At a time when we still have to painfully realize how much the racial question is an open wound in the evolution of the United States of America and a very urgent situation to be resolved, our Italian heart in love with America is also shaken by the specious and mistaken attempts to promote hostility between the African American and Italian communities.

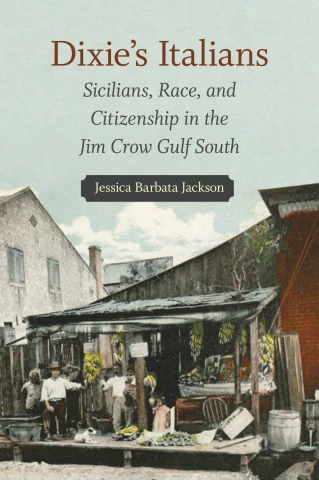

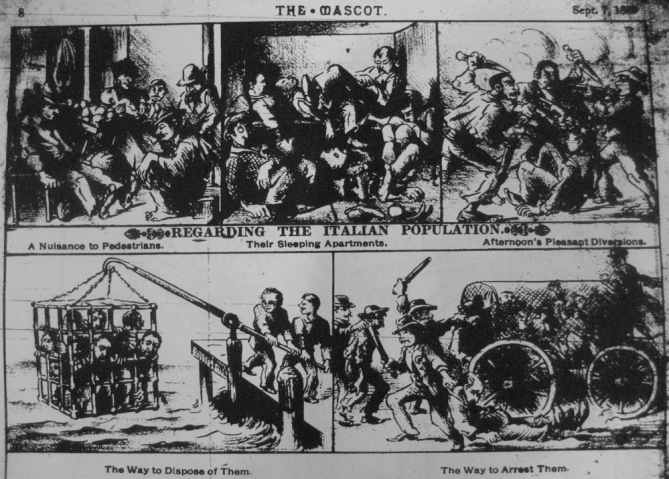

The history of Italians in the South of the United States tells us that if there is an ethnic group that is not black that has received humiliation, discrimination, stereotypes and violence that is not at all comparable in numbers to the horrors that have been perpetrated against African Americans, but no less serious for that, that ethnic group is the Italian one. These are interesting and painful stories that no one has the right to forget or deny or, even worse, manipulate for current ideological reasons. This is why we thank Professor Jessica Barbata Jackson, author of a fundamental volume to understand these issues: Dixie's Italians: Sicilians, Race, and Citizenship in the Jim Crow Gulf South

Professor, first of all please tell us about your Italian heritage. In which Italian region are your origins?

My great-grandparents were Italian, from a small village, Ginestra degli Schiavoni in the province of Benevento in Campania. My grandfather was born in the United States. My great grandfather, Terigio, immigrated around 1910, first to Ellis Island, and then to the Bay Area near San Francisco. They were actually Barbato, originally, but there was an error at Ellis Island, and they became Barbata on paper. Italy is the only place where I never had to spell my maiden name.

My father grew up in the 1950s, and there was a push to Americanize: he was not raised very much Italian, and so it wasn't necessarily something that was passed down more directly to me. I actually studied abroad in Florence when I was at the University and then taught English for a few summers in Italy to Italian schoolchildren. So I've tried to reclaim access, I guess, to my Italian heritage through my own traveling and working experience and then with my research.

Please tell us how and why you decided to write Dixie's Italians: Sicilians, Race, and Citizenship in the Jim Crow Gulf South

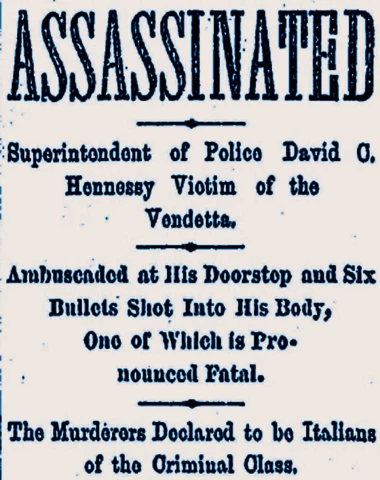

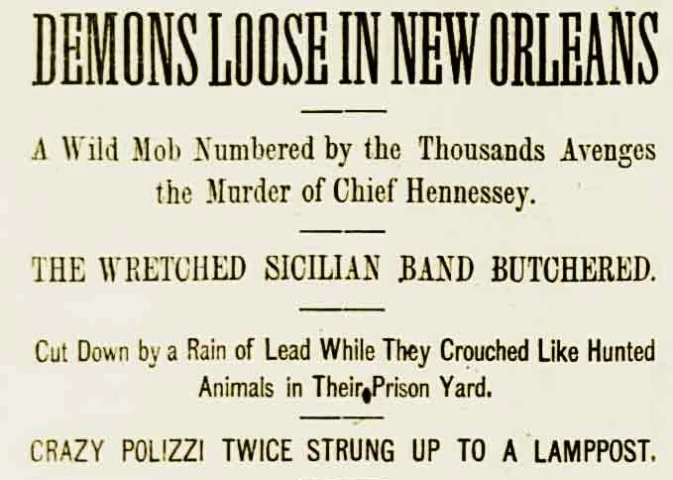

Before I started graduate school, to become a history professor, I was actually a high school history teacher. I was always really fascinated with immigration history, in general. When I first started graduate school, I was not very familiar with the history of how Italians became white. And as I started doing research, there was a great deal of literature already on that subject, but something was missing. There was history of immigration in the third wave in the US in the 1880s to the 1920s, focused on Boston and New York and Chicago. We generally think of this immigrant experience just to these urban ports. But I was reading, for another course, some books on early New Orleans in Louisiana, and I became really fascinated with how race was operating, the sort of layered multi-racial experience in Louisiana. I stumbled across the story of the 1891 lynching of 11 Italians in New Orleans, which was one of the largest mass lynching in US history. And so that was sort of the opening story for my dissertation work. I started to realize that there were three different kind of stories I was looking at: immigration history, Southern/Louisiana racial history, and modern Italian history—and layering them on top of each other, it became just really fascinating.

First it was a recovery of stories that we hadn't heard before, some of these lynching experiences, the voting experiences of Italians in the south: there is a complicated racial experience already going on in Louisiana, because of the French and Spanish presence.

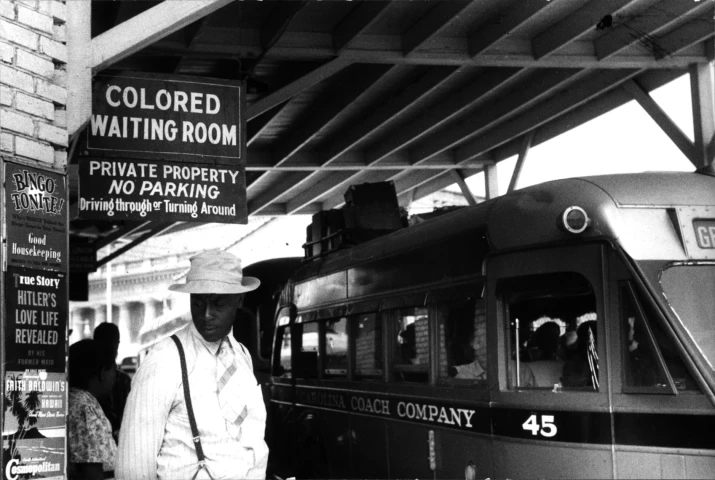

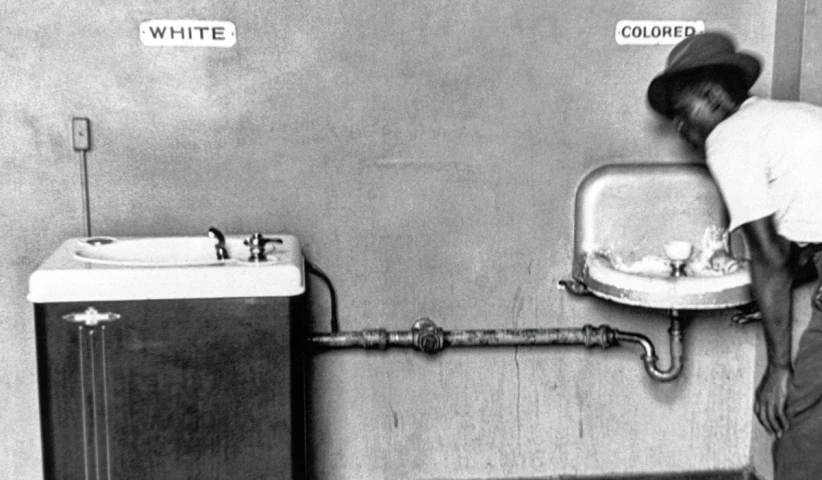

Then we had Jim Crow laws being imposed in this time period, the segregation laws, the effort to make the South this black-white binary, when you have Italians who are kind of in between, a sort of “gray” racial experience. So what happens when the Italians arrive into what is supposed to be a binary racial structure?

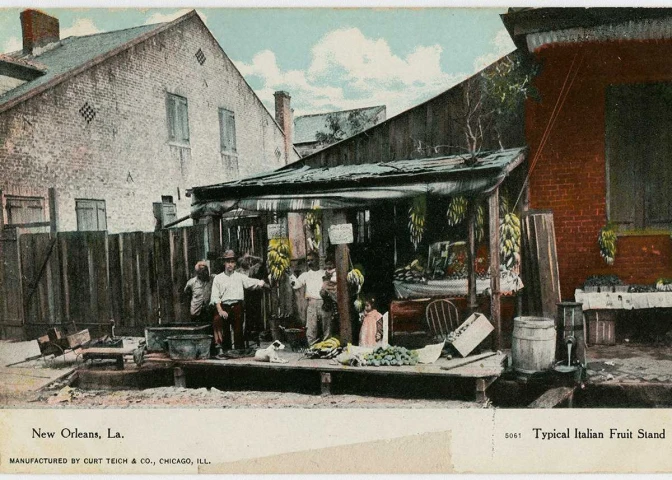

And then I became really fascinated by bringing the narrative of Italian Risorgimento and unification and the fact that 90% of the immigrants I was looking at, in New Orleans, were actually Sicilian. That brought this whole other complicated story about looking at this North versus South Italians, the regional identities that these immigrants were bringing, that they were Sicilian, they didn't speak Italian, and yet they were called Italians. So it was really about just mixing together these three different immigration histories into my dissertation, which then became this book.

Are there differences between the stories of Italian and Sicilian emigration in Louisiana and those in other parts of the South?

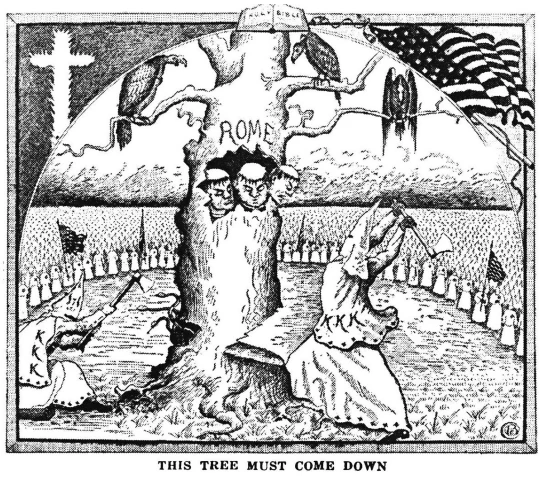

Yes, there is a difference. I would put Mississippi and Alabama in one category, because even if there aren't lynching and Alabama, I do have some stories taking place in Alabama. The difference is that the largest Italian population is in Louisiana and starts spreading out first in New Orleans and then to plantation industries throughout Louisiana. But the biggest difference is that New Orleans is a very cosmopolitan Creole city. And I say Creole in the sense that there is a multiplicity of races coming together with French and Spanish heritage. When we look at how Italians are being perceived in New York, anti-Catholicism is actually a big part of what is driving some of the anti-Italian sentiment. But that is not at all the case in a place like New Orleans where there was a greater acceptance for Catholicism, greater acceptance for these different groups coming together. And I would say that is not the case in Mississippi and Alabama.

So the anti-Italian sentiment in the story I followed in Mississippi with these Italian schoolchildren, actually is about anti-Catholicism: an effort to move out the Catholic Italians, together with the Ku Klux Klan movement in Mississippi, where one of their driving forces is their anti-Catholicism. The differences are partly due to demographics, because Italians are working in different industries, but is also due to their ability to integrate: this is why the anti-Italian sentiment is going to be driven by very different factors in Louisiana with respect to those in Mississippi. In Mississippi the Italians were working in the timber industry, while they were working in the mining industry in Birmingham, Alabama. But if we look at the relationships between Italians and people of color in New Orleans, it’s a very different scenario from the one in Alabama and Mississippi.

Let's talk about lynchings. It's bad enough that not everyone knows the story of the 1891 one in New Orleans, but there have been others that are virtually unknown to those who haven't read your book....

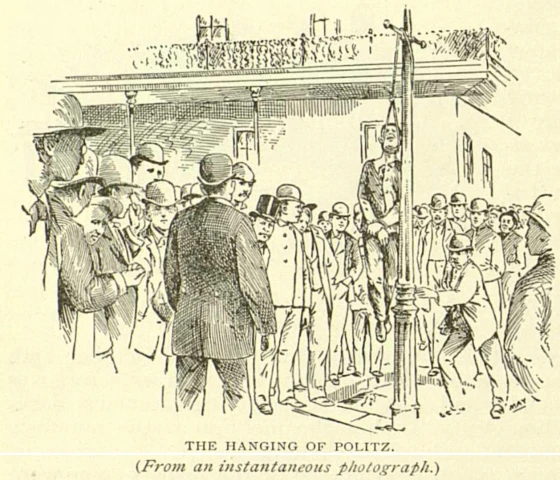

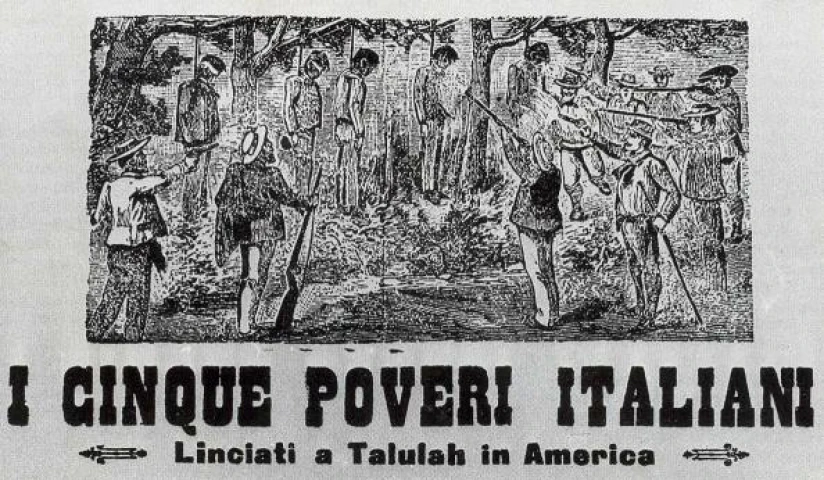

True. About two dozen Italians were lynched in the South in this time period, even if, of course, by no means this even comes anywhere close to the lynching of Black Americans. Nine out of ten lynchings are of Black Americans, but to me, it's very striking that Italians are the only Europeans who have been lynched in large numbers. So even when we look outside of the South, and we look at other sites of lynching, the West, Texas, even Colorado, the lynching victims are Black Americans, Native Americans, indigenous persons, Mexican, Chinese, and Italians.

Why did this happen? Why is this particular group being rendered non-white enough they could be privy to a very racial violence, a very vigilante racialized violence, like lynching? I specifically looked at the lynchings in Mississippi and Louisiana, and then I tried to uncover the time and place context. Or rather, by trying to understand why Italians are being lynched, I discovered that there were very contextual factors going into each of these lynching.

Part of the argument I tried to make is that it's not that Italians are being lynched specifically because they are Italian; but because they are Italian, they could be lynched. And then it's the time and place context that leads to these particular forms of violence. So you have 1896, in Hahnville, Louisiana, you have three Italians, Sicilians actually, who are lynched. Two of them, just because they happen to have been in jail at the time that a prominent Louisianian had been killed. And even if the person accused of killing him was in jail, they end up lynching all three of these Sicilians.

Then Louisiana in 1899, there's five Sicilians who are lynched. And the story here is really complicated. Three of them are brothers. They are accused of killing a doctor in the town, even if in the end the doctor survives. Maybe there's some deep-seated fears of economic competition. So it's almost as though the lynchings are not because these men are Italians, or Sicilians, but because they find themselves in situations where they could be guilty of something because of their economic situation, but not because they are Italians.

I’ve always been very fascinated by the story of miscegenation (the crime of racial mixing) and in particular the Jim Rollins story, also because it happens incredibly in 1922, the same year when in Italy the promotion of our country as a strong white nation is very popular…

The actual story is a bit more complicated of how the story is generally told. So, Jim Rollins is an African American man, he and Edith Labue, a white woman, have a consensual relationship. Her husband goes off to fight in World War One. He comes back and she's pregnant: it could be her husband's child, depending on the time line, but maybe it's not.

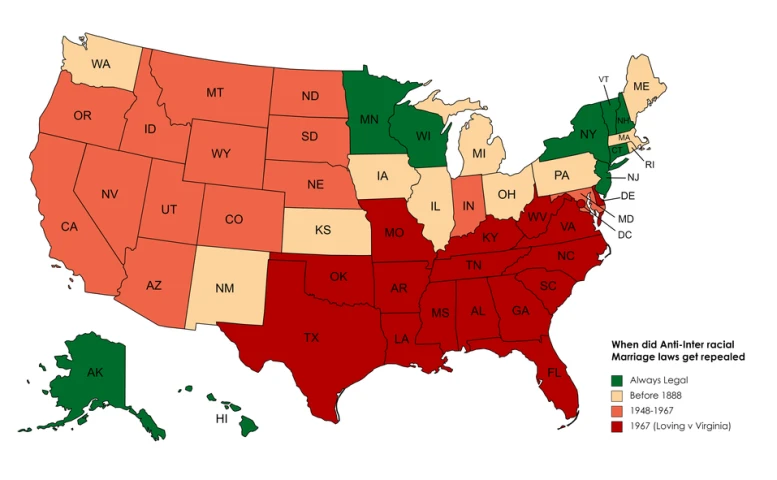

The whole miscegenation issue is a law that says that you cannot marry someone from a race different than yours, but it’s not that police are going around trying to find these relationships: they are going to be investigating just things that are reported. So somebody would have had to report this situation. What marriage laws are trying to do in this time is to regulate visible relationships, rather than necessarily interracial sex or interracial intimacy. There's a lot of interracial relationships throughout the entire 19th century, between slave masters and enslaved persons, and the law is very much trying to render invisible these public relationships.

Anyway, the police arrives and burst into the Labue home, and they find Jim Rollins and Edith Labue in a back room, not a bedroom, but apparently it was dark: they had all the clothes on, and they arrest them. Both of them are arrested. So Edith Labue is arrested as well for violating the miscegenation laws. At this point, by the time the arrest takes place, I believe the child has already been born, because the child is used in the trial. There’s some evidence that the police coerced a confession out of Jim Rollins, they were brandishing a weapon, and forced him to confess that he had a relationship with Edith Labue.

They’re both convicted. And so Edith Labue goes to jail, too. It’s unclear to me exactly what happens to her, and I'm wasn’t able to find a whole lot of records about her, but she's released a few months later. This is 1921. In 1922, Jim Rollins goes up for an appeal case, and this is where it gets a little tricky. Most scholars and historians just read the summary of the appeal ruling: yes, his conviction was overturned, because, the summary reads, that Edith Labue was not considered a “white woman”, and therefore he hadn't violated the miscegenation statute. But I have tracked down, with the help of another historian that actually used the court transcripts, and I think the transcripts tell a slightly different story.

In the court transcripts, when they're evaluating whether or not Jim Rollins violated the statute, their only evidence is Edith Labue’s third child, and they actually bring the child into the courtroom three different times and they talk about how the child has kinky hair and how the child has darker skin. We don't have photographic evidence about the child, what we know is what they're saying: the court transcripts don't say yes or no. They talk about the child being different than the two older Labue's children.

Edith Labue’s husband is actually a witness for the prosecution, so he's actually testifying against his wife, and he also says that he is actually not Sicilian, that he's never been to Africa. He's really trying to distance himself from being Southern Italian and actually arguing that his wife is maybe from somewhere near middle Italy. He's trying to argue that she is white, specifically trying to separate himself and his wife from being Southern Italian. So there's definitely this argument going on between being Northern Italian and Southern Italian. From about 1908 for at least a decade, US Census reports are identifying North Italy and South Italy as different countries and even different races. So Edith’s husband is very much trying to make this case that she is middle Italian, she's not this sort of suspected Southern Italian, Sicilian, and so that she did, in fact, violate the miscegenation statute.

It's unclear what's going on behind closed doors, obviously, but the judge ends up ruling that the prosecution did not prove their case, because the law just says that a single act of interracial sex does not violate the statute, and that there has to be evidence of an ongoing relationship. That, to me, is what ends up overturning the ruling: that the only evidence they had was this child and therefore they only had evidence that maybe there was an interracial relationship one time, but that they didn't necessarily have evidence, or they weren't able to prove, that there was an ongoing relationship. But this doesn’t make the story less striking.

I don't read it as Edith Labue being suspectedly non-white, because they don't evaluate her race in the same way they do in other interracial or miscegenation cases. When courts are evaluating a person’s race, they would determine it based on personal interactions and behaviors, so they would say: "Well, so she went to the black church, and she had these people over to her house. So she must be non-white." They're not analyzing and evaluating her race in the same way that I see in other miscegenation cases. So I don't necessarily think it's evidence that her whiteness was sort of denied. But there definitely is a Sicilian / Southern Italian / Middle-Northern Italian narrative that's playing out here. And this is very much evidence of the complicated fact that there is this suspect conversation even going on about this sort of “in betweenness,” the racial “gray” area of Southern Italians. I find it absolutely fascinating.

Are there any anecdotes similar to Jim Rollins' that can be told to our readers to further explain the situation of Italians in the South of the United States?

The fifth chapter of my book is about these miscegenation cases, to what extent Italians are intermarrying with persons of color, and I did find instances where, even in Louisiana, even when a relationship would have been illegal according to the State's marriage laws, I've found evidence of an Italian man and a woman of color who had a marriage license. This means that the State validated this relationship, gave them official sanction, so they're reading this Italian person as non-white enough to be able to have a marriage license with this woman of color. It's not just that they're living together, they received official sanction to have a legal marriage, even if whites and non-whites were not allowed to marry.

Could this be a misogynist thing? I mean, could be that back in those days a white man was allowed to have relation with a black woman, because in addition to the different treatment of people based on the color of their skin, there is also that women were not treated equally?

Yes, it could be something like that. All of this is happening at a very local level. So, yes, there are laws, but it's the marriage licensing operator who is reading the bodies, making the decisions. Certainly white men would have had more "prerogative" to do what they wanted, but it's rare in this time period when Jim Crow laws and these marriage laws are being imposed, that white men, regardless of being Italian or non-Italian, would have been granted legal sanction if it was in violation of the State's marriage laws.

Another phenomenon I discovered is the one of Italian families changing race. There's one I stumbled across that I talk about briefly in the book, the Fascio family, even if sometimes it’s spelled Facio. This man, Amerigo Fascio, in the 1880 census is listed as white. He and his entire family are listed as white. This is another case similar to when marriage licensing officers who read bodies and make determinations. Because the way the census worked in this time period is that census enumerators are going door to door, they're the ones that are making the racial determinations: they're not asking you what is your race, they're reading your body and writing down what race they see. Amerigo was born in Louisiana, but his father was born in Italy. Well, in the next census, the one of the year 1900, he and his entire family are listed as black. And then in the 1910 census, his son's family is listed as mulatto and then I start following his son who, in the 1920 census, is listed as black, but has a WWI draft registration card where he is listed as white.

There’s a number of things that could be going on here. Different people are making different racial assessments. Maybe he was allowed to check white on his registration card whereby census enumerators are making different racial determinations. Maybe one person opens the door and the census enumerator makes the racial assumptions for the entire family based off of this one person. But it's really fascinating to me that an Italian family on official documents can appear making such a transient racial change. I actually can imagine and see the family moving across town listed as white, but then the son is black, then mulatto, and then white again. Because they're Italian, their race can be moved back and forth across this line. I think I'll probably and hopefully turn this story into a paper.

This is very interesting. First of all, because I'm almost laughing while thinking about someone called Fascio, which recalls the fascist party to me, who from white “becomes” black. But I think that there’s more. Maybe I'm wrong, but in this virtual positioning in the midst of two precise and identified races and in the subsequent transition between feeling and sometimes even declaring oneself before white and then black, it seems to me that I can perhaps perceive some traits of what happens, obviously with all the differences, in the perception of one's sexual identity today... Actually, you used the word “binary” before, and now you used the word “transient”. Am I completely wrong?

What I definitely see happening historically is that there is a racial movement. And so the fact that southern States are trying to impose these very fixed racial categories, and the lived experience didn't operate that way: and very much I see the Italians moving between them, sort of complicating the situation. That's why I talked about this idea of transiency. But these categories were not static, they were actually more fluid than lawmakers wanted them to be: this is why I really wanted to emphasize the movement that's going on between all of these categories. I think in terms of the contemporary maybe we'll get there, but I don't know how much of it translates into this contemporary moment.

Who was the “Privileged Dago”?

One of the other stories I follow in the book is the fact that in the 1890s Louisiana is imposing racial limitations on who can vote. They start by discussing a sort of a literacy requirement for voting, a number of ways to limit voting that will not be in violation of the 15th Amendment, which says you cannot limit someone's right to vote based on skin color. So they're basically looking at ways to eliminate black voting rights, and they talk a lot about the illiterate ones, they're trying to eliminate immigrants, poor people who are of lower classes from the right to vote.

In those years in Louisiana there is a sort of an urban/rural divide, a planters versus urban situation. And as Louisiana is passing this new voting amendment to restrict the voting, they pass a property requirement. It means that you can only vote if you have a certain amount of money or property, and an education qualification: you have to pass a literacy test. But then they also start passing clauses to allow people to vote outside of those requirements. One of the clauses ends up being dubbed the "Privileged Dago clause," which will essentially allow Italians to vote whether or not they met the property or education qualification. This has to do with the fact that there was a very powerful voting bloc of Italians in New Orleans, and the ward bosses, the Democrats, are saying “we want to make sure that our constituents can still vote because they're voting for us, and so we are going to advocate for this clause.” It ends up being given this sort of pejorative nickname because those in more rural areas or outside of the New Orleans political ring are considering this to be a way to enable Italian voters even if they don’t meet the property and education qualification. It starts in 1896 and then the Constitution is revised in 1898.

What is also pretty interesting to me is that throughout this period Italians are not just on the sidelines, they are not being passive in this: in 1896 they have a massive parade, a big meeting and then they're marching through the streets with draft horses and posters and chickens perched in cages demanding that they be allowed to vote, regardless of the voting rights laws that are passed in Louisiana. So I also find this an interesting story, because they are very much participating in this moment.

So, in the end, is it correct to say that in the South of the US the Italians, and in particular the Sicilians, have been racially profiled because of their heritage and also because of the brown tan of their skin?

Race is operating differently, in the sense that it's not just about physicality, not like we read it today. There's a race which we might think of as nationality, and then there's color. Some Italians could be seen as dark skinned even if they were not physically dark skinned, they were just perceived as dark skinned, because they were Italian.

And then there’s also the north vs south of Italy that further complicates the race puzzle. In New Orleans there was an Italian Benevolent Society in the 1840s that didn't allow Sicilians to join them. So Sicilians had to form their own Sicilian benevolent society. It’s only at the end of the century that these societies come together, and this brings a development of an Italian American sense, or at least a New Orleanian Italian American sense where these groups are coming together and they have a cake at their celebration with a picture of Dante on it, and they have an American flag and an Italian flag, and they're celebrating Garibaldi's birthday. It becomes a very interesting unification process where they're getting rid of some of those regional differences and uniting together as Italian Americans.

Is it true that Italians were particularly accustomed to consider and approach African Americans in a completely respectful way, without showing them the discrimination that other white-skinned people unfortunately had as a habitual attitude?

I think there's a couple things happening. In the 19th century race and the racial hierarchy is operating differently in Louisiana then in Italy. It's a fact that Italians and African Americans are essentially living as neighbors. In New Orleans back in those days is not like other urban centers: you have African Americans and Italians, and Germans and French, all living on the same block. And you also have Italians who, after they start moving into the business sectors, are going to open up businesses targeted to black communities. And I don't think that it's necessarily because they were more respectful, but they're seeing an available business not being in competition with white grocery stores. But this will lead further to this commingling. I think that there's something about the fact that they do see race operating differently and they're behaving in a way that is going to be seen as potentially contrary to Jim Crow mandates of the time period.

In the light of what you have studied and written for several years, and what you have been so kind as to tell our readers here today, how is it possible and what can be done to counteract the fact that today, through the attacks against Columbus, someone is trying to assert an alleged opposition between the Italian American and African American communities?

This is a very complicated question and there's a lot of things going on.. I think it's unfortunate that this has become sort of a red herring, where we have this interracial/interethnic conflict going on when the real issue is systemic racism. I haven't done much research yet on Columbus Day, I will say that I am starting down that path because my next work is looking at Italians in Colorado, which is the other major site of lynching of Italians in the US. And this is also the State that founded the first Columbus Day, although in a very active anti-Catholic environment. That's the story that I'm going to be working on next, now that I'm in Colorado.

In un periodo in cui dobbiamo ancora dolorosamente constatare quanto la questione razziale sia una ferita aperta nell'evoluzione degli Stati Uniti d'America e una urgentissima situazione da cercare di risolvere, il nostro cuore italiano innamorato dell'America è scosso anche dai pretestuosi e sbagliati tentativi di promuovere ostilità tra le comunità afroamericane e quelle italiane.

La storia degli italiani nel sud degli Stati Uniti racconta come se c'è un gruppo etnico non di colore che ha ricevuto umiliazioni, discriminazioni, stereotipi e violenze niente affatto comparabili in termini numerici rispetto agli orrori che sono stati messi in atto contro gli afroamericani, ma non per questo meno gravi, bè quel gruppo etnico è quello italiano. Sono storie interessanti e dolorose, che nessuno ha il diritto di dimenticare o negare o, ancora peggio, manipolare per attuali motivi ideologici. E' per questo che ringraziamo molto la Professoressa Jessica Barbata Jackson, autrice di un fondamentale volume per capire questi temi: Dixie's Italians: Sicilians, Race, and Citizenship in the Jim Crow Gulf South

Professoressa, prima di tutto ci parli delle sue origini italiane. Da quale regione italiana viene la sua famiglia?

I miei bisnonni erano italiani, di un piccolo paese, Ginestra degli Schiavoni in provincia di Benevento in Campania. Mio nonno è nato negli Stati Uniti. Il mio bisnonno, Terigio, immigrò intorno al 1910, prima a Ellis Island e poi nella Bay Area vicino a San Francisco. Erano in realtà Barbato, in origine, ma c'è stato un errore a Ellis Island, e sulla carta sono diventati Barbata. L'Italia è l'unico posto dove non ho mai dovuto fare lo spelling del mio cognome da nubile.

Mio padre è cresciuto negli anni '50, in un ambiente dove c’era una spinta all'americanizzazione: non è cresciuto circondato da grandi tradizioni italiane, e quindi non è stato necessariamente qualcosa che mi è stato trasmesso più direttamente. Però poi io ho studiato a Firenze quando ero all'Università e poi ho insegnato inglese per alcune estati in Italia a bambini delle scuole italiane. Così credo di aver cercato di recuperare l'accesso alle mie origini italiane attraverso i miei viaggi e le mie esperienze di lavoro e poi con la mia ricerca.

Come e perché ha deciso di scrivere Dixie's Italians: Sicilians, Race, and Citizenship in the Jim Crow Gulf South?

Prima di iniziare la scuola di specializzazione per diventare professore di storia, ero un insegnante di storia al liceo. Sono sempre stata molto affascinata dalla storia dell'immigrazione, in generale. Quando ho iniziato la scuola di specializzazione, non avevo molta familiarità con la storia di come gli italiani sono “diventati bianchi”. E quando ho iniziato a fare ricerche, c'era già molta letteratura su questo argomento, ma mancava qualcosa. C'era la storia dell'immigrazione della terza ondata negli Stati Uniti tra il 1880 e il 1920, concentrata su Boston e New York e Chicago. Generalmente pensiamo a questa esperienza immigratoria solo verso questi porti urbani. Ma stavo leggendo, per un altro corso, alcuni libri sulla prima New Orleans in Louisiana, e sono rimasta affascinata da come funzionava il concetto di razza e l’esperienza multirazziale stratificata in Louisiana. Mi sono imbattuta nella storia del linciaggio del 1891 di 11 italiani a New Orleans, uno dei più grandi linciaggi di massa nella storia degli Stati Uniti. E così quella è stata una sorta di storia di apertura per il mio lavoro di tesi. Ho cominciato a rendermi conto che c'erano tre diversi tipi di storie che stavo esaminando: la storia dell'immigrazione, la storia razziale del Sud/Louisiana e la storia italiana moderna, e sovrapporle l'una all'altra è diventato davvero affascinante.

In primo luogo è stato un recupero di storie che non avevamo mai sentito prima, alcune di queste esperienze di linciaggio, le esperienze di voto degli italiani nel sud: c'è un'esperienza razziale complicata già in corso in Louisiana, a causa della presenza francese e spagnola.

Poi abbiamo avuto le leggi di Jim Crow che sono state imposte in questo periodo, le leggi di segregazione, lo sforzo di imporre nel il Sud questa binarietà bianco-nero, quando ci sono gli italiani che sono un po' nel mezzo, una sorta di esperienza razziale "grigia". Quindi cosa succede quando gli italiani arrivano in quella che dovrebbe essere una struttura razziale binaria?

E poi mi ha davvero molto affascinato portare la narrazione del Risorgimento italiano e dell'unificazione e il fatto che il 90% degli immigrati di cui leggevo, a New Orleans, erano in realtà siciliani. Questo ha portato tutta un'altra storia complicata nell’analizzare questa contrapposizione nord contro sud degli italiani, le identità regionali che questi immigrati stavano portando: erano siciliani, non parlavano italiano, eppure erano chiamati italiani. Quindi ho mescolato insieme queste tre diverse storie di immigrazione nella mia tesi di laurea, che poi è diventata questo libro.

Ci sono differenze tra le storie dell'emigrazione italiana e siciliana in Louisiana e quelle in altre parti del Sud?

Sì, c'è una differenza. Metterei Mississippi e Alabama in una unica categoria, perché non anche se non ci sono linciaggi in Alabama, ho alcune storie che si svolgono in questo Stato. La differenza è che la più grande popolazione italiana è in Louisiana e comincia a diffondersi prima a New Orleans e poi nelle piantagioni di tutta la Louisiana. Ma la differenza più grande è che New Orleans è una città creola molto cosmopolita. E dico creola nel senso che c'è una molteplicità di razze che si uniscono al patrimonio culturale francese e spagnolo. Quando guardiamo a come gli italiani sono percepiti a New York, l'anti-cattolicesimo è in realtà una grande parte di ciò che guida alcuni dei sentimenti anti-italiani. Ma questo non è affatto il caso di un posto come New Orleans, dove c'era una maggiore accettazione del cattolicesimo, una maggiore accettazione di questi diversi gruppi che si incontravano. E direi che questo non è ciò che accade in Mississippi e Alabama.

Così il sentimento anti-italiano nelle storie che ho seguito in Mississippi grazie ad alcuni ricercatori italiani, in realtà riguarda l'anti-cattolicesimo: uno sforzo per allontanare gli italiani cattolici, insieme al movimento del Ku Klux Klan in Mississippi che ha una delle sue forze trainanti appunto nell’anti-cattolicesimo. Le differenze sono in parte dovute alla demografia, perché gli italiani lavorano in settori industriali diversi, ma sono anche dovute alla loro capacità di integrazione: ecco perché il sentimento anti-italiano è guidato da fattori molto diversi in Louisiana rispetto a quelli del Mississippi. Nel Mississippi gli italiani lavoravano nell'industria del legname, mentre a Birmingham, in Alabama, nell'industria mineraria. Ma se guardiamo le relazioni tra italiani e persone di colore a New Orleans, è uno scenario molto diverso da quello dell'Alabama e del Mississippi.

Parliamo dei linciaggi. È già abbastanza grave che non tutti conoscano la storia di quello del 1891 a New Orleans, ma ce ne sono stati altri che sono praticamente sconosciuti a chi non ha letto il suo libro....

Vero. Circa due dozzine di italiani sono stati linciati nel Sud in questo periodo di tempo, anche se, naturalmente, in nessun modo questo si avvicina alla storia dei linciaggi dei neri americani. Nove linciaggi su dieci riguardano i neri americani, ma per me è molto sorprendente che gli italiani siano gli unici europei che sono stati linciati in gran numero. Così anche quando guardiamo fuori dal Sud, e guardiamo altri luoghi in cui ci furono linciaggi come l'Ovest, il Texas, anche il Colorado, le vittime di linciaggio sono neri americani, nativi americani, indigeni, messicani, cinesi e italiani.

Perché è successo? Perché questo particolare gruppo è stato reso abbastanza “non bianco” da poter diventare oggetto di una violenza molto razziale come quella dei linciaggi? Ho esaminato specificamente i linciaggi in Mississippi e in Louisiana, e poi ho cercato di scoprire il contesto di tempo e di luogo. O meglio, cercando di capire perché gli italiani vennero linciati, ho scoperto che c'erano fattori molto contestuali in ognuno di questi linciaggi.

Parte del ragionamento che ho cercato di fare è che non è che gli italiani vengono linciati specificamente perché sono italiani; ma il fatto di essere italiani, li mette nelle condizioni di poter essere linciati. E poi è il contesto di tempo e luogo che porta a queste particolari forme di violenza. Così nel 1896, a Hahnville, in Louisiana, tre italiani, siciliani in realtà, vengono linciati. Due di loro, solo perché si trovavano in prigione nel momento in cui un importante cittadino della Louisiana era stato ucciso. E anche se la persona accusata di averlo ucciso era in prigione, finiscono per linciare tutti e tre questi siciliani.

Poi la Louisiana nel 1899: qui sono cinque i siciliani che vengono linciati. E la storia qui è davvero complicata. Tre di loro sono fratelli. Sono accusati di aver ucciso un medico della città, anche se alla fine il medico sopravvive. Forse c'è qualche paura di concorrenza economica. Quindi è quasi come se i linciaggi non avvenissero perché questi uomini sono italiani, o siciliani, ma perché si trovano in situazioni in cui potrebbero essere colpevoli di qualcosa a causa della loro situazione economica, ma non perché sono italiani.

Sono sempre stato molto affascinato dalla storia del reato di “miscegenetion” (il reato di mescolanza razziale) e in particolare dalla storia di Jim Rollins, anche perché avviene incredibilmente nel 1922, lo stesso anno in cui in Italia va di moda la promozione del nostro Paese come nazione bianca forte...

La storia vera e propria è un po' più complicata di come la si racconta. Dunque Jim Rollins è un uomo afroamericano, lui e Edith Labue, una donna bianca, hanno una relazione consensuale. Il marito di Edith parte per combattere nella prima guerra mondiale. Poi torna e lei è incinta: potrebbe essere il figlio del marito, ma forse no.

Tutta la questione della miscegenetion è una legge che dice che non puoi sposare qualcuno di una razza diversa dalla tua, ma non è che la polizia vada in giro a cercare queste relazioni: indagheranno solo sulle cose che vengono segnalate. Quindi qualcuno avrebbe dovuto segnalare questa situazione. Ciò che le leggi sul matrimonio stanno cercando di fare in questo periodo è regolare le relazioni visibili, piuttosto che necessariamente il sesso o l'intimità interrazziale. Ci sono molte relazioni interrazziali durante tutto il XIX secolo, tra padroni di schiavi e persone schiavizzate, e la legge sta cercando di rendere invisibili queste relazioni pubbliche.

Comunque, la polizia arriva e irrompe in casa Labue, e trova Jim Rollins e Edith Labue in una stanza sul retro, non una camera da letto, ma apparentemente una stanza al buio: hanno tutti i vestiti addosso, ma li arrestano. Entrambi vengono arrestati. Quindi anche Edith Labue viene arrestata per aver violato le leggi sulla miscegenetion. A questo punto, quando avviene l'arresto, credo che il bambino sia già nato, perché poi il bambino appare nel processo. Ci sono alcune prove che la polizia ha estorto una confessione a Jim Rollins, brandendo un'arma, e lo ha costretto a confessare di aver avuto una relazione con Edith Labue.

Sono entrambi condannati. E così anche Edith Labue va in prigione. Non mi è chiaro cosa le succede esattamente, e non sono riuscita a trovare molti documenti su di lei, ma viene rilasciata qualche mese dopo. Questo succede nel 1921. Nel 1922, Jim Rollins ricorre in appello, ed è qui che la cosa diventa un po' complicata. La maggior parte degli studiosi e degli storici si limita a leggere il riassunto della sentenza d'appello: sì, la sua condanna è annullata, perché si legge nel riassunto che Edith Labue non è considerata una "donna bianca", e quindi non aveva violato la legge della miscegenetion. Ma io ho approfondito, con l'aiuto di un altro storico che ha effettivamente utilizzato le trascrizioni del tribunale, e penso che le trascrizioni raccontino una storia leggermente diversa.

Nelle trascrizioni del tribunale, quando stanno valutando se Jim Rollins abbia o meno violato la legge, la loro unica prova è il terzo figlio di Edith Labue, e in realtà portano il bambino in aula tre volte diverse e parlano di come il bambino abbia i capelli crespi e di come abbia la pelle più scura. Non abbiamo prove fotografiche del bambino, quello che sappiamo è quello che dicono: le trascrizioni del tribunale non dicono né sì né no. Parlano del fatto che il bambino è diverso dai due figli più grandi di Edith Labue.

Il marito di Edith Labue è un testimone dell'accusa, quindi in realtà sta testimoniando contro sua moglie, e dice anche che lui non è siciliano, che non è mai stato in Africa. Sta davvero cercando di prendere le distanze dall'essere italiano del sud e sostiene che sua moglie è forse originaria di qualche luogo vicino al centro Italia. Sta cercando di sostenere che lei è bianca, cercando specificamente di separare se stesso e sua moglie dall'essere italiani del sud. Quindi c'è sicuramente questa discussione in corso tra l'essere italiano del Nord e italiano del Sud. Dal 1908 circa e per almeno un decennio, i rapporti del censimento americano identificano il Nord Italia e il Sud Italia come paesi diversi e persino razze diverse. Quindi il marito di Edith sta cercando di sostenere che lei è un'italiana del centro Italia, non è questa sorta di sospetta italiana del sud, siciliana, e quindi che lei ha, di fatto, violato la legge della miscegenetion.

Non è chiaro cosa succede dietro le porte chiuse, ovviamente, ma il giudice finisce per decidere che l'accusa non ha provato il suo caso, perché un solo singolo atto di sesso interrazziale non viola la legge, e che ci deve essere la prova di una relazione continua. Questo, per me, è ciò che finisce per ribaltare la sentenza: che l'unica prova che avevano era questo bambino e quindi avevano solo la prova che forse c'era stata una relazione interrazziale una volta, ma che non avevano necessariamente la prova, o non erano in grado di provare, che c'era una relazione continua. Ma questo non rende la storia meno sorprendente.

Non lo leggo come se Edith Labue fosse sospettata di non essere bianca, perché non valutano la sua razza nello stesso modo in cui fanno in altri casi interrazziali o di miscegenetion. Quando i tribunali valutano la razza di una persona, la determinano in base alle interazioni e ai comportamenti personali, quindi dicono qualcosa come: "Beh, è andata alla chiesa della comunità nera e ha invitato queste persone a casa sua. Quindi deve essere non bianca". Non stanno analizzando e valutando la sua razza nello stesso modo che vedo in altri casi di miscegenetion. Quindi non penso necessariamente che sia una prova che si sia negato il suo essere bianca. Ma c'è sicuramente in gioco una narrazione nel contesto siciliano / italiano del sud / italiano del centro-nord. E questa è la prova del fatto che c'è questa conversazione in corso su questa sorta di "in betweenness", l'area razziale "grigia" degli italiani del sud. Lo trovo assolutamente affascinante.

Ci sono aneddoti simili a quello di Jim Rollins che possono essere raccontati ai nostri lettori per spiegare ulteriormente la situazione degli italiani nel Sud degli Stati Uniti?

Il quinto capitolo del mio libro riguarda questi casi di miscegenetion, fino a che punto gli italiani si sposano con persone di colore, e ho trovato casi in cui, anche in Louisiana, anche quando una relazione sarebbe stata illegale secondo le leggi matrimoniali dello Stato, ci sono prove di un uomo italiano e una donna di colore che avevano una licenza di matrimonio. Questo significa che lo Stato ha convalidato questa relazione, ha sancito la sua ufficialità, quindi stanno considerando questo uomo italiano come abbastanza non bianco da poter avere una licenza di matrimonio con questa donna di colore. Non stanno solo vivendo insieme, hanno ricevuto la licenza ufficiale per avere un matrimonio legale, anche se a bianchi e non bianchi non era permesso sposarsi.

Potrebbe essere un caso di misoginia? Voglio dire, potrebbe essere che a quei tempi un uomo bianco era autorizzato ad avere una relazione con una donna nera, perché oltre al diverso trattamento delle persone in base al colore della loro pelle, c'è anche che le donne non erano trattate allo stesso modo?

Sì, potrebbe essere qualcosa del genere. Tutto questo avviene a livello molto locale. Quindi, sì, ci sono delle leggi, ma è l'impiegato incaricato di rilasciare le licenze di matrimonio che considera il colore della pelle e prende le decisioni. Certamente gli uomini bianchi hanno più "prerogative" per fare ciò che vogliono: ma è raro in questo periodo in cui vengono imposte le leggi di Jim Crow e queste leggi sul matrimonio, che agli uomini bianchi, indipendentemente dall'essere italiani o non italiani, possa essere concessa una licenza legale se ciò è in violazione delle leggi sul matrimonio dello Stato.

Un altro fenomeno che ho scoperto è quello delle famiglie italiane che cambiano razza. Ce n'è una in cui mi sono imbattuto e di cui parlo brevemente nel libro, la famiglia Fascio, anche se a volte si scrive Facio. Quest'uomo, Amerigo Fascio, nel censimento del 1880 è elencato come bianco. Lui e tutta la sua famiglia sono elencati come bianchi. Questo è un altro caso simile a quello degli impiegati delle licenze di matrimonio che guardano le persone e decidono in base a quello che vedono. Perché il modo in cui il censimento funziona in questo periodo è che gli incaricati del censimento vanno porta a porta, sono loro che fanno le determinazioni razziali: non ti chiedono qual è la tua razza, ti guardano e scrivono quale razza vedono. Amerigo è nato in Louisiana, ma suo padre è nato in Italia. Bene, nel censimento successivo, quello del 1900, lui e tutta la sua famiglia sono elencati come neri. E poi nel censimento del 1910, la famiglia di suo figlio è elencata come mulatta e poi comincio a seguire suo figlio che, nel censimento del 1920, è elencato come nero, ma ha una carta di registrazione della prima guerra mondiale dove è elencato come bianco.

Ci sono diverse cose che possono essere successe, in questo caso. Persone diverse stanno facendo valutazioni razziali diverse. Forse al figlio di Amerigo viene permesso di identificarsi come bianco sulla sua carta di registrazione nel 1920, per cui diversi impiegati stanno dando diverse determinazioni razziali. Forse una persona apre la porta e l'incaricato del censimento fa le sue supposizioni razziali per l'intera famiglia basandosi su questa sola persona. Ma è davvero affascinante per me che una famiglia italiana su documenti ufficiali possa risultare transitoriamente da bianca a nera. In realtà posso immaginare la famiglia che si trasferisce dall'altra parte della città elencata come bianca, ma poi il figlio è nero, poi mulatto, e poi di nuovo bianco. Poiché sono italiani, la loro razza può essere spostata avanti e indietro attraverso questa linea. Spero di trasformare questa storia in un futuro paper.

Questo è molto interessante. Prima di tutto perché mi viene quasi da ridere pensando a uno che si chiama Fascio, che mi ricorda il partito fascista, che da bianco "diventa" nero. Ma credo che ci sia di più. Forse mi sbaglio, ma in questo posizionamento virtuale in mezzo a due razze precise e identificate e nel successivo passaggio tra il sentirsi e talvolta anche il dichiararsi prima bianco e poi nero, mi sembra di poter forse percepire alcuni tratti di quello che accade, ovviamente con tutte le differenze, nella percezione della propria identità sessuale oggi... In realtà, prima lei ha usato il concetto di "binarietà", e ora ha usato la parola "transitoriamente". Mi sbaglio completamente?

Quello che sicuramente vedo accadere storicamente è che c'è un movimento razziale. E così vedo il fatto che gli Stati del sud stiano cercando di imporre queste categorie razziali molto fisse, e che l'esperienza vissuta non ha funzionato in quel modo: e vedo gli italiani che si muovono tra queste categorie, complicando un po' la situazione. Ecco perché ho parlato di questa idea di transitorietà. Ma queste categorie non erano statiche, erano in realtà più fluide di quanto i legislatori volessero descriverle: ecco perché volevo sottolineare il movimento che avviene tra tutte queste categorie. Penso che in termini di contemporaneità forse ci arriveremo, ma non so quanto di ciò si traduca in questo momento contemporaneo.

Chi era il " Privileged Dago "?

Una delle altre storie che seguo nel libro è il fatto che nel 1890 la Louisiana sta imponendo limitazioni razziali su chi può votare. Iniziano a discutere una sorta di requisito di alfabetizzazione per il voto, una serie di modi per limitare il voto che non violino il 15° emendamento, che dice che non si può limitare il diritto di voto di qualcuno in base al colore della pelle. Quindi stanno fondamentalmente cercando modi per eliminare il diritto di voto dei neri, e parlano molto del concetto di analfabetismo, stanno cercando di eliminare gli immigrati, i poveri che sono di classi inferiori dal diritto di voto.

In quegli anni in Louisiana c'è una sorta di divisione urbana/rurale, una situazione di lavoratori nelle piantagioni contro impiegati urbani. E mentre la Louisiana approva questo nuovo emendamento per limitare il voto, approva un requisito di proprietà. Significa che si può votare solo se si ha una certa quantità di denaro o di proprietà, e un requisito di istruzione: si deve superare un test di alfabetizzazione. Ma poi cominciano anche ad approvare clausole per permettere alle persone di votare al di fuori di questi requisiti. Una di queste clausole finisce per essere chiamata la clausola del “Privileged Dago", che permetterà essenzialmente agli italiani di votare indipendentemente dal fatto che abbiano o meno i requisiti di proprietà o di istruzione. Questo ha a che fare con il fatto che c'è un blocco di voto molto potente di italiani a New Orleans, e i capi delle circoscrizioni, i democratici, dicono "vogliamo essere sicuri che i nostri elettori possano ancora votare perché votano per noi, e quindi sosterremo questa clausola". Finisce con l'avere questo nome peggiorativo perché quelli delle zone più rurali o fuori dal giro politico di New Orleans lo considerano un modo per abilitare gli elettori italiani anche se non hanno i requisiti di proprietà e istruzione. Inizia nel 1896 e poi la Costituzione viene rivista nel 1898.

La cosa interessante per me è che in tutto questo periodo gli italiani non sono in disparte, non sono passivi: nel 1896 fanno una grande parata, una grande riunione e poi marciano per le strade con cavalli da tiro e manifesti e polli nelle gabbie chiedendo il diritto di votare, indipendentemente dalle leggi sui diritti di voto che vengono approvate in Louisiana. Quindi trovo anche questa una storia interessante, perché stanno partecipando molto a questo momento.

Quindi, alla fine, è corretto dire che nel Sud degli Stati Uniti gli italiani, e in particolare i siciliani, sono stati profilati in maniera razzista a causa delle loro origini e anche per il colore più scuro della pelle di alcuni di loro?

La razza funziona diversamente, nel senso che non si tratta solo di fisicità, non come la leggiamo oggi. C'è una razza che potremmo pensare come nazionalità, e poi c'è il colore. Alcuni italiani potevano essere visti come scuri di pelle anche se non erano fisicamente scuri di pelle, erano solo percepiti come scuri di pelle, perché erano italiani.

E poi c'è anche il nord contro il sud dell'Italia che complica ulteriormente il puzzle della razza. A New Orleans c'era una Italian Benevolent Society nel 1840 che non permetteva ai siciliani di farne parte. Così i siciliani dovettero formare una propria società siciliana di beneficenza. È solo alla fine del secolo che queste società si riuniscono, e questo porta allo sviluppo di un senso italoamericano, o almeno un senso italoamericano “New Orleans style”, dove questi gruppi si riuniscono e quando festeggiano hanno una torta con una foto di Dante, e hanno una bandiera americana e una italiana, e celebrano il compleanno di Garibaldi. Diventa un processo di unificazione molto interessante dove si liberano di alcune delle loro differenze regionali e si uniscono insieme come italoamericani.

È vero che gli italiani erano particolarmente abituati ad avvicinarsi agli afroamericani in modo del tutto rispettoso, senza mostrare loro la discriminazione che altre persone dalla pelle bianca avevano purtroppo come atteggiamento abituale?

Credo che ci siano un paio di cose che accadono. Nel XIX secolo la razza e la gerarchia razziale funziona diversamente in Louisiana che in Italia. È un fatto che italiani e afroamericani vivono essenzialmente come vicini di casa. A New Orleans in quei giorni non è come in altri centri urbani: hai afroamericani e italiani, e tedeschi e francesi, che vivono tutti nello stesso isolato. E hai anche italiani che, quando iniziano a muoversi nei settori commerciali, aprono attività mirate alle comunità nere. E non penso che sia necessariamente perché sono stati più rispettosi, ma vedono un business disponibile non essendo in competizione con i negozi di alimentari bianchi. Ma questo incrementerà ulteriormente questa commistione. Penso che ci sia qualcosa nel fatto che vedono la razza operare in modo diverso e si stanno comportando in un modo che sarà visto come potenzialmente contrario alle leggi di Jim Crow di quel periodo.

Alla luce di quello che lei ha studiato e scritto per diversi anni, e di quello che è stata così gentile da dire ai nostri lettori qui oggi, come è possibile e cosa si può fare per contrastare il fatto che oggi, attraverso gli attacchi contro Colombo, qualcuno stia cercando di affermare una presunta opposizione tra la comunità italoamericana e quella afroamericana?

Questa è una questione molto complicata e ci sono molte cose in ballo. Penso che sia un peccato che questo sia diventato una sorta di depistaggio, dove abbiamo questo conflitto interrazziale/interetnico in corso quando il vero problema è il razzismo sistematico. Non ho ancora fatto molte ricerche sul Columbus Day, sto iniziando a seguire questa strada perché il mio prossimo lavoro riguarda gli italiani in Colorado, che è l'altro grande luogo di linciaggio degli italiani negli Stati Uniti. E questo è anche lo Stato che ha fondato il primo Columbus Day, sebbene in un ambiente anticattolico molto attivo. Questa è la storia su cui lavorerò prossimamente, ora che sono in Colorado.