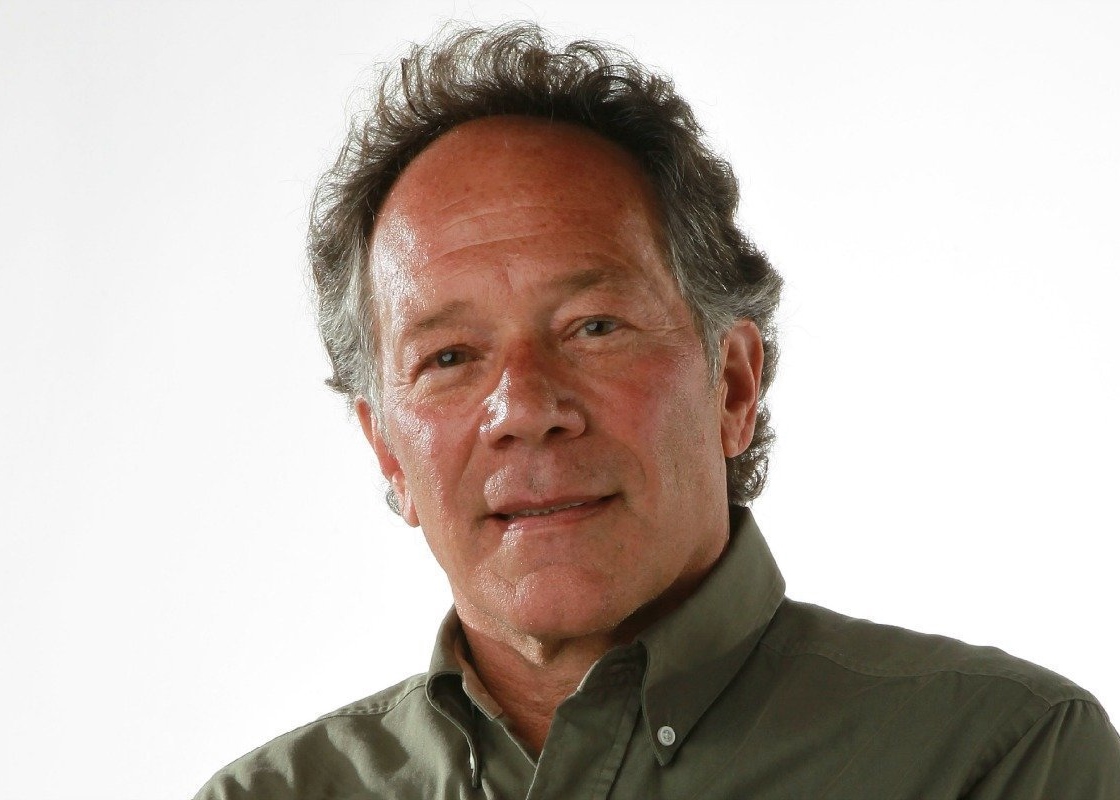

Marco LiMandri (Chief Executive Administrator of the Little Italy Association of San Diego)

Città Italia: il futuro delle Little Italy

There are still many Little Italys in the United States. Some of them are just a few blocks now, other are what's left of the urbanization that brought large roads in the middle of many American cities after the war, several times crashing an Italian community. Every one of them is a place where a big Italian heart has been, is and hopefully always will be representing the beautiful relation with the motherland.

There's one Little Italy that looks toward the future more than others. An example for its city, San Diego; its State, California; and for the whole United States. San Diego's Little Italy is something completely different. The man who more than any others we owe this vision, this pragmatic success, this tribute to Italy, is Marco LiMandri. We the Italians is very, very proud and thankful to be able to have him as our guest.

San Diego's Little Italy is maybe the most successful example of why a Little Italy is still relevant in XXI century. Please, Marco, describe to our readers why that is, and what's different in this particularly beautiful Italian neighborhood

I always say that there are three or maybe four things that are critical to build any neighborhood or business district anywhere in the world today.

The first is that you need to have an identifiable “place”. It has to be a place that people know of, or you have to create something new in an emerging area, but it has to be a known location. One of the best example is if you go to Rome or to Florence, you can see some of the central piazzas. The piazzas are a great example of a place that I am referring to. We have always had a place like this in San Diego, and it was our Little Italy: in the latter half of the 20th century, it had gone through a lot of trials and tribulations, but it was still a place.

The second thing you need is independent sustainable funding. You might have a great place, but you might not have funding to improve it. In the 1990s, we were able to create a sustainable system of funding through a series of laws and ordinances of the City of San Diego. We formed a Community Benefit District where all property owners within a district boundary in Little Italy were assessed and paid into the improvement district—giving this mechanism, adopted through a local ordinance, the funding we needed. Any municipality or government needs funding to operate. Our Little Italy needs funding to operate but it’s outside the realm of the public funds of the local government.

The third element is to have an entrepreneurial district management corporation. In this country, we have something called charitable corporations, public-benefit corporations, they serve like the NGOs that exist in Europe, in Italy too: if people donate to them, they will get a charitable tax deduction. So in 1996, we created the Little Italy Association of San Diego, a 501(c)(3) public benefit corporation to oversee and expedite the revitalization and beautification of our Little Italy neighborhood. We were funded by our base improvement district funds, that let us start out at a quarter million dollars in 1999-2000. In 2017 we had about three and a half million dollars, because our base funding had risen from what people pay in property and business assessments; we also get some funds from our parking meter revenues from visitors that come to Little Italy. So we raised 1.5 million with our activities.

We now have the place, the independent stable funding, and an entrepreneurial district management corporation. My company, New City America, is the one that initiated this process 20 years ago and currently manages the Little Italy Association of San Diego. New City America is a private corporation that is hired by the non-profit corporations to oversee all elements of Little Italy. For the last 20 years, I have visited many Little Italys all over the U.S. and a lot of other business districts to figure out what they are doing right, what they are doing wrong and take that knowledge and apply it in San Diego’s Little Italy. From my travels to Europe and particularly to Italy, I was able to see what they have done and then apply those examples here. When cities in Italy were planned, they were all built around piazzas and we took that idea because in the old days, a lot of cities in the United States were built around town squares, and public squares, but in California not so much, because California is much younger.

So we took that idea and we recreated a town center in Little Italy which everybody loves. There are about 3 million people that live in the greater San Diego area and many thousands really enjoy Little Italy, but they don’t know why. And the reason is because we rebuilt it on an old city model. We have numerous outdoor spaces, a number of piazzas - people just come here, sit down, and enjoy watching people, eating or doing whatever. It is a very public oriented area.

You have the place, the funding, and the district management corporations, but then you need politics and timing. And I know that Italy is going through tremendous political changes at this point. The politics have to be right and timing has to be right, so we were just very fortunate that the time and the politics were right in San Diego when we started our work in Little Italy. You need that element too in addition to the first three—the politics and the time are critical.

You are the Chief Executive Administrator of the Little Italy Association of San Diego, which is definitely part of the reason of this success. What does this Association do and mean for the growth of the neighborhood?

The Association in a lot of ways, is almost like a mini municipal government. We empty out the trashcans, sweep the sidewalks, trim the trees, put Christmas decorations up, have a very successful weekly Mercato or Farmers Market, light the Christmas trees, run different events, produce a website, operate social media, manage parking and run a valet program, deal with the homeless issues and security, built a dog park and more. So, we take the finances and basically operate Little Italy in many ways like a city government would run a small town or like a mall company would run a mall. We have 48 square blocks and we do everything to make sure that the people within all those 48 square blocks feel like there is a sense of order, beautification and a dynamic community.

For example, we have 22 maintenance and landscaping employees and 18 valet employees. They work every day to manage Little Italy and to me it’s a model that Italy has to go towards, because your municipal governments are so stretched in terms of revenues at this point. There’s a need of a partnership between the government and the NGOs in Italy, so that NGOs can do things that the municipal governments don’t have the money to do anymore.

For example, two years ago I visited Naples and we were looking at these magnificent buildings and your center city, but then I look at the parks and they are dirty, there’s litter all over the place. The city doesn’t have the funds to keep it up, but I would say an NGO should be doing it, based upon the revenue that they generate within that area. So let’s say if there’s a hotel, maybe that hotel charges a little bit more for staying there, the money stays in the area, and allows people to clean up that district surrounding the hotel. So it’s a question of creating the revenue sources managed by the NGOs, which will make that place a clean, dynamic and attractive for tourists, visitors and employees and most importantly, its citizens.

To keep this model running, you have to have flexible laws in place. There is money in the neighborhoods, there’s money in the business districts. Take the Spanish Steps in Rome, for example: should the Roman government clean the Spanish Steps? No, all the businesses and hotels around the Spanish Steps should be the ones who provide the funds to clean and maintain it, because they benefit from their proximity to the Spanish Steps. And they’ll relieve the burden from the Roman government by doing that. This is the way we need to operate our cities in the XXIst century. We cannot rely on the municipal of government as we did in the 20th century due to strained revenue sources, we need to be able to generate money from the community, and then use them in the place they were generated.

The Association also gives an annual "State of the Neighborhood," just like the annual State of the Nation given by POTUS …

Yes, I do that. We're about to open the new Piazza della Famiglia, a 10,000 square foot public space. In a year, people who move to Little Italy, will say “Oh, the piazza has always been there.” But, no, it hasn’t! This yearly meeting is where we will say, “see this is what it looked like before.” We are constantly teaching people that things have not always been like this. There used to be a full block parking lot, now a high rise building housing hundreds of people.

I show people these before and after photos every year: “This is the way it was, this is the way it is.” And the more people move here and the more people visit here, it creates more issues, more litter, more problems to solve, but also more opportunities. More trees are growing: we’ve never had an urban forest before, we now have 1,000 trees in Little Italy and we maintain them. So it’s important that every year they see what we have been able to do to change and improve our Little Italy, and the Annual Dinner puts it all into perspective.

You are also the President of New City America. Please tell us something about what you do, and if your expertise could help other cities in reviving their Little Italy or, why not, create a brand new one.

New City America is a family owned company that deals with the issues I previously mentioned. We identify a place, we create a financing mechanism, and then a non-profit corporations that will use those funds to improve the place. There are laws throughout the United States that allow people to do this, so I am a consultant to these other cities. We’ve created a system of assessment districts or financial mechanisms in 78 different locations nationwide. Probably more than any other company in the country over the last 20 years.

We’ve always used our Little Italy as the model to show how we can make dramatic changes within 10, 15 or 20 years, and what's the progression of it is. The company is owned by my wife and I, our three sons work for the company and we work all over the country in creating this model of independent financing run by non-profit corporations. Then we train people to figure out how to make improvements as quickly as possible. To me it’s an international model that can be applied anywhere.

I believe this movement recently called “placemaking” is an international model. I look at cities all throughout the world. If you are in Rome, or in Naples, or in Florence, the cities normally provide what I would call “curb-to-curb” services, or they deal with the streets. The curb is where the sidewalk ends and the street begins. Cities normally provide curb-to-curb services but they don’t work curb-to-property line. And curb-to-property line normally is the sidewalks. So the cities normally don’t deal with the sidewalks, but that’s what people use. People don’t walk in the streets, they walk on the sidewalks. So how’s their experience when they walk on the sidewalks. Is it clean? Is it attractive? Does it smell? Are people trying to steal from them? We try to manage the experience people have on the sidewalks.

If you walk out in a street in Rome, from building to building across the street, all of that area is public space, but most of that public space is dedicated to cars or vehicles. That’s what streets are, they are public spaces dedicated to mechanized transportation. We try to deal with the public spaces that are designed to the pedestrians and that’s what gives people a great pedestrian experience. But again, are there foul odors, is there graffiti along the walls, are the sidewalks filthy or have tripping hazards? Are trees dead? So how do we make those sidewalks as attractive as possible? And then, how do we actually try to expand those sidewalks to all the public spaces that are not dedicated to cars but are dedicated to people? I see that a few cities are doing it in Italy, by closing down spaces to cars and only letting people walk there. That’s the model we are using here and it’s working really well. As a famous planner on Lincoln Road in South Beach Miami Florida once said “a car never purchased anything.”

Is there any other Little Italy in the US you will maybe work with and apply the same model in the future?

I’ve been to Mulberry Street in New York City many, many times and I worked with them. The Manhattan Little Italy is the “mother of all Little Italys in the US.” But unfortunately, the businesses are not looking to tell the story of Italian immigrants, as they should be. If you come to our Little Italy, you can see public art and plaques that tell the stories of our Little Italy. We were the tuna capital of the world until the 1970s. On Mulberry Street, the neighborhood is primarily driven by business owners who are trying to increase the amount of people coming in and eating at their restaurants, but is not conducive towards educating the public of the incredibly rich history that arose from the Italian Americans who came from that community.

I think it’s so well done in Italy, people walk slower because they see many different things. What they do on the New York City sidewalks is walk fast, because they are trying to get to their places. We want to slow them down. There are two major Little Italys in New York City: one on Mulberry Street in Manhattan and the other in The Bronx on Arthur Avenue. In the Bronx they have the place, they have a lean funding mechanism, but they have not had, up to this point, an entrepreneurial management corporation. But all of that can be fixed with the proper leadership. Only San Diego and the Bronx Little Italy currently have the three elements to rapidly improve their Little Italys.

Probably the finest Little Italy outside San Diego is in Boston, and it’s called North End. Very popular, very active, but there is no independent financing to improve the neighborhood and no public corporation of business owners or property owners. So it’s literally always in a state of change and disorganization. There’s no great central public spaces, except across the street on the Rose Kennedy Greenway. It does not have systematic sidewalk cleaning services, there is no management of parking. It has a wonderful brand, but it’s not managed well. But I will say that’s the next best Little Italy.

You know who has a very neat Little Italy, but they also don’t have a funding mechanism? Providence, Rhode Island. They have the best Italian markets in the country, there’s a central piazza, but it’s not well maintained, and I think if they were to take the model we have been using, in terms of the funding mechanism and the management corporations, they would be far more attractive to a lot of business and visitors. They don’t have a website, for example: if you look at our Little Italy website, it is extensive. The Little Italy San Diego website has a lot of history of our Little Italy, how we do things, new initiatives, etc. They don’t have that in the North End, they don’t have that really in Mulberry Street, New York City, and not really in Providence either.

They used to have a great Little Italy in Philadelphia, it’s not so much there anymore. The similar situation exists in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Chicago’s Little Italy is called Taylor Street and I did a lot of work there. Again, they could not put together the finance mechanism or have the corporation to run the district, so that’s slowly dwindling, even though I would love to continue to work in Chicago.

North Beach in San Francisco, the historic Italian American community, considers itself to be the place where the Beatniks generation began. I worked there for 10 years, and my son runs a small district in North Beach, but it’s not an Italian business district. The owner of one of the oldest Italian restaurants in San Francisco, Tommaso’s, is on our Board and the restaurant is owned by wonderful people: but as we go up Columbus Avenue, a lot of business owners are not interested in collaborating or rebuilding their Italian district.

Los Angeles lost its Little Italy in the 1930s. This one city Councilman, a gentleman, Joe Buscaino, represents San Pedro on the water in Los Angeles. Joe has just hired me to work with him to try to create a Little Italy in their current Downtown San Pedro that has an historic Italian core. That would be the only Little Italy on the West Coast besides San Diego. Joe has been to San Diego, and loves what we have done here. San Pedro was also a sister city with San Diego in the fishing and tuna industry and they had the canning factories there and it worked out really well for the immigrant families. There’s just so many things that can happen in San Pedro and Joe is such a great advocate. I think this has a lot of potential.

Baltimore has got a great Little Italy, but it’s very small: it’s where Nancy Pelosi is from. Her father was the mayor in Baltimore in the 50s and 60s and she came from the D’Alessandro family who had great political roots in Baltimore. It’s not really a business district per se, it is just integrated into the community.

I also have been working with gentlemen from Rochester, New York, to create and bring back Little Italy on Lyell Avenue, in Rochester. The only Little Italy I haven’t been to is in New Haven, Connecticut. I understand they have a small and attractive Little Italy. We are looking into creating an alliance of Little Italys in America.

How's Made in Italy doing in the San Diego concept, and particularly in Little Italy? Is there room for improvement?

One of the most surprising and rewarding achievements that we’ve made is that we have attracted 18 - 20 Italian immigrant entrepreneurs, who didn’t believe that they could make a decent living in Italy and recently came over here and opened wonderful restaurants. Young entrepreneurs from Italy have skipped New York City, Chicago, San Francisco, and other major cities to come to San Diego’s Little Italy. And now, they are part of the fabric of this community, they come from all different places in Italy and they bring all of their experiences, language, recipes and families. We have a video on our website where we interview these recent immigrants in Italian and they explain why they came to San Diego’s Little Italy. That is one of our greatest achievements, because we know we have become the conduit for Italians coming to the United States, and they’re entrepreneurs - they can make a good living, create jobs, make money, and raise their families here in San Diego, where the climate is very Mediterranean-like.

Another thing that I think we have done more effectively than in any other Little Italys in the country is developing new piazzas. We started out with Piazza Basilone, which is dedicated to the war hero John Basilone, who was the most decorated Italian American in U.S. history. We opened Piazza Basilone in 2002, and people are in love with it, the marines love going to it. We have hosted wounded warriors for the international Special Olympics at Camp Pendleton there. Countries from all over the world come to Camp Pendleton in San Diego County for the annual Wounded Warrior games, and they always come to Piazza Basilone every year. There’s over a hundred soldiers who attend each year, and our restaurants open up themselves to the athletes who eat there, get their beer, wine whatever they like. Piazza Basilone was the first Piazza we built and then we opened the second one called Piazza Pescatore, which is dedicated to the fishermen.

We are about to open up Piazza della Famiglia which is a 10,000 square-foot public space. It’s a full city block, which will be closed down to traffic and it’s going to be our town center. That will open up very soon, in 2018. After that we will open up Piazza Giannini, named after Amedeo Giannini, a gentlemen who created Bank of Italy, later named the Bank of America. We create our piazzas based upon famous Italians or Italian Americans. In every piazza we have tables and chairs, we usually have a plaque which tells the story of the piazza. We have a statue, just like when you go to Villa Borghese in Rome, you see all the busts and pedestals of all the famous Italians throughout history. Every piazza has its own bust and pedestal which explains who those people were and why we named a piazza after them. So eventually, the goal is to have completed close to 10 piazzas all throughout Little Italy. We know that people eventually will come here just to see the piazzas.

Once upon a time, all over the country a Little Italy was a place with many hardworking Italians with big hearts, poor living conditions, few bucks, and homesickness. If a new kind of Little Italy would be possible today, how would you describe it?

When I was working with the people on Mulberry Street in Manhattan around 10 years ago, I told them that Little Italy is a term that we used in the XXth century. In the XXIst century we should really be looking at a model like Città Italia, “the Italian city.” This means that in the XXIst century, the model is about a place where Italian immigrants come and live, Italian businesses/restaurants are located, senior citizens or Italian Americans move to that neighborhood. It becomes a walkable community, with great public spaces, with really energizing entrepreneurs, it tells the story of Italian Americans and immigrants and is based upon the entrepreneurial and cultural contributions that Italians have made in to the United States. You can do that in every single city, but it shouldn’t be about pizza, spaghetti and meatballs, it should really be about the totality of the Italian culture, and that’s why I call it Città Italia, because it’s really the model of the XXIst century Italian neighborhood.

Italians who live in the US should have a place where they can go, whether they are in New York City, Rochester, Chicago, San Diego, Los Angeles. They should have enclaves where they can speak the native language and they can bring their skills whether they are scientists, teachers, young individuals or entrepreneurs who work in high-tech, or restaurateurs; or they have families and just want their children to be in an Italian environment. That is, I think, the model of the XXIst century, how we keep the best of Italy and apply it in certain districts in the American cities, and that’s where the concept of the Città Italia can flourish.

There aren’t Little Irelands, Little Englands, Little Frances, but there are Little Italys. But the model that was existing in the XXth century will not exist in the XXIst century. We need to completely change who we are and look much more towards public spaces, public art, and education about the contributions the Italians have made in the United States and throughout the world. I always say, people who walk on the street should learn about that street and the people it created.

It makes sense, it would mirror the evolution of the Italian American community through the decades…

That's right. I know from doing this for a living, people are happy if they are making a good living for their families, living in a safe community, and walking with their neighbors to get a cappuccino or just something to eat, and if there’s a central Catholic church and nice public spaces and parks. That’s what makes people happy. To achieve that, you have to set a goal, on a specific timeline, get it done, then we move to the next project.

We can do this with Little Italys all over the U.S., using our business model: or we can even take what we do in San Diego and use it as a model in the Italian cities. That’s what we need to do. The world is changing so rapidly and radically, we all can use good, humane models of the way we should live in the coming decades. Our concept of Città Italia could be one of the answers.

You may be interested

-

“The Art of Bulgari: La Dolce Vita & Beyond,...

by Matthew Breen Fashion fans will be in for a treat this fall when the Fine Arts Museums...

-

“The Hill” St. Louis’ Little Italy

When the fire hydrants begin to look like Italian flags with green, red and white stripes,...

-

13th Annual Galbani Italian Feast of San Gen...

In September of 2002, some of Los Angeles' most prominent Italian American citizens got to...

-

1st Annual Little Italy Cannoli Tournament

Little Italy San Jose will be hosting a single elimination Cannoli tournament to coincide...

-

2015 scholarship competition

The La Famiglia Scholarship committee is pleased to announce the financial aid competition...

-

30th Annual Art Holiday Walk, Winter Winter...

Holiday walk hours Friday, 12/5 noon-9pm, Saturday ,12/6 noon-9pm Sunday, 12/7 noon-6pm. S...

-

9th Annual Sacco and Vanzetti March/Rally

Saturday, August 23rd, in Boston, the 87th anniversary of the execution of Nicola Sacco an...

-

A Week in Emilia Romagna: An Italian Atmosp...

The Wine Consortium of Romagna, together with Consulate General of Italy in Boston, the Ho...