Since 2006, Fondazione Migrantes has published a yearly report on Italian citizens in the world – a unique resource for those with an interest in migration. We ask the project’s chief editor Delfina Licata to tell us more about it.

Delfina – how did the idea of the report come about?

The idea first came about in 2006. For 25 years, Fondazione Migrantes published a book – “Rapporto Immigrazione” – in collaboration with Caritas on the presence of immigrants in Italy, and we decided to retrace our own history of migration. Italian citizens still migrate today, with different motivations and in varying numbers. The publication starts from the past but brings the arguments up to date and analyses the present day. The contributors from different professional fields – historians, sociologists, economists, architects, artists – write from Italy or from abroad.

What are the numbers of Italian migration and presence in the USA?

Of the almost 26 million Italians who left Italy between 1876 and 1976 to make their fortune abroad, 22% went to the USA. Between 1892 and 1924, over 20 million people crossed Ellis Island: between 1896 and 1917, and then again in 1920-21, the Italians were the most numerous. In 1910, New York – the first city in the US in terms of number of inhabitants – counted 4.766.883 residents: 40% of these were foreigners and amongst them were 340.795 Italians. Of the 5 million 300 thousand Italians that migrated to the USA between 1820 and 1978, over 2 million did so between 1900 and 1910, and almost 4 million between 1880 and 1915 (between 50 and 60% of these returned to Italy in the first 15 years of the century).

Who were the Italians migrating to America?

Until 1900, the majority of them came from the North of Italy (mostly Veneto, Friuli-Venezia Giulia and Piedmont), but after that the bulk of them was made up of southerners, mostly from Campania, Sicily and Calabria.

Several of them were farmers destined to work in the mines. American law allowed them to bring along helpers with whom they could share their salary, so many miners brought their 8-12 year old sons to work with them, often illegally. People from Lombardy mostly went to work as miners and manual laborers in Missouri, Illinois, Vermont, Michigan, Washington State and later in Iowa, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and San Francisco. There were also many political exiles from Piedmont, Lombardy and Tuscany who participated in the gold rush along the Sierra Nevada. They were the founders of several of the existing ghost towns, named after heroes of the Italian Risorgimento.

Between 1901 and 1913, over 500.000 people emigrated from Calabria: among them were political and trade union managers who became the leaders of the American workers’ movement in the big cities and were thus filed as “dangerous subversives”.

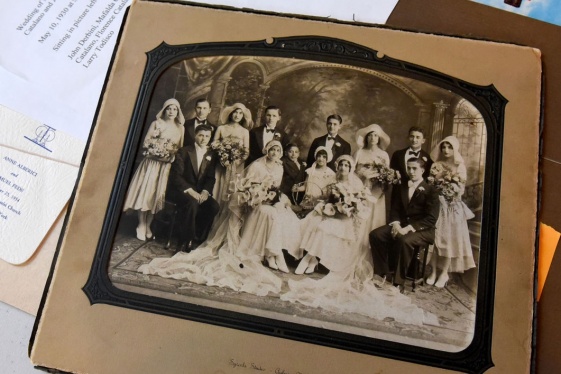

As well as miners, in the early days the Italian immigrants were mainly farmers and artisans. Many of them were illiterate and itinerant, and would end up taking on the most diverse jobs and “building” America through its roads and skyscrapers. They often got caught up in the racketeering networks. There were numerous examples of family reunifications and families formed or growing on American soil, giving birth to the second generation. This generation and the following ones were often more educated, and leading personalities in the social, political, and entrepreneurial fields came out of them.

The protagonists of the most recent migrations on the other hand are often university students, postgraduates and young professionals working in the American offices of Italian companies.

The Church’s role in helping Italians in the US was fundamental…

Since the beginning, priests and men of religion (Scalabrinian missionaries, Franciscan, Silesian, Jesuits and others) followed and assisted the Italian migrants. Monsignor Scalabrini in particular was active in favor of Italian migrants in the States to defend them from the exploitation of migration agents and other intermediaries and to offer them the comfort of the Church.

Profession of the Catholic Church in the USA was difficult because this was opposed not only by the Protestants, but also by the local Catholics, who did not tolerate the popular Mediterranean interpretation of the religion and often considered patron saint festivals as pagan or superficial events. In New York in the nineteenth century, Italian immigrants – considered inadequate for the local churches – were allowed to congregate in basements. Many of them refused to accept this arrangement and chose to convert to the Protestant confession: in 1918 these were 25.000 in New York alone.

How did the Americans respond to the arrival of large numbers of Italian migrants?

Very rarely did our fellow countrymen see their American dream materialize. In most cases they ended up doing the most humble jobs. Between the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries, Italian migrants were the object of defamation campaigns that represented them as being anthropologically inclined to committing crime. The prejudice was mainly associated with southerners who were called by the names such as “dago” and “wop”.

This mounting racism escalated into violence. In New Orleans, Italian migrants had substituted the black slaves in the cotton harvest: at the end of the 1800s there were around 30.000 in New Orleans, 90% of them were Sicilian. Some of them were accused of murdering the city’s chief of police, and the mayor gave orders to search the entire Italian community. 250 people were arrested, and 11 of these were tried for a crime they had not committed. But because they were innocent, they were eventually acquitted. This caused the anger of the locals, who were waiting for an excuse to turn against the Italian community. The day after – on March 14 1891, an enraged crowd of 20.000 people rushed the jail, took the 11 Italians and slaughtered them savagely. A moment of tension between the two governments ensued, terminating with the official disapproval of the events on the part of President Harrison and compensation of the victims’ families.

In 1913, in Calumet, Michigan, the Italian migrants working in the copper mines went on strike because they hadn’t received their pay for several months. That Christmas evening the Italian community gathered in the premises of the Società Italiana di Mutua Beneficenza, known as Italian Hall. Some men sent by the copper industrialist Charles Moyer bolted the doors shouting “Fire! Fire!”. 73 people – most of them children – died in the commotion.

Nella descrizione dei rapporti tra Italia e Usa l'emigrazione italiana ha un ruolo fondamentale. La Fondazione Migrantes pubblica dal 2006 il rapporto annuale sugli Italiani nel mondo, insostituibile punto di riferimento per chi si occupa di questo tema. Abbiamo chiesto alla redattrice capo del progetto, Delfina Licata, di parlarcene.

Come è nata l'idea?

L'idea è nata nel 2006: da 15 anni insieme alla Caritas realizzavamo un volume sulla presenza degli immigrati in Italia, e si decise di far presa sulle coscienze ricordando il nostro passato emigratorio. La nostra idea di emigrazione italiana legata al passato è diversa dalla realtà dei fatti. Gli italiani continuano a lasciare l'Italia oggi con motivazioni e numeri diversi: il volume parte dal passato ma attualizza gli argomenti e arriva all'oggi, grazie a redattori dalle diverse professionalità – storici, sociologi, economisti, architetti, artisti – che scrivono dall'Italia e dall'estero.

Quali numeri hanno contraddistinto l'emigrazione e la presenza italiana negli Usa?

Dei quasi 26 milioni di connazionali che dal 1876 al 1976 hanno lasciato l'Italia in cerca di fortuna all'estero, il 22% ha raggiunto gli Usa. Dal 1892 al 1924 per Ellis Island passarono più di 20 milioni di persone da tutto il mondo: dal 1896 al 1917 e poi nel 1920-21 gli italiani furono i più numerosi. Nel 1910 New York, prima città negli Stati Uniti per numero di abitanti e seconda al mondo dopo Londra, ospitava 4.766.883 residenti, di cui il 40% composto da stranieri tra i quali i più numerosi erano gli ebrei dell'Est Europa, poi gli italiani (340.795) e poi tedeschi e irlandesi. È questo il periodo del grande esodo italiano verso gli States: dei 5 milioni e 300 mila connazionali che tra il 1820 e il 1978 vi emigrano, più di 2 milioni lo fanno tra il 1900 e 1910, quasi 4 milioni tra il 1880 e il 1915 (il 50/60% dei quali poi rientrò in Italia nei primi 15 anni del secolo).

Chi erano questi italiani che emigravano in America?

Fino al 1900 la maggior parte di essi proveniva dal Nord Italia (soprattutto Veneto, Friuli Venezia Giulia e Piemonte) ma il grosso è stato poi costituito da meridionali, soprattutto campani, siciliani e calabresi. Diversi erano contadini destinati a lavorare nelle miniere: la legge americana consentiva loro di portarsi aiutanti con cui dividere il salario e molti minatori chiamarono a lavorare i loro figli di 8-12 anni, spesso clandestini. I lombardi venivano soprattutto per lavorare come minatori e manovali nel Missouri, nell'Illinois, nel Vermont, nel Michigan, nello Stato di Washington e poi in Iowa, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona e a San Francisco. Numerosi furono gli esuli politici piemontesi, lombardi e toscani che, dopo la Prima Guerra d'Indipendenza, parteciparono alla corsa all'oro lungo la Sierra Nevada, fondando diverse delle attuali ghost town intitolate a eroi del Risorgimento italiano. Dalla Calabria, tra il 1901 e il 1913 emigrarono più di 500.000 persone: tra di essi anche quadri politici e sindacali, che nelle grandi città diventarono protagonisti del movimento operaio statunitense e per questo schedati come "pericolosi sovversivi".

Nel 2000 circa 15,7 milioni di americani si sono dichiarati di origine italiana, + 7% rispetto al 1990: di questi il 57% vive nel Nord Est (700.000 nella sola Manhattan, il gruppo europeo più numeroso), il 14% nell'Ovest, il 16% nel Centro-Nord e il restante 13% nel Sud. La comunità italiana più numerosa è nello Stato di New York: nel 2000 c'erano 1.277.411 persone, 676.794 uomini e 600.617 donne, in età lavorativa (almeno 16 anni). Il 37,5 % di questi erano direttori, manager e liberi professionisti. Nell'ambito dei servizi operava il 14% del totale, con prevalenza nel settore alimentare. I settori della vendita, degli impieghi amministrativi, delle costruzioni e della manutenzione ne coinvolgevano poco più del 30%, mentre il 9,4 % era nei settori della produzione e dei trasporti. E' dunque oggi una comunità dalle categorie professionali medio-alte, radicata tanto in ambiti innovativi (finanziario, tecnologico, informatico), che in settori più tradizionali (preparazione alimentare, commercio al dettaglio, trasporti).

Tuttavia, all'inizio gli italiani erano soprattutto agricoltori e artigiani, molti analfabeti e ambulanti, che si trovarono a svolgere le professioni più diverse e a "costruire" l'America edificando strade e grattacieli e finendo spesso nelle maglie della malavita. Numerosi furono i ricongiungimenti familiari e i nuclei che si costituirono o ampliarono in terra americana dando vita alla seconda generazione. Quest'ultima e poi quelle successive videro una più accentuata acculturazione; crebbero personalità di spicco a livello sociale, politico, imprenditoriale. Si pensi ai poliziotti, agli attori, ai politici fino ad arrivare ad oggi quando l'Italia è sinonimo di moda ed eccellenza, la nostra lingua gode di grande popolarità e la società americana è sempre più attratta - per interesse, piacere o affari - dai rapporti con l'Italia. Le migrazioni più recenti hanno tra i loro protagonisti sia studenti universitari e post-universitari che giovani professionisti operanti per conto di filiali americane di aziende italiane.

La Chiesa ha avuto un ruolo fondamentale nell'aiutare i nostri connazionali. Ci può accennare qualcosa a questo proposito?

Fin dall'inizio, sacerdoti e religiosi (scalabriniani, francescani, salesiani, gesuiti ed altri) seguirono ed assistettero i migranti italiani. Mons. Scalabrini, in particolare, fondò la Congregazione dei Missionari di S. Carlo nel 1887 e, nel 1889, la Società San Raffaele composta interamente da laici. Egli si attivò concretamente in favore degli emigranti transoceanici per difenderli dagli sfruttamenti degli agenti d'emigrazione e di altri intermediari e per offrire loro il conforto della chiesa. La testimonianza della fede cattolica negli USA fu difficile perché avversata non solo dai protestanti ma anche dai cattolici del posto, impazienti nei confronti della religiosità popolare mediterranea e propensi a considerare pagane o superficiali le feste patronali. A New York nel XIX secolo gli italiani, non considerati adeguati a frequentare le chiese locali, furono autorizzati a riunirsi negli scantinati. Molti di loro, non accettando questa collocazione, scelsero la confessione protestante: nel 1918 nella sola New York furono 25.000.

Quale fu la risposta americana all'arrivo di questo grande numero di italiani?

Ben di rado i nostri connazionali che emigravano negli Stati Uniti videro realizzato l'American Dream: finirono con lo svolgere i lavori più umili come spazzini, operai, scaricatori portuali, minatori, fruttivendoli. Fra di essi c'erano anche molti volontari dell'esercito di Garibaldi. A cavallo tra i due secoli, gli emigranti italiani furono oggetto di campagne diffamatorie venendo rappresentati come antropologicamente portati a delinquere, una seria minaccia per l'ordine pubblico. Il pregiudizio era rivolto principalmente ai meridionali chiamati con i dispregiativi "dago" e "wop"; addirittura i siciliani furono definiti, nel 1911, not white.

Questo razzismo montante sfociò in violenza. Un efferato attacco avvenne a New Orleans nel 1891, dove molti emigranti italiani avevano sostituito gli schiavi neri nel lavoro di coltivazione e raccolta del cotone: a fine '800 a New Orleans ce n'erano circa 30.000, siciliani per il 90%. Alcuni di essi vennero accusati dell'omicidio del capo della polizia della città (probabilmente ucciso dalla mafia o da avversari politici), ed il sindaco ordinò un rastrellamento presso la comunità italiana. Vennero arrestate 250 persone, di queste 11 vennero processate per un delitto che non avevano commesso e, poiché innocenti, furono assolti in regolare giudizio: ciò provocò la collera degli autoctoni, in cerca di un pretesto per colpire gli italiani. Il giorno successivo, il 14 marzo 1891, una folla inferocita di 20.000 persone prese d'assalto la prigione, prelevò gli 11 italiani e li trucidò selvaggiamente a colpi d'arma da fuoco, impiccandoli e a bastonate. Seguì un momento di forte tensione tra i due governi, che si stemperò con la deplorazione ufficiale dell'accaduto da parte del Presidente Harrison ed un risarcimento di 25.000 $ ai familiari delle vittime.

Sempre a fine '800 in Louisiana, a Tallulah, 5 emigranti italiani furono linciati a morte perché "rei" di essere troppo gentili con i neri. Nel 1913, a Calumet in Michigan, gli emigranti italiani nelle miniere di rame scioperarono perché da mesi non percepivano la paga. Nella notte di Natale la comunità italiana si riunì presso la sede della locale Società Mutua Beneficenza Italiana, detta Italian Hall. Una festa povera: nastrini colorati, qualche torta fatta in casa, pochi cesti di frutta secca, un'orchestrina alla buona. I sicari dell'industriale del rame Charles Moyer, a capo della Western Federation of Miners, sprangarono le porte urlando "Al fuoco!". Nel parapiglia che si scatenò morirono in 73, in gran parte bambini.

Considerati da molti addirittura l'anello mancante tra uomini e scimmie, sfruttati e maltrattati, alcuni tra gli emigranti italiani entrarono nei circuiti della malavita, gettando così un indelebile marchio d'infamia sull'intera comunità. L'inizio del XX secolo segnò l'ascesa della mafia in America alla quale si oppose Joe Petrosino, il grande poliziotto italo-americano all'epoca a capo dell'Italian Legion, una squadra di poliziotti italo-americani creata proprio per contrastare l'ascesa della "Mano Nera", così chiamata perché sui muri delle case degli emigranti italiani apparivano delle impronte di mani sporche di carbone. Petrosino intuì il collegamento mafioso tra New York e la Sicilia e, proprio per questo, tornò in Italia dove, il 12 marzo 1909, fu ucciso con tre colpi di pistola nel centro di Palermo.