Al Guerriero (Author of the book "From Fra Angelico to Frankie One Eye: An Examination of Italian American Nicknames and Identity in the 21st century")

Un esame dei soprannomi e dell'identità italoamericana nel ventunesimo secolo

In today's world, language is something extremely delicate. Whether it is good or bad, we gladly leave it to the readers' judgment. What is certain is that sensitivity is definitely higher than it used to be.

Italian Americans have always been the object of nicknames and monikers that have never been positive, affectionate or friendly, as it could often happen if such were the intentions of those who use them. A nice book has just come out that analyzes this theme, From Fra Angelico to Frankie One Eye: An Examination of Italian American Nicknames and Identity in the 21st century. We welcome its author, Alfonso "Al" Guerriero, whom we thank for being on We the Italians.

Al, please let’s start with something about you. What’s your Italian American story?

My background and the impetus behind my book’s thesis of nicknames and identity in the 21st century, has several layers.

First, I have noticed through the years that more and more people in the United States identify themselves as American. I think their reaction is great because most social scientists will agree that ethnicity does not have any particular social construct: it cannot be measured, and so in essence, the best way to define ethnicity is that we each make our own choice depending on our life experiences. Having said that, I, on the other hand, have always identified myself as an Italian American. Since I have always identified myself this way, there are Americans who question this way of thinking. They believe because I was born in America (NYC) I, and anyone else who subscribes to the hyphenated American concept, is not being true to America.

In 1915, President Theodore Roosevelt strongly declared that “The hyphenated American is un-American.” I completely disagree with this statement. He said this during a time when nativists really controlled the rhetoric in America. Several years later in 1924 and 1927 the Immigrant Quota Acts were passed in the United States, targeting Southeastern Europeans including Italians. Today, Italian Americans are integrated.

Now, I think that when you are a child of an immigrant (my father was born in Mugnano del Cardinale in the province of Avellino, Campania) you also live the immigrant experience, which leads to the hyphenated idea. I grew up in an area in Manhattan known as the Lower East Side. I lived in a predominantly Hispanic community and attended public school where it was very diverse. My friends mainly identified as the hyphenated American. We referred to one another as Irish American, Polish American etc.

Second, when I was growing up there was a duality of cultures. My cultures were constantly colliding. What I mean is, my father was from Italy, and whenever I (and my brother and sister) visited my relatives in Italy, they referred to us as ‘Merican (Neapolitan word for American): this is where my interest about nicknames began. In front of our relatives, we were American not Italian. Returning to America, my friends referred to me as Italian or gave the slang term of Greaseball even though it was, at the time, a term of endearment.

The other layer to your question is that growing-up in New York City (and America), the image of Italian Americans, for a young person, was challenging. I was trying to understand my role in the society as an Italian American. There were, and still is, constant stereotypes of organized crime figures. In America, Italian Americans have the constant albatross around our necks related to the Mafia. The media and the movies constantly perpetuate this concept. Also, there were popular television sitcom characters in the late 1970, 1980s and 1990s, like Welcome Back Kotter where John Travolta portrayed Vinnie Barbarino. His character was a womanizer and not very bright. Then there was Happy Days, and the character’s name was Arthur Fonzie Fonzarelli. He was a former gang member who was also not very bright. In the 1990s the very popular show Friends had an Italian American character, Joey Tribbiani, who had similar characteristics as the aforementioned.

Finally, and more importantly, in NYC - at least in the 1980s - Italian American boys had the highest high school drop-out rate among white European boys in New York City and the United States. We did not appear to have respect. How was this possible in a group that gave the world Cicero, Dante, Galileo, Marconi, Pirandello? We were reduced and perceived as Goodfella Goons, or the brunt end of jokes. This all led to a lingering question for me, which was, “What does it mean to be Italian American in the 21st century? Now, of course most in America would say, Italian American identity is defined by the 3F’s: family, food and faith. So, I asked myself: what else can be said about the Italian American identity that have not been already mentioned?

Is this how you got the idea to write a book about Italian American nicknames?

One day I had an epiphany. I am part of the American Society of Geolinguistics, founded in 1965 by an Italian Professor and linguist from Columbia University, Mario Pei. It is an academic non-profit organization that studies anything related to world languages. So I noticed most of what I wrote was about the subject of Italian and Italian American nicknames.

I began to realize that monikers must also be considered, when defining the ethnicity. If language is part of culture, then nicknames become part of the group’s culture. Now, before I go any further let me say that nicknames are a prominent feature in all languages. The difference is that Italian monikers are known worldwide and are a major part of its ethnicity. For example, the concept of monikers in Western Culture goes as far back as Ancient Rome. Before talking about the subject of nicknames, however, let me say something about the subject of surnames.

There were generally 4 categories that contributed to a family’s last name.

- patronymic Fra Angelico name is Guido di Pietro (Guido the son of Peter). We have this in English: Johnson, Peterson, Williamson.

- toponymic (place name) Leonardo da Vinci. Leonardo from the town of Vinci or another famous individual, Jesus of Nazareth.

- occupational Italian surnames like Sarto, Ferrero. In English we have surnames like Blacksmith, Miller, or Carpenter.

- nickname Based on physical characteristics, personality traits or reputation. In the Italian last names Russo, most likely someone in the family had red-hair. An unpopular Italian surname that one of my friends had was Giovansanto (meaning young saint): someone in the family was pious and displayed saintly characteristics.

In Latin, as I am confident you know, there was the tria nomina (3 names) or agnomina, generally reserved for the Roman aristocracy and especially generals victorious in their military campaigns. Usually, these last names were a moniker. Examples include in bold: Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus; Marcus Tullius Cicero; Gaius Julius Caesar.

The idea of surnames is somewhat lost during the fall of Rome in 476 AD, as barbarians take over the country. But even with that, the idea of different words outside of Latin floats around in Italy during this time. I traced my name Alfonso to the Germanic word hidelfuns (noble member).

Then during the Italian Renaissance surnames return. An example is in the De Medici family: Cosimo (il Vecchio), Lorenzo (il Magnifico). This is thanks to Giorgio Vasari in 1550, who wrote profiles about many of these artists and included their nicknames like Giotto, Donatello, Tintoretto, Ghirlandaio, Masaccio and so many more.

With any research one notices patterns and I noticed in my case study about Italian Renaissance artists the following seven categories

- physical characteristics/imperfections

- reputation

- locality

- father’s trade

- master’s adopted surname

- religious title

- hypocoristic (which means the name is modified, like Angiotto to Giotto)

My second case study for the book involved my father’s town, Mugnano del Cardinale, where many residents and families are given nicknames. The locals speak Neapolitan, and so the words are written in the language variant. Some examples are the following:

- mussepuorco (pig stout) is someone who is stoic, and shows no expression.

- Capapecora (sheep head) to describe physical characteristic.

- cap’melone (melon head) to describe a physical characteristic.

- recchia’tosta (hard ears) literally, which mean a stubborn person.

- Culostritto (tight ass) is a parsimonious person (this is one of my favorites).

I noticed most of the appellations in Mugnano del Cardinale are similes and/or metaphors related to the farm animals or food grown within the area. In some cases, the nicknames reflect the physical imperfections of individuals or families.

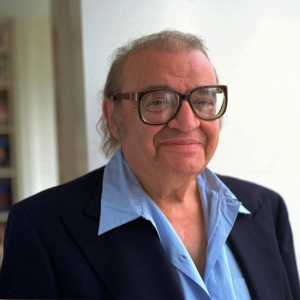

The 3rd case study in my book, Words, Puns, and Tabloid Nicknames: The Puzo/Pileggi Effect on the Language of Journalism & Italo Americans, contains quotes from an interview I organized with Nick Pileggi. His background was proven indispensable in my research. Nick Pileggi and Mario Puzo are examined as writers who influenced today’s journalism with epithets from The Godfather and Goodfellas movies.

In the aforementioned chapter, I examine the lexical borrowing of Italian words in American journalism, especially the tabloid newspapers in New York City and other English language publications. Several hundred articles about organized crime figures were examined in the New York Post and New York Daily News. The study also relied on the periodicals digital files to search for specific words related to organized crime coverage. A contributory factor in the chapter’s research was www.newspapers.com, the largest archival database of historical newspapers.

A plethora of articles and headlines was gathered to develop the most accurate analysis for the study. The chapter addresses part of the sociolinguistic aspect of Italian American identity in the 21st century and how the media’s semiotic modes, through images and text, influence America’s perception of ethnicity. Accordingly, these ethnic epithets, or neologisms, appear in newsprint, social media and television broadcasts to reinforce a particular stereotype.

Talking about your book and its title: who were Fra Angelico and Frankie One Eye?

Fra Angelico was the Italian Renaissance artist whose official name was Guido di Pietro. Giorgio Vasari gave him the nickname because his angles on canvasses were so lifelike. As to Frankie One Eye, there are several people who can claim this moniker. However, the individual I am referring to was an associate of the Philadelphia mob: he was a bookie who developed glaucoma in one of his eyes, and later was given the moniker Frankie One Eye.

Please tell us more about the role of nicknames in the formation of the Italian American identity

I believe Italian and Italian American nicknames are more popular than any other language because of the lyrical phonology that attracts most people to the name. Let us also remember the phonetic attraction of Italian names. Their forenames and nicknames have worldwide recognition. This is not to diminish the achievements of artists from other nationalities such as Dutch artists Jan van Eyck (1390-1441) or Hieronymous Bosch (1450-1516) or the German Renaissance painters Albrecht Durer (1471-1553) and Lucas the Elder Cranach (1472-1553). It is just that their names/nicknames possess harsher sounds and have less marketing appeal.

For instance, in America the creators of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, in the 1980s, understood the importance of names. One reason the animated series became a big hit in America was a direct result of names given to the characters such as Donatello, Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael. The creators of the show searched for likable names to appeal to their younger audience. The Super Mario game series was based on a similar supposition. From the Donkey Kong game, the name Mario and later his brother Luigi, sounded more appealing than its original name, Jumpman.

Recent sources indicate that the Super Mario character was named after Italian American Mario Segale who owned a warehouse in Tukwila (near Seattle, Washington) and rented the building to Nintendo. Many of the employees noticed the resemblance between Miyamoto's creation and Mario Segale, resulting in the name change. Whether it is the Ninja Turtles or Super Mario, both have introduced a new generation to the Italian names that remain relevant in the 21st century. Their popularity stems from the melodic syllables that are pleasant sounding and now familiar.

The last point to the analysis is some artist nicknames serve as a timeline in Italy’s complex and diverse history. They are symbolic of how a moniker’s original meaning unfolds from one language to the next. When examining Guido di Pietro’s (1395-1455) official name, the theory that nicknames serve as an individual marker and one’s cultural identity is uncovered. The name’s etymology evolved from Italy to America.

The name Guido represents a Latinized forename or surname that derives from the Germanic tribes’ invasion after the fall of Rome. Guido or the Germanic Wido, or Wito from widu, meaning wood; or maybe even wida, meaning far (De Felice 145, my translation), entered Italy in the 8th century AD. In medieval Italy, Germanic first and last names arrived in the peninsula. The preposition di (of) meant “son of” and was common during this era. Pietro (Peter) is a religious first name, based on one of the Twelve Apostles. Hence, Guido di Pietro tells us that Guido was the son of Peter.

Roman Catholicism usually influenced an individual’s naming practice in Italy. Another intriguing aspect surfaces when examining Guido di Pietro’s moniker. His nickname was Fra Giovanni da Fiesole, or simply later, Fra Angelico. This revealed more about the individual than his ethnicity. Fra is an Italian honorific title meaning, frater (Latin), fratello (Italian for brother) and Angelico means Angelic. Fra Angelico entered the Dominican order near Fiesole, a community outside Florence. He is well-known for his detailed paintings of angels. The examination of his moniker exposed the interests, talent, and history of the painter, as well as a brief biography.

An interesting occurrence is noticed as the cultural narrative changes with the name Guido in America. Guido went from an Italian first name to several variant last names in Italy. The name then traveled to the United States to be used as a disparaging moniker for Italian Americans. While the precise origin of the use of Guido as a derogatory term is unknown, it has historically been deployed as a way to demean Italian Americans of a working-class background.

When official names and nicknames are traced from their origins to present usage, an interesting path to a nation’s cultural and social consciousness is exposed. Curators, art historians, teachers, students and simply admirers of artists from the late 14th to 16th century marvel on the art and utter the euphonious syllables of Caravaggio, Botticelli, Fra Angelico and so many others. With this interesting analysis, how many truly realize the stories behind the immortalized nicknames that define the Italian Renaissance and Italian culture?

I understand that your book also includes short biographies and vignettes…

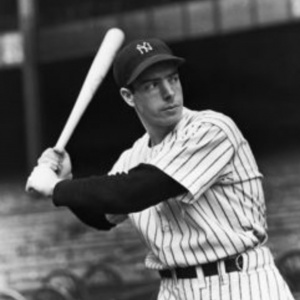

Yes, I wanted to include the idea of identity while still examining those who had nicknames. This means I wrote about my experience meeting, at 16 years old, the Italian American Baseball Player Joe DiMaggio who was an inspiration to so many Italian Americans. He had 3 nicknames: Joltin Joe, the Yankee Clipper and Joe Di. And he might be one of the few athletes in history who had 2 hit songs that mention his nicknames: Joltin’ Joe DiMaggio by The Les Brown Band (1941) and Paul Simon’s hit (1969) Mrs. Robinson’s lyrics "Where have you gone Joe DiMaggio … Joltin’ Joe has left and gone away.”

I then interviewed Dr. Rock Positano who was Joe DiMaggio’s confidant for the last 10 years of his life and wrote a book with his brother John Positano, Dinner with DiMaggio: Memories of An American Hero. I also interviewed Gay Talese, Ray Boom Boom Mancini, Lidia Bastianich, Basketball Coach Geno Auriemma, Claudio Del Vecchio, Tony Danza as well as other individuals who are not that popular but have a story about Italian American identity as WW II War Veteran Rocco Moretto, Taylor Taglianetti, and many more.

Did or do you have a nickname?

Yes, in American Al is short for Alfonso. In Italian my moniker is Funzi or ‘Fo: again modified version of Alfonso. My father’s family nickname in Mugnano was Cacciatore (hunter). His grandfather Alfonso Petrillo hunted, and so the nickname was passed on to a few generations. My younger daughter (I have two daughters age 9 and 7) recently became aware that her father wrote a book about nicknames, so she wanted to create her own nickname for me. She calls me Big P meaning Big Papa. I love it!

On the subject of nicknames, I have a feeling that today's society tends to take offense much more than that of yesteryear. But I also have the impression that Italian Americans have been much more patient than others in putting up with stereotypes and nastiness, even in the form of nicknames. Am I wrong?

I would say you are not wrong, but I do think this depends on the moniker and the relation that one has with the person addressing he/she/they by their moniker. Let’s remember there are benevolent sounding monikers like Honest Abe Lincoln or Silent Cal for President Calvin Coolidge, and there are pejorative nicknames, like in American we have four-eyes for someone who wears glasses or baldy someone who has lost most of their hair. Good/Bad monikers are throughout history, but it depends: I think even today the monikers among family and friends can be a term of endearment. Of course, the media can be insenstitive in given a disparaging diminutive.

You may be interested

-

'Phantom Limb': A Conversation With Dennis...

Dennis Palumbo is a thriller writer and psychotherapist in private practice. He's the auth...

-

2015 Bocce Bash!!

Please join Mia Maria Order Sons of Italy in America Lodge #2813 as we host the 2015...

-

An Unlikely Union: The love-hate story of Ne...

Award-winning author and Brooklynite Paul Moses is back with a historic yet dazzling sto...

-

Cathedral of St. John the Divine, Oratorio S...

For the first time ever, The Cathedral of St. John the Divine, in collaboration with the O...

-

Davide Gambino è il miglior "Young Italian F...

Si intitola Pietra Pesante, ed è il miglior giovane documentario italiano, a detta della N...

-

Former Montclair resident turns recipes into...

Former Montclair resident Linda Carman watched her father's dream roll off the presses thi...

-

Garibaldi-Meucci Museum to Celebrate Ezio Pi...

On Sunday, November 17 at 2 p.m., Nick Dowen will present an hour-long program on the life...

-

In sordina, l’Italia ritorna in scena al Nat...

La presenza italiana a Natpe 2016, la principale fiera Tv per il mercato Latino Americano...