Robert Barbera (Publisher of L’Italo-Americano)

L'uomo che rappresenta perfettamente il nostro motto: Two flags, One heart. In questo caso, One very big heart

At the end of the interview with Robert Barbera, who is over 80 years old, I felt like I was talking to a 20 year old boy. I was asking him about the wonderful things he has helped to create, why he is one of the largest and most generous financiers of the Italian American and Italian community not only in California, but all over the United States, and he was telling me about his future projects.

Interviewing a person like Robert is one of the little big satisfactions that this adventure with We the Italians has allowed me: I can only thank him, really a lot, for all that he has done, that he does and that he will do so that these two flags are more and more united in an ever stronger heart.

Robert, what’s your story and where in Italy are your origins?

My mother was from Palermo, precisely from a little town up on a hill called Carini and my dad was from Marsala. They came to the US independently of each other and they met in Chicago. They worked in the same kind of business: my dad was a clothing designer and my mom was a seamstress. They met in Illinois, where they married, but they lived most of their lives in Brooklyn, NY. My brother was born in 1929 and then a few years later - in 1932 - I was born.

From there, my parents decided to move to Queens, so I didn’t spend so much time of my life in Brooklyn. I grew up in Queens, in the neighborhood of St. Albans, where Dad bought a corner property, a very nice house. He was doing very well in his business and we had a huge backyard where he grew fruit trees such as cherry and apple trees, and vegetables.

Unfortunately in the early 40s WWII came about and we had a very difficult time: we were Italian Americans and Italy was at war against the US. We became the pariahs of the neighborhood and it was difficult because I had an Italian life in the house and an American life outside the house. When I first started grade school, I only knew Italian. I didn’t know English. So for the first three grades I had to learn English. Fortunately it was demanded by the community and the school. But my parents couldn’t speak Italian because it was “the language of the enemy.” But we would speak it at home, even though we were told we shouldn’t even do that. Outside the house we would speak English. So it affected all of us because we had to give up our language and that’s where our culture lived; it was difficult and people would look at us as “Italians” and not in a good way.

It made the challenge to survive more acute: we had to overcome the discrimination - and we did - but growing up in that confusion was hard. School teachers were always recognizing me as an Italian. That wasn’t easy and sometimes, humiliating. My origins never really left me; they were certainly deep.

After WWII everything changed. Suddenly everybody loved Italy, what Italy had done in history or what it was known for. We were finally appreciated. I had gone through a time when I was stereotyped because I was Italian American and then a time when I was appreciated for being Italian American. All of a sudden, expectations changed. Ironically, if you were Italian you should be good at cooking, you should know how to sing ... just because you were Italian. And some of us did know how to do those things, but I don’t know how to sing and I can’t cook.

The passion for Italy was always there. My mum and my dad were always in love and passionate about their homeland. Those were the kind of things I grew up with ... the first twenty and some years of my life. But frankly, when you go into the business world, you have to be all American. But in the social world, you have to be all Italian. I found that very doable. It worked well and I did well, so no regrets.

I spent the first 21 years in NYC. I was a designer and an interior decorator in my early years. Then I was transferred to North Carolina for three years. When I finally ended up in California 1965, I was so happy because it’s the perfect state for climate and weather. I am a sunshine kid, so California just suits me perfectly. Also, the people are quite different from New York to California. In New York everything had to happen by the minute. In California everything had to happen by the hour. Speed, but also expectations were so different. Even the schools in the East expected a lot more than those in California.

When I reached my 30s I had more interest in Italian things then I did in American things and it kept growing.

You gave birth to many wonderful projects and institutions. I selected two I’d like to ask you a little bit about: Fondazione Italia and Lingua Viva.

In 1990, I was the president of Federated Italo-Americans in Southern California. In 1992, the Italian government decided to buy property in Los Angeles for a cultural institute. I was absolutely thrilled, because the best way to promote Italian culture in Los Angeles was to have a physical site—a proper location. The government bought this property in Westwood and then I was asked to help develop the property. So I rebuilt walls, classrooms, cooking facilities, a laboratory, even the restrooms. I was happy because I was involved in creating an Institute that we could be very proud of.

Then I decided to incorporate a school there and I created Fondazione Italia and Lingua Viva ... of course along with the government. Lingua Viva is an adult school where you can learn Italian culture and language, and now it’s going very well, even with the pandemic. They offer cooking classes and show movies. Everything is working great, and I am proud I was able to participate in that. We have been teaching classes there non-stop from 1994 through today. For 26 years we have been offering Italian culture at the Institute and I couldn’t do it without the wonderful directors we had over all those years. Ten to fifteen years ago they decided to add children classrooms. This has been very important, because children have to know culture and language early in life.

Lingua Viva was supported by the government, but we raised money too and we donated it to the project. So both organizations started at the Institute. I’m not involved with Fondazione Italia anymore, but I didn’t stop with Lingua Viva.

You are a College Governor at the Thomas Aquinas College in Santa Paula, CA, and last year you welcomed there and basically saved a Columbus statue taken down by Pepperdine University. First of all, thank you very much for this. Please, tell us more about that

The fifth hundredth anniversary of 1492 was coming and I thought we needed to celebrate in a very big way. So I put out a newsletter encouraging people to understand what Columbus’s landing meant. I thought a statue would be fitting. So I was busy for two years with all the planning and development. Finally, in 1992 we had the largest Italian American banquet in Los Angeles, there were 850 people at the inauguration.

The statue was unveiled at Pepperdine University in Malibu and everybody from the university was there as well as community members. It was an absolutely wonderful day and after that we built a garden around the statue. For years it became the place where boys and girls would meet, to talk on the bench nearby and just for enjoyment in the beautiful setting.

In those years there was very little murmur about Columbus and the indigenous people; everybody was better educated than now. We had an indigenous chief at the ceremony who praised the statue. Times were very different. It was - and still is - a beautiful statue. I had it built to the exact height of Christopher Columbus. I collected pictures of Columbus to make sure it looked exactly like him.

Over time things got worse for the Columbus statue at Pepperdine. Students started parading around and denigrating Christopher Columbus, making false accusations. The rebellion of the students against the statue got so terrible that three or four years ago, the University decided to take it down and put it in a storage room. The President of the University wrote a letter to each one of us contributors ... some of the wealthiest contributors to the college are Italian. And we all accepted the decision to take the statue down, because the most important thing for us was that the school to survive and not live on with this antagonism.

Pepperdine didn’t know what to do with the statue. So, the President of Thomas Aquinas College called me up and said, “Can we have the statue?” And I said, “Oh, by all means!” And listen to this: When I was at Pepperdine I made sure that the Columbus statue was pointing to the chapel of the college, which had a lot of significance for me. So, when Thomas Aquinas took the statue, I said the same thing to them: “We have to be sure that the statue is put towards the west and facing the chapel.” I think it’s significant in that it represents what Columbus stood for: going west and having a religious purpose.

You are also the publisher of L’Italo-Americano, a great bilingual news source born 112 years ago that continues today to inform about Italy and about what’s Italian on the West Coast and particularly in California. What’s in the future of this magnificent historical media?

You are right. L’Italo-Americano started more than one hundred years ago. In the early two thousands the paper was having financial problems and I couldn’t stand the idea of the paper suffering, so I started to help them.

I not only gave money, I started writing articles—for at least 3 or 4 years—on a monthly basis, sometimes even a weekly basis, about great things Italian. I was lucky enough to find a great editor, Simone Schiavinato, and he brought new energy into the paper. Little by little it became more cultural and we dropped the politics. I don’t like politics because it’s a tough, confusing and complicated game, a negative one. I wanted to bring out great things about Italy, such as places, activities, the concept of Italians and history from a different point of view. I wanted to bring humanity into the paper. This is what Italy is really about to me. Italy gives it’s the humanity to the world. Whether it’s music, art, food, lifestyle, L’Italo-Americano is all about the Italians.

Now L’Italo-Americano is online. The future of the paper depends on embracing technology. We have an enormous audience. 50,000 people look at the site a month and so when we look at the future, it is absolutely very promising. We have added a shop to the site where people can buy products from Italy and other things Italian. I have to say thank God for Simone. He’s doing a fantastic job. You can find out more at italoamericano.org.

One of your most recent achievements is the Mentoris Project: several books about Italian and Italian American great men and women. Can you please describe it to our readers?

I started the Mentoris Project because I felt that Italians and Italian Americans deserved to be known better. I imaged publishing ten books. Then I realized that we needed to do twenty books. And now we are going to put out fifty books. The people we write about—people like A.P. Giannini, Alessandro Volta, and Mother Cabrini—worked to move our civilization ahead. It is extremely important to know the contribution of Italians and Italian Americans, in any field. And it’s important to describe what these heroes did, to tell younger generations how much of what’s good in their lives comes from the inventions and the efforts of the Italians and the Italian Americans.

I chose the name Mentoris as I see these books as providing mentorship to our readers. The goal is that when someone finishes any of these books they think, “I can do something great, too.” You can see the list of all our books at www.mentorisproject.org.

This is my legacy: to improve people’s knowledge about the influence and the leadership of Italians and Italian Americans. It’s lost unless you talk about it. We always are only one generation from losing people, and I couldn’t let that happen. Our Mentoris books are written with the goal that our readers understand the development of the persons we honor. For example: What was their family like? What inspired them? When they went to school, how did they develop? What were their symbols, and who were their heroes?

Our goal is to describe these great people, but also for the Italians and the Italian Americans to continue to take pride in who they are. I don’t like the idea of us being thought of as gangsters or bad or uneducated people. Nowadays everybody talks about the bad guys, but these books show that good people from Italy left a good mark—an indelible mark—in history. So that’s why I created the Mentoris Project and it’s giving me the greatest satisfaction. We want to reach more readers and are developing a program so people can donate our books to their local libraries and schools.

From this wonderful development comes the Mentoris Project Pilot Program at the California State University in Northridge: please tell us about that.

Well, I helped establish Italian chairs at CSUN as well as at Pepperdine ... and also an Italian exchange program at Pasadena City College. But at Northridge I helped set up an Italian Language and Culture major. It is what you would think, a typical textbook major of all the things about Italy and Italians -understanding the language and the culture. But in my mind, I wasn’t satisfied. I wanted students to really understand the passion and the circumstances of Italy. So I set up a scholarship related specifically to the Mentoris Project’s books. The next step is to reach the moment when I’ll be able to say: “This pilot program worked so well that I want it spread all over the country.” We’ll use technology - videos and other tools - to bring this program to colleges, and likely high schools, all over the United States. Students will read our books and they will write essays which our panel will evaluate. The winners will be awarded with cash prizes. I expect a few thousand kids to participate. It’s a way to expose them to our books and for them to be inspired by great Italians and Italian Americans. I look forward to seeing this program take off.

Your talent, your success and your generosity make me say that you are very Italian and very American at the same time. What’s your most Italian trait, and what’s the most American one?

My passion is all things Italian. I inherited it from my parents, no doubt about it. But the business side of me is truly American. I feel that I move continuously from one to the other. I really like both parts of me and I enjoy everything I do. The funniest thing is that my American friends say I am Italian and my Italian friends say I am American. My American friends say that I talk with too much passion, that I move my hands around; my Italian friends say that in my business I am very direct.

Honestly, I wish I was more Italian, and I wish I was more American, so sometimes my Italian heart fights my American brain about what to do, but in the end they balance quite well and they even help each other. I’ve divided my time among many organizations that support both. I was branch president of the Italian Catholic Federation and UNICO. But at the same time I co-chaired West Coast funding for the Statue of Liberty. When I meet an Italian, I think that they all are my cousins. Here in the United States, I feel like I am talking to Americans and then I behave in that way. I am thankful for the fact I am a blend. One time I say something and you can bet I am Italian and two minutes later I say something else and you are sure I am American.

You may be interested

-

'Phantom Limb': A Conversation With Dennis...

Dennis Palumbo is a thriller writer and psychotherapist in private practice. He's the auth...

-

13th Annual Galbani Italian Feast of San Gen...

In September of 2002, some of Los Angeles' most prominent Italian American citizens got to...

-

2015 scholarship competition

The La Famiglia Scholarship committee is pleased to announce the financial aid competition...

-

An Unlikely Union: The love-hate story of Ne...

Award-winning author and Brooklynite Paul Moses is back with a historic yet dazzling sto...

-

Cathedral of St. John the Divine, Oratorio S...

For the first time ever, The Cathedral of St. John the Divine, in collaboration with the O...

-

Davide Gambino è il miglior "Young Italian F...

Si intitola Pietra Pesante, ed è il miglior giovane documentario italiano, a detta della N...

-

Emanuele: cervello d'Italia al Mit di Boston

Si chiama Emanuele Ceccarelli lo studente del liceo Galvani di Bologna unico italiano amme...

-

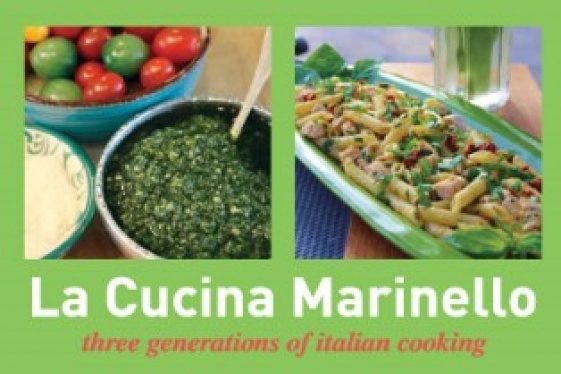

Former Montclair resident turns recipes into...

Former Montclair resident Linda Carman watched her father's dream roll off the presses thi...