in Milan. Then came, almost by chance, a job offer from IBM Milan and one from IBM New York. In New York the position was the so-called 'post-doc', which would have allowed me to work in the field of scientific research.

So I said to myself, "Why not?" and I ended up working in the field of quantum chemistry (which is absolutely not my specialization, since I am a mathematician) and more precisely in the team that built the first parallel computer, capable at that time of executing operations of several orders of magnitude faster than the computers of that time. It was the dawn of artificial intelligence. That was the same computer that beat Garik Kasparov, chess world champion and considered by many the greatest player of all time.

Between NY and Silicon Valley there was a stop in the middle of about 10 years at the University of Utah, where I taught and did research in the Mathematics Department. These were very interesting years because these were the dawn of Big Data (which at the time was not that), where the development of new computer architectures made it possible to create increasingly precise mathematical models in all fields, from medicine to biology to economics.

I didn't move to Silicon Valley because of its fame and its name. That was another one of those serendipitous "why not?" moments, in 2000. If you move from Utah to California you can do it by driving, and even there it was an invitation, from someone who later became a dear colleague and friend. We created our first startup; it was the time of the Internet. We would measure the performance of the Internet, the speed at which the various sites were reachable by users. An office in Menlo Park as big as a closet, IKEA furniture that we assembled ourselves, and access to Yahoo's data center, which then became our first customer. We were a physics and mathematics group at Stanford, working on everything, there were no defined roles, writing software, working with clients, and at the same time courting VCs, the Venture Capitalists, to get the next round of funds. Since that time the things I ventured in other jobs: another startup (in the field of high frequency trading), consulting, and board member of various startups. Today I'm Senior Vice President for Thales, a large multinational company that develops artificial intelligence and machine learning systems in aerospace, telecommunications (Thales produces SIM cards in mobile phones), security and defense.

How did you come up with the idea to write the book?

It was a couple of years ago. I'd say it was almost a challenge to myself. I was never cut out for writing, and honestly, I've had a bitter memory of it since school. In those days there was no literary vein, it was hard to write and fill the two fateful exam sheets with thoughts that were not trivial. What we didn't understand at the time (or at least I didn't understand) is that the act of writing is not only for us, but by writing we become messengers. Writing is not an end in itself; it is a way to send a message of change and reflection to those who read it. Over the years, and being far from Italy, you want to tell stories, to capture what is escaping in this society. To capture the "humans of the Silicon Valley", or rather the Italians of Silicon Valley.

The occasion for the book then came when the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation announced an initiative for special projects through the Comites. I wrote the proposal in less than half an hour, one evening after work. Absolutely in a hurry, with lots of ideas and maybe even lots of dreams. Sent to the Consulate in San Francisco, the proposal was accepted almost immediately. And then, with that unawareness of how I get into something bigger than myself, I really had to do the book.

The book tells the stories of some of the great Italians in Silicon Valley: entrepreneurs, academics, visionary innovators... please, tell us some of these stories.

There is the story of Janet Napolitano, a woman who is not easy to forget, the first woman to hold the position of Secretary of National Security of the United States. She tells, in the words of her grandfather who landed at Ellis Island, how she regrets not speaking Italian well: because, as she told me, "in my days we had to integrate as soon as possible so as not to be marginalized".

And then there is the story of Federico Faggin, who is the best living representation of those who believe in themselves and their intuitions. Federico, pioneer and creator of the first microprocessors, tells with incredible simplicity how he is studying knowledge. Bill Gates once said about him: "Before Faggin, Silicon Valley was simply the Valley."

I discovered from Luca Maestri, Apple's CFO, who gets up at 4:30 in the morning, that working at Apple is like belonging to an army and, at the same time, to a monastery. Because iron discipline is necessary in everything you do. But Luca doesn't lose his Italianness. Among the billions he manages for Apple, he also finds time to join the Juventus club in Silicon Valley with his friends.

I was so fascinated by the story of Michele Battelli who was able to marry his work at Google with the mountains. He climbed Everest in the infamous year of the earthquake that killed more than 9000 people in Nepal. Although we didn't know each other at the time, we almost met in Kathmandu; my daughter and I had arrived there to work with the communities in the Everest valley that had been most affected. He was returning from his expedition where he had lost his partner in an avalanche.

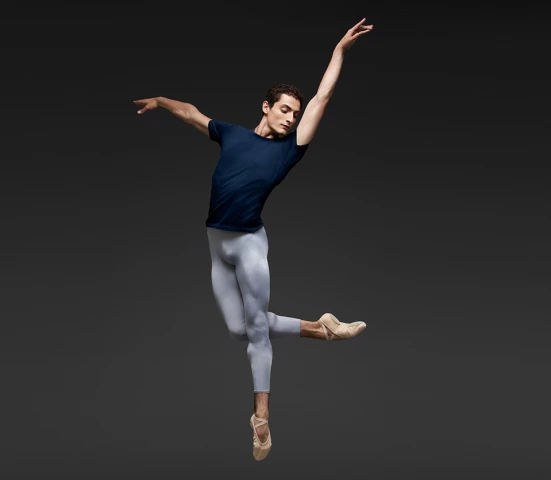

And among scientists and innovators, there are also artists. There is the story of Carlo Di Lanno, the Billy Elliot of America, who started out from a small town near Naples, with enormous sacrifices by his family, and is now the Principal Dancer of San Francisco Ballet.

What is the typically Italian common element that has allowed these compatriots of ours to succeed in such a competitive environment as Silicon Valley?

The Italian brings with him the Renaissance genetics of being able to act under the most diverse circumstances. To be successful you need to transform and adapt. Silicon Valley is a relatively small place. It's just a little bit bigger than Rome. Now think of a place where 60-70% of people work in the same field, either high-tech or bio-tech. Relationships are very close, there are no "6 degrees of separation" here, there are 2, 3 at most. Italian people excel in social relations and we excel in science, thanks to our schools and our tradition in science. In the end, it is a combination of many qualities that helps us.

One of the concepts your book insists on is failure: "Failure is a symbol of progress, not a stigma." We know that in Italy, unfortunately, it is the opposite, and it is a big mistake. How can we reverse the approach here too?

Unfortunately, the stigma of failure is something that permeates Italy. From an early age we are obsessed with the threat of "not making a good impression". In my opinion, in Italy we can't let go of the image and really be ourselves. It almost seems that each of us builds a Facebook-like image, always cheerful, always happy and always on holiday. What Italians in Italy don't understand is that you learn more by observing others, not trying to be ahead of everyone. We need to change the way people, young people in particular, are rewarded. And above all, create more dynamism in the system. Let's give up the permanent position. But let's be clear: failure is not a pleasant thing. It's not the goal. It's not what we have to aspire to. Failure is not part of the educational process, as it is to make mistakes. When a child learns to walk, takes one step at a time, falls and cries, that's not failure. If the child does not get up and does not want to learn to walk, that is failure. Making mistakes during a growth process is part of how we learn. And what we call here "trial and error."

What would you transplant from Italy to America?

Food. The art, the beauty of our cities. The respect for history and traditions. Our school.

And what if you had to take something American and put it into the macrocosm formed by the Italian environment, economy, society, business and culture?

The pioneer spirit, positive attitude, social mobility, respect for diversity.

What is the future of Silicon Valley, in general and in particular with reference to the Italians who live and work there?

First of all you have to define what Silicon Valley is: is it a place, a name for a certain type of industry or a group of people united by time, geography and a common mission? I hope that this area will continue to thrive on ideas, but above all I hope that Silicon Valley will become an example to be replicated in Europe and in Italy. I hope that a similar model will be copied and adapted. We must try to create points of interest, think tanks that allow those who want to brainstorm to try and try again.

In the book you write that the Italians of Silicon Valley "did not close a door behind them, they did not run away from anything, but opened a door in the future, they followed an opportunity. Immensely grateful and proud to be Italian, they have never forgotten Italy and count on coming back". What must Italy do to facilitate their return, your return?

I want to dispel a myth, a myth that perhaps was created at the beginning of the century when the Italian left by ship for America and never came back. The new generation of the 21st century is made of people who come and go from Italy. They live here for a few months, but they are connected to their alma mater, to their city. They participate in entrepreneurial activities, organize, help in schools, and serve as inspiration to young students. Look at the example of Fabrizio Capobianco who directed his company from here, but with engineers in Pavia, or like Andrea Carcano from Nozumi Networks who did something similar. There are also examples like Massimo Sgrelli and Luigi Baietti, Italian venture capitalists that look for investors here, to propose Italian startups to them. In Italy, the contribution of the Italians of Silicon Valley is starting to be felt, because we are all looking for the opportunity and it doesn't have to be abroad. Not everyone is coming back, but what matters is to continue to open the channels of collaboration.

Le storie degli italiani che hanno successo in Silicon Valley hanno un significato che va ben oltre la semplice ancorché meravigliosa descrizione di nostri connazionali di talento che lo vedono riconosciuto nell’ambiente più innovativo e competitivo del mondo. Queste storie raccontano che innovazione e competizione si sposano perfettamente con l’italianità, e per questo andrebbero perseguite e sostenute molto di più quanto non si faccia in Italia.

E’ per questo che siamo grati a Silvia Veronese per aver scritto il bel libro “La valle del silicio” e per essere la protagonista di questa intervista su We the Italians, della quale siamo particolarmente lieti.

Silvia, per prima cosa dicci qualcosa su di te. Dove sei nata, cosa ti ha portato in Silicon Valley, e cosa fai ora?

La mia famiglia è di Verona, ed è li che sono nata non troppi anni fa, ma ho girato parecchio. Dieci anni a Brescia, poi vicino a Piacenza e in Valle d’Aosta, studi a Pavia, primo lavoro a Milano. Poi arriva, quasi per caso, un’offerta di lavoro da IBM Milano e una da IBM New York. A New York la posizione era il cosiddetto “post-doc”, cioè quello che in italiano di chiama “Assegnista di ricerca” che mi avrebbe permesso di lavorare nel campo della ricerca scientifica.

E quindi mi sono detta “Perché no?” Sono finita lavorare nel campo della chimica quantistica (che non è assolutamente la mia specializzazione, dato che io sono una matematica) e più precisamente nel team che costruì il primo calcolatore parallelo, capace a quel tempo di eseguire operazioni di diversi ordini di magnitudine più velocemente dei calcolatori d’epoca. Erano l’alba dell’intelligenza artificiale. Quello era lo stesso computer che battè Garik Kasparov, campione del mondo di scacchi e considerato da molto il più grande giocatore di tutti i tempi.

Tra NY e la Silicon Valley, ci fu una tappa in mezzo di circa 10 anni, all’Università dello Utah dove ho insegnato e fatto ricerca nel Dipartimento di Matematica. Furono anni interessantissimi perché questi erano gli albori del Big Data (che al tempo non si chiamava così), dove lo sviluppo delle nuove architetture di computer permettevano di creare modelli matematici sempre più precisi in tutti i campi, dalla medicina, alla biologia all’economia.

Non mi sono spostata in Silicon Valley per la sua fama e per il suo nome. È stato un altro di quei momenti di serendipity, o del “perché no?”, nel 2000. Dallo Utah alla California ci si arriva in macchina, ed anche lì è stato un invito, da una persona che poi è diventata un carissimo collega ed amico. Abbiamo creato la prima startup, erano i tempi di Internet. Misuravamo le prestazioni di Internet, la velocità in cui i vari siti erano raggiungibili dagli utenti. Ufficio a Menlo Park grande come uno sgabuzzino, mobili IKEA che ci siamo montati da soli ed accesso al data center di Yahoo, che poi diventò il nostro primo cliente. Eravamo un gruppo fisici e matematici di Stanford, si lavorava su tutto, non c’erano ruoli ben definiti, scrivevamo software, lavoravamo con i clienti, e allo stesso tempo facevamo la corte ai VC, i Venture Capitalists per ottenere il prossimo round di fondi. Da quei tempi di cose ne ho fatte, un’altra startup (nel campo dell’high frequency trading), consulenza, e board member di varie startups. Oggi sono Senior Vice President per Thales, una grande multinazionale che sviluppa sistemi di intelligenza artificiale e machine learning nel campo aereospaziale, delle telecomunicazioni (Thales produce le SIM Cards che abbiano nei telefonini), della sicurezza e della difesa.

Come ti è venuta l’idea di scrivere il libro?

È successo un paio di anni fa. Direi quasi una sfida a me stessa. Non sono mai stata portata alla scrittura e sinceramente ne avevo un ricordo amaro dai tempi della scuola. A quei tempi la vena letteraria non c’era, si faceva fatica a scrivere e riempire i 2 fatidici fogli dei compiti in classe con pensieri che non fossero banali. Quello che al tempo non si capiva (o che almeno io non avevo capito) è che l’atto della scrittura non è solo per noi, ma scrivendo si diventa messaggeri. La scrittura non è fine a se stessa è un modo per mandare un messaggio di cambio e riflessione a chi ti legge. Con gli anni, e la mancanza dell’Italia, ti viene voglia di raccontare storie, di catturare quello che in questa società sfugge. Di catturare the “humans of the Silicon Valley”, o meglio gli Italiani della Silicon Valley.

L’occasione del libro poi è arrivata quando il Ministero degli Esteri e della Cooperazione Internazionale annunciò un’iniziativa di progetti speciali tramite il Comites. Scrissi la proposta in meno di mezz’ora, una sera dopo il lavoro. Assolutamente di getto, con tante idee e forse anche tanti sogni. Mandata al Consolato di San Francisco, la proposta fu accettata praticamente subito. E poi, con quella incoscienza di saper essermi cacciata in una cosa più grande di me, il libro lo ho dovuto veramente fare.

Il libro racconta le storie di alcuni grandi italiani in Silicon Valley: imprenditori, accademici, innovatori visionari… ti chiediamo di raccontarci qualcuna di queste storie

C’è la storia di Janet Napolitano, donna che non si dimentica facilmente, prima donna a ricoprire la carica di segretario della Sicurezza nazionale degli Stati Uniti. Lei racconta, con le parole di suo nonno sbarcato ad Ellis Island, di come rimpiange di non parlare bene l’italiano: perché, come mi ha detto, “ai miei tempi ci si doveva integrare al più presto possibile per non essere emarginati.”

E poi c’è la storia di Federico Faggin, che è la miglior rappresentazione vivente di chi crede in se stesso e nelle sue intuizioni. Federico, pioniere e creatore dei primi microprocessori, racconta con una semplicità incredibile di come sta studiando la consapevolezza. Di lui Bill Gates ha detto: “Prima di Faggin, la Silicon Valley era semplicemente la Valley.”

Ho scoperto da Luca Maestri, CFO di Apple, che si alza alla 4:30 del mattino, che lavorare ad Apple è come appartenere ad un esercito e, al tempo stesso, a un monastero. Perché la disciplina ferrea è necessaria in qualsiasi cosa tu faccia. Ma Luca non perde la sua italianità. Tra i miliardi che gestisce per Apple, trova anche il tempo per partecipare al club della Juventus della Silicon Valley con i suoi amici.

Mi ha affascinato tantissimo la storia di Michele Battelli che ha saputo sposare il lavoro a Google con la montagna. Ha scalato l’Everest nell’anno infame del terremoto che ha ucciso più di 9000 persone in Nepal. Anche se a quel tempo non ci conoscevamo, a Katmandu ci siamo quasi incrociati, mia figlia ed io eravamo arrivate lì per lavorare con le comunità della valle dell’Everest che erano rimaste più colpite. Lui era di ritorno dalla sua spedizione dove aveva perso il suo compagno in una valanga.

E tra gli scienziati ed innovatori, ci sono anche gli artisti. C’è la storia di Carlo Di Lanno, il Billy Elliot dell’America, partito da un paesino vicino a Napoli, con enormi sacrifici della sua famiglia ora è primo ballerino di San Francisco Ballet.

Qual è l’elemento comune tipicamente italiano che ha permesso a questi nostri connazionali di avere successo in un ambiente così competitivo come quello della Silicon Valley?

L’italiano porta con sé la genetica rinascimentale di sapersi muovere sotto le più diverse circostanze. Per avere successo bisogna trasformarsi ed adattarsi. La Silicon Valley è un luogo relativamente piccolo. È appena un po’ più grande di Roma. Ora pensa ad un luogo dove il 60-70% delle persone lavora nello stesso campo, o è high-tech o bio-tech. I rapporti sono molto stretti, qui non esistono i “6 degrees of separation”, ce ne sono 2, 3 al massimo. L’italiano eccelle nei rapporti sociali, gli italiani eccellono nelle scienze, grazie alle nostre scuole e alla nostra tradizione nella scienza. Alla fine è un connubio di tante qualità che ci aiuta.

Uno dei concetti sul quale il tuo libro insiste è quello di fallimento: “Il fallimento è un simbolo di progresso, non una stigma.” Sappiamo che in Italia purtroppo è invece il contrario, ed è un grande errore. Come si fa a rovesciare l’approccio anche da noi?

Purtroppo lo stigma del fallimento è una cosa che permea l’Italia. Fin da piccoli veniamo ossessionati dalla minaccia di “non fare bella figura”. Secondo me, in Italia non riusciamo a lasciar perdere l’immagine ed essere veramente noi stessi. Sembra quasi che ognuno di noi si costruisca un’immagine tipo Facebook, sempre allegra, sempre felice e sempre in vacanza. Quello che gli italiani in Italia non capiscono è che si impara di più osservando gli altri, non cercando di essere davanti a tutti. Dobbiamo cambiare il modo in cui le persone, i giovani in particolare, vengono premiati. E soprattutto creare più dinamismo nel sistema. Abbandoniamo il posto fisso. Ma siamo chiari: fallire non è una bella cosa. Non è il goal. Non è quello a cui dobbiamo aspirare. Il fallimento non è parte del processo educativo, come invece lo è fare degli errori. Quando un bambino impara a camminare, fa un passo dopo l’altro, cade e piange, questo non è fallimento. Se il bambino non si alza e non vuole imparare a camminare, questo è fallimento. Fare errori durante un processo di crescita, è parte della maniera in cui impariamo. E quello che qui chiamiamo “trial and error.”

Cosa trapianteresti dall’Italia in America?

Il cibo. L’arte, la bellezza delle nostre città. Il rispetto per la storia e per le tradizioni. La nostra scuola.

E se dovessi invece prendere qualcosa di americano e inserirlo nel macrocosmo formato da ambiente, economia, società, imprenditoria e cultura italiane?

Lo spirito pioniere, l’attitudine positiva, la mobilità sociale, il rispetto per la diversità.

Qual è il futuro della Silicon Valley, in generale e in particolare in riferimento agli italiani che la compongono?

Prima di tutto bisogna definite cosa è la Silicon Valley: è un luogo, un appellativo per un certo tipo di industria o un gruppo di persone accomunati dal tempo, dalla geografia e da una missione in comune? Mi auguro che questa zona continui a prosperare di idee, ma mi auguro soprattutto che la Silicon Valley diventi un esempio da replicare in Europa e in Italia. Che un modello simile venga copiato ed adattato. Bisogna cercare di creare poli di interesse, dei think tanks che permettono a chi vuole di fare del brainstorming a provare e riprovare.

Nel libro scrivi che gli italiani della Silicon Valley “non hanno chiuso una porta dietro di loro, non sono scappati da nulla, ma hanno aperto una porta nel futuro, hanno seguito un’opportunità. Immensamente grati e fieri di essere italiani, non hanno mai dimenticato l’Italia e contano di tornare.” Cosa deve fare l’Italia per agevolare il loro, il vostro ritorno?

Voglio sfatare un mito, un mito che forse si è creato all’inizio del secolo quando l’italiano partiva in nave per l’America e non tornava più. La nuova generazione del XXI secolo è fatta di gente che va e viene dall’Italia. Vivono qui per qualche mese, ma sono collegati alle loro alma mater, alla loro città. Partecipano ad attività imprenditoriali, organizzano, aiutano nelle scuole, e servono da ispirazione ai giovani studenti. Vedi l’esempio di Fabrizio Capobianco che ha diretto la sua società da qui, ma con ingegneri a Pavia, o come Andrea Carcano di Nozomi networks che ha fatto una cosa simile. Ci sono poi anche esempi come Massimo Sgrelli e Luigi Baietti, Venture Capitalists italiani che gli investitori li cercano qui per proporli a startup italiane. Il contributo degli Italiani della Silicon Valley in Italia sta cominciando a farsi sentire, perché appunto tutti noi cerchiamo l’opportunità e non deve necessariamente essere all’estero. Non tutti tornano, ma quello che conta è continuare ad aprire i canali di collaborazione.