Davide Ceriani (Musicologist)

Come l’Opera ha influito sullo sviluppo dell’identità italoamericana: incontriamo il Prof. Davide Ceriani

The topic we are addressing this time, among the many that trace the relationship between Italy and the United States from different angles, concerns Italian opera and the Italian Americans. Professor Davide Ceriani is a musicologist who teaches at Rowan University (Glassboro, NJ). A few months ago, he gave a multimedia presentation at the Library of Congress on how opera has impacted the development of the Italian American identity. We welcome him on We the Italians, thanking him for his availability.

Professor Ceriani, you are currently working on a project on the role that Italian opera had in the formation of the Italian American ethnic identity in American urban centers between the first wave of mass migration (1881) and World War II (1941). Please tell us how this idea came about

During my PhD in musicology at Harvard, I realized that there was a strong imbalance in the literature on Italian migration to the United States: the vast majority of academic essays focused on the socio-economic aspects of this phenomenon, while the arts were relegated to the background. There were very few references to opera, and I found this very surprising, as this art form was (and still is) one of the symbols of Italian identity abroad.

I then began exploring the role that opera had for Italian communities in America between the beginning of mass migration and Italy’s entry into war against the United States. My sources were the Italian-language magazines and newspapers published in the major urban centers of the Northeast (where the Italians were present in larger numbers); the diaries and autobiographies of the Italian immigrants; and, finally, the articles that appeared in the American press.

Even if my experience as an immigrant in the United States is completely different from that of my fellow countrymen back then, through this study project, I have tried to identify myself with their mentality and way of life. In particular, I share with them the same desire to maintain strong ties with Italy through music in general, and opera in particular.

Please tell us more about the content of your research. We know that your work has an emphasis on New York City and the Metropolitan Opera House under the management of Giulio Gatti-Casazza (1908-1935)

My research at the Met Opera (henceforth “the Met”) began in 2001 and, given the vastness of the sources available there, is not finished yet. One of my aims was to document and investigate the professional relationships between the Italian artists who worked in this opera house (singers, conductors, set designers and others) and the general manager Giulio Gatti-Casazza. The latter is one of the central figures of my study project, not only for the importance he had in transforming the Met from a pro-German to a pro-Italian institution, but also for his having managed to weave a dense network of relationships with important members of the fascist regime.

At the beginning of his tenure as manager, Gatti-Casazza had to fight against the many stereotypes that circulated about Italians. For example, as long as Italians fell into the above categories (singers, directors, set designers) the American press’s comments were mostly inclined to benevolence; on the contrary, when Gatti-Casazza was offered the opportunity to become general manager of the most important opera house in the United States, the reactions were negative. Many American music critics would have preferred to have a German manager, who at the time was identified to be Andreas Dippel. Ironically, however, this offer was made to Gatti-Casazza by Otto Kahn, an arts patron of German origins (from Mannheim), who was also chairman of the committee that financed the Met and a sympathizer of Italian opera.

At the time, what was the nature of the relationship between the people who lived in American Little Italies and Italian opera?

Sadly, for many decades, Italian immigrants and their descendants were the targets of prejudice or even open hostility. The documents show how the Italians living in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia (just to name a few) used opera as a means to legitimize themselves in the eyes of the Americans. In the process of creating their ethnic identity, the Italians and (later) the Italian Americans used opera in three ways. First, they attended live performances to show their support for the Italian singers and conductors. The articles in the American and Italian press frequently discussed the presence of our fellow countrymen in the family circle area. Second, they collectively listened to records in the homes of those few who, in the Little Italies at the beginning of the century, could afford to purchase a gramophone or other means of sound reproduction. Finally, they brought the Italian singers and conductors into the restaurants and cafes of Little Italies, as if to make them feel protected. For the second point I found countless pieces of evidence in the autobiographies and diaries I read, and for the third, I found many cartoons in both the Italian and American press.

Enrico Caruso was probably the first who, thanks to his success, gave the Italians of America the opportunity to fight back against the discrimination they were experiencing…

For Italian immigrants to the United States, the importance of Caruso went beyond the strictly musical sphere. The tenor was one of the emblems of Italian culture and embodied the success, fame, and social recognition that our fellow countrymen aspired to. Caruso was obviously proud of this role, and the many biographies written about him show how he loved to spend time with his compatriots. If, for the Italians in America, attending an Italian opera performance was a way to build a sense of community and strengthen ties with the motherland, being there when Caruso performed made the event even more special.

The enormous popularity of Italian opera in the United States instilled a strong sense of national pride in our immigrants, and Caruso’s presence reinforced this patriotic pride even further. It is important to remember, however, that Caruso’s case was not unique: the visibility of Italian impresarios, singers, and musicians in the American urban centers, where opera was staged on a regular basis, also strengthened our fellow countrymen’s self-esteem. Finally, it is worth remembering how Caruso, and other Italian figures connected to the opera world, helped the American upper and middle classes, especially in the northeast area, to reconsider the Italian migration phenomenon in a more positive light.

Is there a particular story, which not everyone knows, that you have had the opportunity to discover during your research, and one that you are pleased to share with our readers?

A story that is almost completely forgotten today, and that I found particularly interesting, concerns the composer Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari’s reception in the United States in the first half of the 1910s. Wolf-Ferrari (1876-1948) had a German father and an Italian mother, and he trained musically in both countries. Gatti-Casazza thought that, thanks to this double heritage, Wolf-Ferrari was the ideal composer to introduce to the American audience and music critics. In doing so, the general manager could have pursued his project of increasing the number of Italian composers whose works were staged at the Met, without upsetting the sensitivity of those critics who were against this plan.

Gatti-Casazza’s strategy worked: even before Wolf-Ferrari’s operas were performed in the United States, the press built a narrative according to which the composer’s music brought together the best of the stylistic elements normally associated with Italy (melodic lyricism) and Germany (excellent use of counterpoint, deep knowledge of orchestration, and an uncommon ability to write for the choir). Gatti-Casazza was not the only one who bet on the success of Wolf-Ferrari: Andreas Dippel, now head of the Chicago Opera Company, beat the Italian general manager by staging, in March 1911, what would later become Wolf-Ferrari’s most famous opera—Il segreto di Susanna.

The competition that followed (the Met staged Le donne curiose, L’amore medico, and a new version of Il segreto di Susanna, while the Chicago Opera Company added I gioielli della Madonna to the already mentioned American premiere of Il segreto di Susanna) made Wolf-Ferrari one of the most popular composers in North America, even outside operatic circles. His visit to the United States in 1912, followed in great detail by the American and Italian-speaking press, further strengthened his reputation. During this visit, Wolf-Ferrari was offered countless professional opportunities that he did not want to seize, perhaps in fear of missing Italy.

From the mid-1910s Wolf-Ferrari’s fame quickly faded: one of the reasons was the anti-German climate that followed the outbreak of World War I. Wolf-Ferrari, a composer who until a few years earlier had been interviewed by the most important American newspapers and music magazines, and whose works were regularly staged by the major opera houses in the United States, was relegated to oblivion.

You have also investigated the interactions between some of the Italian musicians who worked in the United States and the fascist regime, correct?

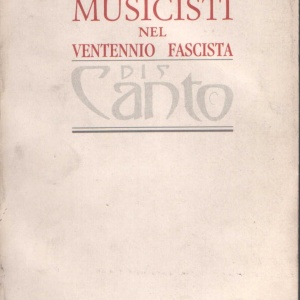

Indeed, in the course of my research I have found that a number of singers and conductors who worked for the Met, and Gatti-Casazza himself, interacted with representatives of the fascist regime. Examples include Beniamino Gigli, Giuseppe de Luca, Giacomo Lauri-Volpi, Claudia Muzio, Ettore Panizza, Aureliano Pertile, Tullio Serafin, and Ottorino Respighi. In Musica e musicisti nel ventennio fascista, published in 1984, Fiamma Nicolodi brought to light hundreds of documents on the relationships between Italian musicians and Mussolini.

With my research, I broadened the horizons opened at the time by Professor Nicolodi, showing how the musicians listed above sympathized with Mussolini as well. One can object that the musicians needed the appropriate documents to travel abroad, and that in order to obtain a passport, one had to at least show some support for the regime and the dictator himself. Nonetheless, in some cases the tone of the letters and telegrams was of sincere enthusiasm. Sometimes artists proclaimed themselves ambassadors of Italian culture abroad, at a time when being a good Italian meant, in the rhetoric of the regime, being a good fascist.

In this regard, was there a plan to make use of Italian music for promoting the image of the fascist regime abroad? And did it work? Were the Italian Americans able to listen to that music?

Until approximately twenty years ago, one could count the most important monographic studies on music in Italy during the fascist period on one hand. Much has changed in the meantime, but there is still very little existing research on the reception of Italian music abroad in the years between the two world wars.

My initial research on this subject has shown that the answer to the first question is positive. Concerning opera, Gatti-Casazza wanted to strengthen the position of the Italian repertoire at the Met, focusing in particular on living composers. The United States’ entry into war with Germany, which led to the ban against Richard Wagner’s works at the Met, made Gatti-Casazza’s plan easier. The general manager partially compensated the void left by Wagner’s operas by increasing the number of programmed works written in recent years by living Italian composers. These include Madonna Imperia by Franco Alfano, La cena delle beffe by Umberto Giordano, Le preziose ridicole by Felice Lattuada, La notte di Zoraima by Italo Montemezzi, Fra’ Gherardo by Ildebrando Pizzetti, La campana sommersa by Ottorino Respighi, I compagnacci by Primo Riccitelli, Anima allegra by Franco Vittadini and, of course, Turandot by Giacomo Puccini. The American public (and the Italian immigrants who attended the performances at the Met) had many opportunities to appreciate the operas written in Italy in the 1920s and 30s.

The same can be said of the Italian instrumental music, introduced in the United States by composers, musicians, and conductors such as Alfredo Casella, Ottorino Respighi, and Bernardino Molinari (just to mention a few), that received much attention from critics and audiences alike. In America, before World War I, “Italian music” meant above all bel canto and verismo opera, as well as Giuseppe Verdi’s works. From the early 1920s, thanks to the tours undertaken by the musicians mentioned above, orchestras in the United States began performing works by contemporary Italian composers with increasing frequency. Numerous sources attest to Italian immigrants’ enthusiastic presence at these performances.

From the regime’s viewpoint, the performance of new Italian instrumental works in the United States was an excellent opportunity to demonstrate that the concept of a “new” fascist Italy, at least in the field of music, was not only a slogan, but a reality. Italian composers were now writing successful chamber, orchestral, symphonic, and concert pieces - not only opera.

We the Italians is collaborating with the Univerde Foundation to support the candidacy of “Il Belcanto e l’Opera Lirica Italiana” for UNESCO recognition as an intangible cultural heritage of humanity. What is your opinion on the matter?

This is an exceptionally meritorious initiative for more than one reason. First of all, it is right and necessary to recognize the oral and immaterial heritage of mankind to be as important as, for example, the natural landscapes or the architectural heritage. Although this principle has only been established relatively recently, musical repertoires from all over the world have already been added to the list, and Italian opera would be an excellent candidate.

This art form, moreover, is a unique tool we can use to promote and disseminate the Italian language and culture, as well as a means to foster mutual understanding among different peoples. Singers, conductors, orchestras, and set designers from a large variety of cultures participate in opera performances, and this diversity is even clearer in the audiences that attend opera. UNESCO is an institution created to promote universal values such as peace and cultural cooperation: Italian opera is an art form that definitely promotes these values.

You may be interested

-

“The Hill” St. Louis’ Little Italy

When the fire hydrants begin to look like Italian flags with green, red and white stripes,...

-

An Unlikely Union: The love-hate story of Ne...

Award-winning author and Brooklynite Paul Moses is back with a historic yet dazzling sto...

-

Cathedral of St. John the Divine, Oratorio S...

For the first time ever, The Cathedral of St. John the Divine, in collaboration with the O...

-

Davide Gambino è il miglior "Young Italian F...

Si intitola Pietra Pesante, ed è il miglior giovane documentario italiano, a detta della N...

-

Frank Sinatra 100th Anniversary Celebration

Hoboken’s favorite son, Frank Sinatra, continues to evoke images of the good life nearly 1...

-

Garibaldi-Meucci Museum to Celebrate Ezio Pi...

On Sunday, November 17 at 2 p.m., Nick Dowen will present an hour-long program on the life...

-

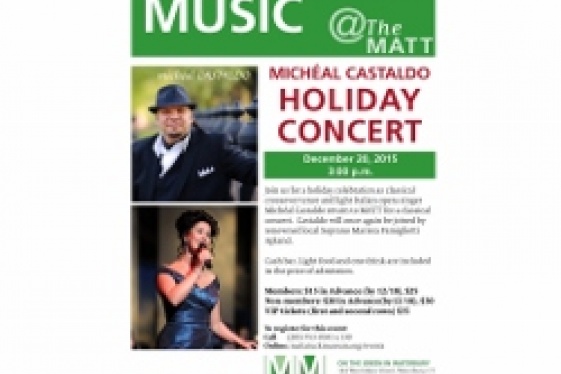

Holiday Concert with Micheal Castaldo and Ma...

The Mattatuck Museum (144 West Main St. Waterbury, CT 06702) is pleased to celebrate...

-

Italian Guitarist Roberto Fabbri to Perform...

For the final performance of his spring solo tour, Italian classical guitarist Roberto Fab...